How Superstition Became A Throughline in My Gothic Thriller

When I wrote my latest novel, Do What Godmother Says, a gothic dual-timeline thriller, I faced a major challenge. I knew I wanted the story to take place during two time periods (in the present and in the 1920s). I wanted it to be about two different women: Essie, an aspiring Harlem Renaissance painter, and Shanice, an out-of-work writer struggling with past trauma and her mental health.

Each is going through her own perils because of a mystery surrounding a portrait that Essie painted—which Shanice inherits from her grandmother 100 years later. These mysteries unfold congruently in the novel and connect by the end.

But as I started my outline, I realized that besides the painting and the fact that they were both women and African American, there was no major throughline to the story—until the ending. I worried that it would be too jarring for readers, jumping back and forth between Essie’s and Shanice’s stories and voices. Not only would the novel lose momentum, but it would also lose atmosphere, which is a core element in the gothic genre.

I figured out that the throughline could be thematic. It would have to not only connect the two women’s stories, but also keep the otherworldly atmosphere. Another requirement was that it had to fit within both Essie’s and Shanice’s cultural backgrounds and perspectives so it wouldn’t feel awkward or shoe-horned into their stories. That throughline turned out to be superstition and its impact on one’s perception of the world.

The traumatic events in the thriller make Essie, an intellectual and cynic, a believer in the superstitions of her childhood back in rural South Carolina. Decades later, Shanice is raised on these beliefs as well thanks to her superstitious grandmother. Throughout the novel, both women make references to common African American superstitions and sayings—ones that I’ve heard most of my life.

Black-eyed Peas and Cold House Keys

Among the smorgasbord of foods on the dining room table that my mom bakes to celebrate the advent of a new year, you’ll always find a serving dish of black-eyed peas. She makes it the same way every New Year’s Day like her grandmother did decades ago, and I suspect her grandmother’s grandmother did a hundred years ago. Mom always begs everyone present to eat at least one spoonful.

“It’ll bring you good luck,” she promises.

When I was eight years old and got a nosebleed at summer camp, the camp counselors—two elderly Black women—told me to sit down immediately and pinch my nose to staunch the bleeding.

“Wait,” one said, snapping her fingers. “Anybody have car keys?”

“Why?” another one asked.

“Because you have to put cold keys down her back to help stop the bleeding.”

The other counselor scrambled to her purse to get keys.

So, there I was in my shorts and tank top, feeling ridiculous with cold, heavy house keys nestled against my bare, sweaty skin.

The superstition of eating black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day is an old Southern tradition. It was common among the enslaved in the United States, and from what I’ve read, it’s also common in the Caribbean. Black-eyed peas are a traditional staple food in West Africa that probably traveled with slaves during the Middle Passage.

I still have yet to find the origin of the “cold keys down the back can stop a nosebleed” superstition, but I saw several accounts online of other folks being told the same thing when they were younger—and they swear by its efficacy. (I don’t; my nose kept bleeding.)

African American culture is full of superstitions with no clear origins that have managed to traverse regions and generations. A ringing ear means someone is talking about you… If your palm itches, that means money is coming your way… Splitting a pole gives you bad luck… You can even see the physical remnants of these superstitions in some places: the beautiful glass bottle tree gardens in the front yards of homes in some Southern towns, especially in the Carolina low country, are meant to ward off evil spirits. It’s a tradition that originated in the Congo. The practice was brought to the states by enslaved Africans.

The Double-edged Sword of Superstition

These superstitions and traditions have endured despite the passage of time, adoption of Christianity, education, and even modern incredulity that tells us we should “know better.”

My theory for why they’ve endured is because while slavery managed to strip the enslaved of their homelands, languages, names, families, and even their personhood, it couldn’t strip them of their engrained traditions. After slavery was Jim Crow, the rise of the Klu Klux Klan, and other injustices. For the many who have and continue to endure discrimination or subjugation, superstitions can give you a sense of control or power.

“Superstitions provide people with the sense that they’ve done one more thing to try to ensure the outcome they are looking for,” said Dr. Stuart Vyse in the WebMD online article “The Psychology of Superstition: Is ‘magical’ thinking hurting or helping you?”

At one point in the novel, when Shanice expresses her frustrations with her grandmother’s superstitious nature, Gram tells her why her superstitions are so important to her.

“It’s words of wisdom given to me by my mama and her mama before her,” Gram tells her. “Words to guide you and keep you safe in this crazy world. One of the few things you can control, when you can’t control much else.”

Of course, superstitions can be a double-edged sword.

Dr. Vyse also warned in the article that “phobic (fearful) superstitions” can interfere with our lives and cause a lot of anxiety.

I had to explore that as well in the book. Shanice, who is already struggling with generalized anxiety disorder, finds her superstitions to be more of a hindrance than a help.

Personally, I appreciate the cultural significance of superstitions, but I don’t take them seriously. However, I still eat my spoonful of black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day and offer some to my daughter for the sake of tradition and out of respect to Mom and those who came before me.

—

L.S. Stratton is an NAACP Image Award-nominated author and former crime newspaper reporter who has written more than a dozen books under different pen names in just about every genre from thrillers to romance to historical fiction. She currently lives in Maryland with her husband, their daughter, and their tuxedo cat.

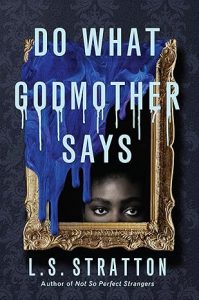

DO WHAT GODMOTHER SAYS

A modern-day writer and a Harlem Renaissance artist are connected by a painting with a deadly secret in this gripping dual-timeline gothic thriller.

A modern-day writer and a Harlem Renaissance artist are connected by a painting with a deadly secret in this gripping dual-timeline gothic thriller.

Shanice Pierce knows better than to heed bad omens. But she has a hard time ignoring the signs when she finds herself newly single and out of a job on the same seemingly cursed day.

Then, while cleaning out her grandmother’s house, Shanice comes across a painting she hasn’t seen in years. Drawn to the haunting portrait in a way she can’t explain, Shanice accepts her grandmother’s offer to keep the family heirloom.

She soon uncovers the story of the artist, a Harlem Renaissance painter named Estelle Johnson. The young woman was taken under wing by the wealthy art patron Maude Bachmann—or “Godmother” as she insisted her artists call her—and vanished shortly after Bachmann’s brutal murder a century ago.

As Shanice digs deeper, a paranoia that’s haunted her for years returns. She becomes convinced she’s being stalked, and that the deaths happening around her are connected to the staggering offer she turned down for the painting.

But the truth hiding in plain sight is even more shocking—and deadly—than Shanice could possibly have imagined . . .

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing