How Writing About the End of the World Helped Me Find Hope

Erin Swan

On April 21, 2014, I sat in the sunny window of a Brooklyn coffee shop and wrote the beginning of a story about a girl named Bea. The next day, I finished the draft. Usually, I toil and tinker, hem and haw, but this story emerged in a giddy rush. A few days before, the idea for it had struck me. During a bout of illness, I had envisioned a girl walking across a grassland, an echo of the female figure in Andrew Wyeth’s painting “Christina’s World,” which I had recently used in one of the high school classes I teach. In my vulnerable state, I saw this girl as traumatized, so shaken by what she had experienced she thought the entire world had ended, when in reality only her own world had. A few days later, I had ten pages of stilted syntax and apocalyptic images, fed to me – or so it seemed – by Bea herself.

On April 21, 2014, I sat in the sunny window of a Brooklyn coffee shop and wrote the beginning of a story about a girl named Bea. The next day, I finished the draft. Usually, I toil and tinker, hem and haw, but this story emerged in a giddy rush. A few days before, the idea for it had struck me. During a bout of illness, I had envisioned a girl walking across a grassland, an echo of the female figure in Andrew Wyeth’s painting “Christina’s World,” which I had recently used in one of the high school classes I teach. In my vulnerable state, I saw this girl as traumatized, so shaken by what she had experienced she thought the entire world had ended, when in reality only her own world had. A few days later, I had ten pages of stilted syntax and apocalyptic images, fed to me – or so it seemed – by Bea herself.

The draft done, I returned to my usual tales of realistic fiction. That winter, however, I revisited my story about Bea. There were the strangely crafted sentences, the vacant towns and grassy wastelands, the sense of urgency I had felt while writing it. There was Bea: pregnant and mute, so scarred by her past she cannot relate to the few humans she encounters. By the story’s end, she has been arrested for trespassing and sent to a psychiatric ward, where she realizes the world that she thought was gone is still very much alive.

As I re-read it, I had an idea. What if I tried to transform it into a novel? What if, halfway through this novel, Bea’s vision actually came true? What if the world actually ended? How would the characters contend with that? Would they give up? Or would they adapt to their new environment, so that the world did not so much end as simply change?

Inspired by these ideas, I began expanding Bea’s story. A psychiatrist entered her tale, along with a backstory involving abusive parents and a sequestered childhood. I gave her a son named Paul. I took that son away and put him in foster care. I considered reuniting them. I thought ahead to their future, pondering how their world would change: a deadly virus, a cataclysmic earthquake, a series of floods? I decided Paul needed his own family, perhaps a child. Anticipated missions to Mars were very much in the news then, and so I thought why not send my characters to Mars? It was my book; I could do anything I wanted.

I began focusing less on realistic fiction and more on experimenting with genres. Working with elements of science fiction and horror allowed me a creative freedom I had not before experienced. Bea’s story felt immediate and propulsive, a vehicle for expressing my feelings about the climate we were living in. Before writing each morning, I got in the habit of reading the day’s headlines. Knowing what was happening in the world both grounded me in an increasingly disturbing reality and galvanized me to imagine something different, an alternate future to the one we were creating for ourselves.

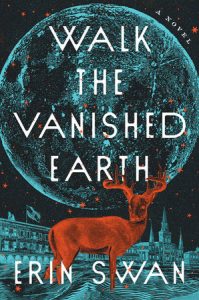

I wrote the bulk of the novel that became WALK THE VANISHED EARTH between 2016 and 2020. These were years of high tension for me. Not only did our country feel deeply unsettled on a political level, but my mother was sick. In the fall of 2016, she was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus. That winter she underwent surgery to remove the tumor. The next year, they found a tumor in her lungs, which meant another surgery. The following year, another tumor appeared; immunotherapy ensued. I did not consciously recognize it at the time, but WALK THE VANISHED EARTH became a reflection of what was happening with my mother. It is a story about mothers and their children, about trauma and its legacy. It is also a story about separation. In the novel, mothers die or walk away or get abandoned by their children. Rarely in the book do parents and children remain together. So much of writing happens on a subconscious level that it is only later we can see such patterns clearly. Recently I realized that throughout writing this novel, I was trying to find a way to say goodbye to my mother.

I did not get a chance to say goodbye, not in person. In the terrible spring of 2020, my mother died from cancer complications, alone in a Florida hospital. I was finishing my most recent draft of WALK THE VANISHED EARTH, and my agent and I had agreed it needed some hope, especially given the current situation across the globe. Two weeks after my mother’s death, I wrote a new character named Ivy. Ivy has also lost her mother, but she is uncowed. She lives in a tent settlement in western Colorado and delights in small things: poetry sung around the fire, her late mother’s antique tea set, the screen through which she contacts another girl on another planet, a girl who might be distantly related to Bea. The friendship between these two motherless girls is a hello, not a goodbye. They have learned to adapt to a constantly changing world. The earth may have vanished under their feet, but they have found a way to keep walking.

I can only wish the same for us.

—

Category: How To and Tips

In the tradition of Station Eleven, Severance and The Dog Stars, a beautifully written and emotionally stirring dystopian novel about how our dreams of the future may shift as our environment changes rapidly, even as the earth continues to spin.

In the tradition of Station Eleven, Severance and The Dog Stars, a beautifully written and emotionally stirring dystopian novel about how our dreams of the future may shift as our environment changes rapidly, even as the earth continues to spin.