Love Letters

The first letter I ever wrote to my maternal aunt Ruth, was in 1965. I don’t remember what possessed me to write to her. The risk was great and the reach was far. The letter was no doubt desperate, confessing my troubles to someone who was related, but whom I barely knew, someone I had rarely ever seen, who lived in another country—a message in a bottle.

The first letter I ever wrote to my maternal aunt Ruth, was in 1965. I don’t remember what possessed me to write to her. The risk was great and the reach was far. The letter was no doubt desperate, confessing my troubles to someone who was related, but whom I barely knew, someone I had rarely ever seen, who lived in another country—a message in a bottle.

Her quick reply contained an unexpected invitation. Within two weeks, I quit my job at a residential treatment center for disturbed kids, cashed my last paycheck, got my first passport, and bought a one-way ticket from Madison, Wisconsin to San Jose, Costa Rica.

Twenty-five years apart in age, my aunt and I could not have been more different. She was a fifty-year-old nun, living a vowed life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. I had already broken my marriage vows, and was uninterested in poverty or obedience—chastity being long since out of the question.

My aunt had been interned in a Japanese concentration camp in China when she was my age. Beyond that, I knew very little of her life, and I did not expect her to be probing or directive about mine. I was used to the women in my family who held their peace, if indeed it was peace they were holding.

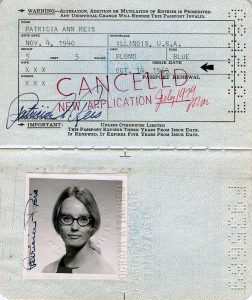

My 1965 passport picture shows a young woman with blonde hair held back in a clasp and thick lenses in her horn-rim glasses. Her face is smooth and lips full. She appears open and fresh, but internally, there is damage.

She has graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in English literature, has undergone two illegal abortions, has entered the purifiying waters of the mikvah naked and converted to Judaism, has married a history professor under the chuppah in the University Hillel Foundation chapel, and has been granted a divorce after six months under the guise of irreconcilable differences. She is not yet twenty-five. (photograph)

She has graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in English literature, has undergone two illegal abortions, has entered the purifiying waters of the mikvah naked and converted to Judaism, has married a history professor under the chuppah in the University Hillel Foundation chapel, and has been granted a divorce after six months under the guise of irreconcilable differences. She is not yet twenty-five. (photograph)

To say she does not know where she is headed would be true. To say the maps she was shown for her life were misleading would also be true. She is not a carefree adventurer, not without baggage. She is carrying an uneven load of wounded confidence and inchoate ambition, searching for a place she doesn’t even know exists. Terra incognita.

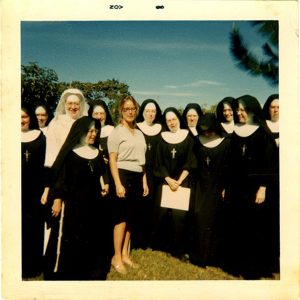

In a Polaroid photograph taken on November 4, 1965, the day I celebrated my twenty-fifth birthday in Costa Rica, I am surrounded by a bevy of twelve black-habited American nuns. I am the only one with visible legs. That afternoon, the nuns cluck around me as if I am a new hatchling. How I wanted that innocence, the easy erasure of my recent past, a fresh start. Were they recruiting me? I doubt it. Given my history, I was not a likely candidate. (Include photograph)

Thirteen years later, from 1978 to 1988, Ruth and I began an impassioned correspondence. After all this time, I still cannot fathom the spark that flew between us, the flame that kindled in each heart. These were times of deep transition, the critical years of my mid-life and Ruth’s early elderhood, one looking forward, the other looking back.

She was doing the work of social justice and living a politically radicalized life in Latin America, and I was still searching, a secular woman, a budding feminist, artist, writer and psychotherapist. Both of us craved a loving witness, someone with whom we could share thoughts, doubts, enthusiasms, reflections and ever-deepening intimacies.

Much of our need arose from a kind of emotional and intellectual loneliness, particularly in relation to family, but the subtext was always the question of our spiritual lives. We were kin, but also kindred spirits, two unlikely confidants who shared a mutual longing to be understood. Intimate collaborators, we discovered ourselves and each other by way of the written word: “I have so much I need to share with you . . . I wait with longing for your letter . . . . Can you just breathe this with me?”

In 1984, before visiting her in San Cristobal de las Casas in Mexico, I wrote to Ruth saying I felt inspired to write a book about her life. I had only ever written school papers and letters—a lot of letters to Ruth. In wanting to write about her, I was expressing my feminist interest in lifting ordinary women out of the ditch of obscurity.

No one asked me for such a favor, but I was convinced that Ruth’s life was a perfect subject. She never directly agreed or disagreed to the book idea, but during my visit she unloaded stories which I immediately scribbled into my journal each night.

No one asked me for such a favor, but I was convinced that Ruth’s life was a perfect subject. She never directly agreed or disagreed to the book idea, but during my visit she unloaded stories which I immediately scribbled into my journal each night.

Ruth died in 2003 at the age of eighty-eight. A shoebox held her earthly possessions, mostly photographs. After she died and I finally began writing about Ruth, I had almost two hundred pages of her letters. Written in cheap ball-point on thin blue airmail paper and onionskin, they were sent from Wisconsin, Germany, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua, carried by courier if local mail service proved unpredictable.

She never typed. I eventually did. The letters arrived at my various California addresses—Venice Beach, Palo Alto and Oakland—and later Maine.

With the exception of the few I copied, my letters were not saved. What I did have were two boxes of journals, an archive spanning my mid-life years from 1978 to 1990. They were the raw footage and in them I found the woman who wrote to Ruth.

The bridge my aunt and I built with words on paper carried us across the abyss of my midlife and her early elderhood. How flimsy these words on paper—how strong the handhold they provided.

I never did write the book I envisioned in 1984. Like one of those desert flowers that blooms every half century, the book finally blossomed into my memoir, Motherlines: Love, Longing, and Liberation. (SheWritesPress, 2016)

—

Author Bio: Patricia Reis’s memoir Motherlines (October, 2016) is her fifth book. Along with numerous essays and reviews, she has published four books of non-fiction: Women’s Voices, which includes her in-depth interview with naturalist and writer, Terry Tempest Williams; The Dreaming Way: Dreamwork and Art for Remembering and Recovery; Daughters of Saturn: From Father’s Daughter to Creative Woman; and Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing.

She produced Arctic Refuge Sutra (DVD) and appeared in Signs Out of Time, a documentary about Neolithic archaeologist, Marija Gimbutas produced by Starhawk and Canadian filmmaker, Donna Read. She divides her time between Portland, Maine and Kingsport, Nova Scotia. http://patriciareis.net/

Category: On Writing