My Breasts Don’t Smile…? Writing—and Writing as—Opposite Genders

My Breasts Don’t Smile…? Writing—and Writing as—Opposite Genders

Author Kristen Tsetsi. (Jessica Hill/Journal Inquirer)

In the 1997 movie As Good as It Gets, Jack Nicholson’s famous-author character is asked by a giddy, nearly trembling female fan, “How do you write women so well?” Turning toward her and advancing slowly into her personal space, he responds, “I think of a man, and I take away reason and accountability.”

There’s something wrong with that sentiment beyond what it says about Nicholson’s character’s view of women and the weak-kneed fan who identifies with his apparently irrational and irresponsible creations; it’s that going through the tedious effort of consciously and carefully removing basic human qualities needlessly increases his workload.

He’s thinking too hard.

As is any man who has to sit and ponder, “What would a woman do if, say, a fan were blowing across her body one hot morning after she survived a bear attack? Look at her boobs, maybe? Her nipples hardening in the…the breeze, or whatever?”

The distance between #notallmalewriters and their female characters isn’t always so obvious. Years ago, a fellow grad student and I were discussing a story that was to be included in that year’s literary journal, which we were team-editing.

In it, a male narrator is assessing a woman his age (50s, or so) before sleeping with her for the first time. He makes an observation about her breasts that my editing partner and I wanted the writer to revise if his intention wasn’t to be insulting. Our male instructor thought the description was fine as it was. So did the writer, until we explained the impact of the specific words he used.

The inability to empathize with the opposite gender can make writing about them, or writing from their point of view, challenging for some. One male writer may not recognize a negative/sexist connotation in the description of a woman’s breasts; another might be so clueless about what a woman could possibly think about or be interested in that he’ll devote an entire scene in his novel to her mulling over dresses in a little boutique (for no reason).

Enough men are challenged by this conundrum to have inspired The Mukhtaar Chronicles author Nat Russo to write a 12000-word instructional blog post on how men should approach writing female characters:

“Actively seek input from women around you. … truly listen to their stories, thoughts, and concerns. … Remember that women have diverse voices and perspectives…”

Russo is performing a valuable service, but that there’s a demand for it is disappointing, as is the notion that anyone anywhere needs to be told that women have diverse voices and perspectives. Reading his post, you’d think women exist in an utterly foreign culture that’s also so geographically distant from men that there’s no possible way for men to have organically absorbed any of this information.

In fact, most male writers have been exposed to girls and women in one way or another for much of their lives. For men (writers, no less, who we assume have some gift of insight along with a little imagination) to have no idea what a woman might feel or have opinions about would have to mean they’d either been hellbent on ignoring them or consistently, and cliché-ly, dismissing them as “mysterious” or “confusing.” (Dames, I tell ya!)

When I wrote the Dan Palace character in my novel The Year of Dan Palace, the only place I got stuck on his maleness was when it came to what his first thought would be upon waking up in his RV with Jenny, a young woman who’d finally managed to get him into bed, dragging a fingertip across his back. I had to call my dad. Hey, uh, say you’re a guy waking up next to… My dad gave an immediate answer so obvious and perfect it was clear I’d been overthinking it by wondering “What would a man think…?” instead of imagining a human being.

None of this is to say that I’m an exceptional writer for being able to get inside the head of my male character; it’s only to say that outside of some of the more obvious differences men and women experience in their lives (men: more power; women: less power; men: less fear; women: more fear), there’s no reason opposite-gender writing should be more challenging than creating any other made-up character.

We all know dread, relief, nervousness, sadness, jealousy, rage… On a hot morning after a bear attack, men and women alike would just be grateful for a fan’s cool breeze on a deep cut. No one would be looking at their nipples—or their morning wood.

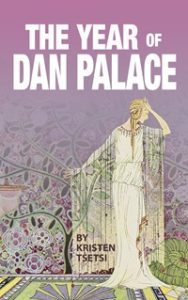

Still, the sex division persists, even among readers. That’s why when I first published The Year of Dan Palace it was under the gender-ambiguous pen name Chris Jane printed on a brown cover featuring lots of cogs. Masculine! My previous novel, about wartime, had been minimized for having been a woman’s story written by a woman, and I wanted readers to be introduced to Dan and his perspective without the filter/distraction of his having been written by a female. (What’s a girl know about a man’s midlife crisis, anyway?)

Still, the sex division persists, even among readers. That’s why when I first published The Year of Dan Palace it was under the gender-ambiguous pen name Chris Jane printed on a brown cover featuring lots of cogs. Masculine! My previous novel, about wartime, had been minimized for having been a woman’s story written by a woman, and I wanted readers to be introduced to Dan and his perspective without the filter/distraction of his having been written by a female. (What’s a girl know about a man’s midlife crisis, anyway?)

But I came to understand recently that the more we openly write about—or as—each other, the sooner we’ll recognize that we’re all basically the same, so I re-published the novel with my girly little name on a brand new, beautiful cover with a woman standing smack center-right.

Find out more about Kristin on her website https://kristenjtsetsi.com/

—

THE YEAR OF DAN PALACE

Nina is Dan’s wife.

Nina is Dan’s wife.

April is Dan’s ex-wife.

Jenny is a hotel worker in search of a future, and she thinks Dan can give it to her.

Dan is in his forties and wants something more. His quest to find that “more” will take him away from his wife and toward his ex-wife with Jenny hovering at his side.

The Year of Dan Palace is the story of one man’s mid-life crisis viewed through the lens of the female gaze. It’s also the story of a life – and what any of us might be willing to risk to live it to the fullest.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing