No Place is a Saint by Alison Stine

Pic by Ellee Achten

I live in rural, remote Appalachia. You may know this place from a bestselling memoir, or many national news articles on poverty, coal, disability, drugs, or politics—articles written overwhelmingly by people who never lived here.

Then you don’t really know this place at all.

Central Appalachia is the setting for my novel, Road Out of Winter, as it has been the setting for most of what I’ve written for the past decade or more. Some places imprint on you, and my home is one. But a trap I need to stop myself from falling into is describing it too beautifully.

We have cliffs, jagged foothills, caves, and wild dark woods. We also have a high rate of poverty and food insecurity. And yes, like all communities in the United States: drugs. We have neighbors helping neighbors and strangers—but we also have corruption, nepotism, and negligence on every level from the schools to the city government.

I love it here but I see and experience its problems too, and to write about this or any place, I need readers to see both. No person is a saint and no place is either.

So, there are farms in my novel, a family of outsiders who band together and fight for each other. There is also an overcrowded rural hospital. An injection well for fracking waste where the guard has left his post. A state park and a chemical plant.

My fiction is speculative. It’s not quite in this world. The storm in Road Out of Winter, for example, is unparalleled, beyond what we are experiencing even now in the grip of climate change. Snow falls, and it doesn’t stop falling. Spring is late, and it never comes back.

But beyond the unreality of the story—our world but slightly bent, tweaked sharper and harder—I want my work, even my fiction, to read as real.

The poverty is real in my book, as it has been real in my life. At a pharmacy, a character worries about how he’s going to pay for medicine. Other characters resist going to a hospital for injuries for just this reason.

These aren’t abstract ideas about poverty, but actual experiences I and my friends have had. I don’t write about real life—but I write from real life. And from a real place, which is an hour and a half drive from an airport. Over fifty households, in the next town over, don’t have running water.

You can list—and I have, in reported pieces researched and written for my day job in journalism—all the statistics in the world.

But nothing compares to the clear picture that comes from living. To take a nuanced view, you have to present the good and the bad, and the in-between, which is the most complicated aspect of writing.

Many folks in my area keep old junk cars. You might think that’s an eyesore, but the cars are used for parts, to keep other cars running, and for storage. Some families have relatives or friends living with them, and there isn’t enough space in homes or trailers for everyone’s belongings.

The creeks in my county run a deep, orange-red. It’s startling and unique. It’s also poison. To present these complexities, you have to know them first. To know them in your bones.

I think it’s possible to write a complex portrait of a place. But it requires a lot of visiting, if you don’t live there, and a lot of research. Not just the google kind. It involves talking to people who do live there—and not just your friends, or people like you.

My experiences as a single mother in Appalachia living below the poverty line are very different from that of a professor. At the same time, I’m white, and pass as abled and straight. I don’t experience life, including place, the same way as a single mother of color, one who has a visible disability (I’m hard of hearing, a disability many people ignore or don’t notice), or someone without family support.

I can spring for the expensive grocery store sometimes, rather than always relying on the discount one, which has a paltry selection of fresh fruits and vegetables—or the gas station mini marts, which have no fruits or vegetables, yet many people in my area depend on them for food.

My car is approaching twenty years-old, but I have family close enough to lend me a vehicle if mine breaks down or I need to travel. These experiences are part of my life here, but it’s not the same for everyone in this place.

One of the greatest and earliest skills a writer must develop is not plot or dialogue, but empathy. How can you write about someone else, even someone invented, unless you love them? How can you write about a place unless you feel it in your blood?

I live in the world, and I write from and about that world, even when what I write is miles or years away. You carry the world with you. Give it the respect and the clear, informed writing it deserves.

—

Alison Stine is the award-winning author of several books of poetry and short fiction. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, and many others. Road Out of Winter is her debut novel for adults. She lives in the foothills of rural Appalachia with her son.

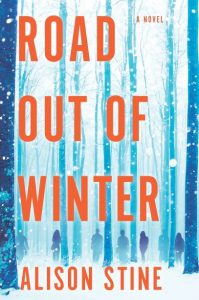

ROAD OUT OF WINTER

Road Out of Winter is a novel about a young woman who’s grown up working on her family’s marijuana farm. In an extreme winter, she leaves home, only to become the target of the leader of a violent cult. Because she has the most valuable skill in the climate chaos: she can make things grow.

Road Out of Winter is a novel about a young woman who’s grown up working on her family’s marijuana farm. In an extreme winter, she leaves home, only to become the target of the leader of a violent cult. Because she has the most valuable skill in the climate chaos: she can make things grow.

BUY LINKS:

https://www.harlequintradepublishing.com/shop/books/9780778309925_the-growers-tale.html

https://www.amazon.com/dp/0778309924?tag=hqnweb-20

https://www.indiebound.org/book/9780778309925

SOCIAL MEDIA:

https://twitter.com/AlisonStine

https://www.instagram.com/alistinewrites/

* * * * * * * * * *

ROAD OUT OF WINTER, pre-order: bit.ly/2QIosYn

http://www.alisonstine.com

Category: On Writing