“On Writing About the Unanswerable” by Joan F. Smith

“On Writing About the Unanswerable” by Joan F. Smith

When I was very small, one of my parents told me breaking a bone was the worst pain I could ever feel. Soon after, I was five years old with a broken wrist from the slide at our local McDonald’s, thinking, Well, I did it. If this is going to be the worst pain, then at least it’s over. (It wasn’t.)

When I was very small, one of my parents told me breaking a bone was the worst pain I could ever feel. Soon after, I was five years old with a broken wrist from the slide at our local McDonald’s, thinking, Well, I did it. If this is going to be the worst pain, then at least it’s over. (It wasn’t.)

Soon, I learned that people tolerate pain in different ways, that sometimes redheads need more anesthesia, that peanut butter could nourish one person and kill another. I learned tonsillectomy recovery can be nearly painless to one person but land me in the hospital. And those small differences, the things that we like and dislike, the things that ground us in who we are: They only made me want to know more. About life, people, humanity. Amid all these differences, I embarked on a quest for the thing that unites everyone on earth.

As a child, I first debated this information in locked diaries with colorful plastic covers, then in an ancient (vintage?) word processor my mother brought home from a yard sale before we could afford a computer. We lived in an eyesore part of an affluent town, in a condo complex that, like everything, had once been new. (I considered, then rejected, the unifier as being the simple process of breathing, because doing so in some form seemed like an essential part of living.)

I grew up and studied my friends, my boyfriends, characters on sitcoms, villains in movies. Surprisingly, it took me almost three decades to learn that when people refer to the voice inside their heads, they mean it literally. Many, if not most people have an inner monologue, where their thoughts are present in their heads like a movie narrator, as opposed to people like me, whose thoughts are abstract, nonverbal. It was yet another difference, one that only heightened my curiosity about why the brain works the way it does.

It led me to quiz my kids and husband about how emotions feel to them. For instance, when I ask them to describe what joy feels like in their bodies, my husband says his chest swells, my eight-year-old says her stomach feels butterflies, and my five-year-old says his legs want to jump.

Characterizing people, my writing teachers told me, meant making them human. And being human meant that no one was either wholly good or wholly bad. Complex characters, they intoned. My mother liked to power walk; my father liked to run. He’d complain about his joints after, about aging, even in his thirties. “Better than the alternative,” he’d say cheerily. At some point, I realized this translated to the concept that getting older was better than dying, and then, I thought: Oh. That was it. Death was the one thing we all had coming.

Before I was ten, I started clocking what people said about death. Soon, I figured out that the actual equalizer was that everyone has beliefs about death, but they vary. Before we stopped going to church, I listened to various priests and their stories of heaven. I gave the same attention to my chain-smoking neighbors, who told my parents they knew cigarettes would lead them to “the infinite dark” before their time. “Like a shade pulled over your eyes,” remarked the male neighbor, his words already wheezy.

It was the one thing I kept coming back to, the one thing that leveled everyone on earth. Death.

(This, the irony, that my father’s “better than the alternative” was such a refrain, when the alternative was what he chose when he took his own life. A complex character.)

Early on, another writing teacher called writing “the response to the human condition,” and so I studied psychology and continued to write and make jokes with my now-husband about the human condition. I doubled down on exploring the things that unify us—things that someone with dad-like humor would call “death and taxes.” In my early twenties, we went out to dinner, and because we were pre-children, we could order both appetizers and too much wine.

We discussed the things that make me want to know more—the topics that make my eyes light up and leanforward. These were the “what would you do” or “would you rather” questions, like Would you rather love or be loved? On a recent episode of Armchair Expert, Dax Shepard posits one of his dinner table questions: Would you go down 10 IQ points to be thirty percent happier? (Now, when these are packaged and sold like a deck of cards, I am the target consumer.)

Along the way, I have learned that the potential answers to those big questions—What happens when we die? Do we have free will, or are things predetermined, or is there a mix of both? Where did we come from? Why are we here? What is the difference between good and evil?—are what propel my stories. Survival stories, the hero’s journey, romance: they’re all about humanity, they’re all about life, and life is fairly inarguably the opposite of death. How we approach the answers to these questions is what drives our entire society. They shape everything from religion and politics to climate change rationale, they drive the wellness industry. They’re as fundamental as childhood in helping us develop our own sense of morality.

I took religion classes in college to get a sense of how each one treats death, the afterlife, reincarnation. Raising my kids has made me even more aware of death, too: They never got a chance to meet my dad, and they understand the concept of death. Unprepared, I have loosely described the place we go as “heaven,” but with no real concrete answers otherwise. I can’t figure out if this is frustrating, reassuring, or terrifying for them, and I suspect it’s a mix of all three. I dread the day I have to tell my kids the truth about how their grandfather died. So I write about it.

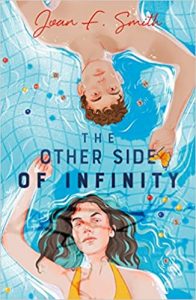

Two years before my father took his life, one of my very good friends was killed in a single-car accident. He was someone I grew up with since before kindergarten, my first good kiss. His death was how I learned grief. Someone I pictured in my life when we became adults was gone forever. (His death inspired my second book, The Other Side of Infinity[JS1] .) Everything we construct about death has a twofold purpose. One is to guide us in how we live our own lives, and the other is what makes us take comfort in our losses. My friend’s parents began going to a medium, and they were incredibly comforted by the details that medium offered. I was fascinated, equal parts believer and not; I filed this directly into the information bank.

Now, I get lost in TikToks about souls, I devour near death experience literature, and I regularly read medical journals on what happens to the body and brain at the moment of death. The overlapping opinions are surprising; the deviations even more so.

When I write, I do so with the confidence that the world would be a much different place if we did have these answers. When I consider this—what if we did know, what if something very unanswerable became answerable—I “what if” my way into my plots materializing. These are the times when I come closest to flow state (Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, 1975)—the “zone” of being completely and wholly immersed or absorbed in an activity. This hyperfocus is what I adore—the “thing” that feeds my passion.

I write to make this intangible become tangible. I write because I want the answers, but also, because no one could have them with any degree of certainty. Writers are always looking for hooks, and for me, this is the key to finding mine: exploring the things that many hold strong beliefs about, but no one knows with absolute, irrefutable certitude. Using a combination of logic, reason, and faith (or lack thereof), we can believe anything we want about anything we want. In many ways, uncertainty was what we could be certain about. Another thing that levels the playing field for all of us.

It’s better than the alternative.

—

Joan F. Smith is an author, dance instructor, and former associate dean of creative writing. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College. Joan lives and writes in Massachusetts, where she was the 2021 Writer-in-Residence at the Milton Public Library. When she’s not writing, she’s either wrangling her kids, embarking on a new hobby she will quickly abandon, or listening to podcasts on a run.

—

THE OTHER SIDE OF INFINITY

They Both Die at the End meets The Butterfly Effect in this YA novel by Joan F. Smith, where a teen uses her gift of foreknowledge to help a lifeguard save a drowning man―only to discover that her actions have suddenly put his life at risk.

They Both Die at the End meets The Butterfly Effect in this YA novel by Joan F. Smith, where a teen uses her gift of foreknowledge to help a lifeguard save a drowning man―only to discover that her actions have suddenly put his life at risk.

It was supposed to be an ordinary day at the pool, but when lifeguard Nick hesitates during a save,

seventeen-year-old December uses her gift of foreknowledge to rescue the drowning man instead. The action comes at a cost. Not only will Nick and December fall in love, but also, she envisions that his own life is now at risk. The other problem? They’re basically strangers.

December embarks on a mission to save Nick’s life, and to experience what it feels like to fall in love―something she’d formerly known she’d never do. Nick, battling the shame of screwing up the rescue when he’s heralded as a community hero, resolves to make up for his inaction by doing December a major solid and searching for her mother, who went missing nine years ago.

As they grow closer, December’s gift starts playing tricks, and Nick’s family gets closer to an ugly truth about him. They both must learn what it really means to be a hero before time runs out.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing