On Writing INVINCIBLE WOMEN and an excerpt of ISABEL ALLENDE interview

A multitude of conflicting forces drove me to write Invincible Women. Every interview was encouraged by our glorious women’s movement, the universal bonds of sisterhood, and the growing voices of #MeToo. Equally strong was my need to tell powerful stories to refute the policies that stuff certain immigrants into one faceless group. No matter where they come from, how hard they work, or how American they are, we constantly hear that “they” do not belong here. The indiscriminate targeting of immigrants from certain countries and the uncertainty and lack of protection facing the Dreamers resonated with me. The escalation has continued with the removal of children from their families crossing the US southern border.

A multitude of conflicting forces drove me to write Invincible Women. Every interview was encouraged by our glorious women’s movement, the universal bonds of sisterhood, and the growing voices of #MeToo. Equally strong was my need to tell powerful stories to refute the policies that stuff certain immigrants into one faceless group. No matter where they come from, how hard they work, or how American they are, we constantly hear that “they” do not belong here. The indiscriminate targeting of immigrants from certain countries and the uncertainty and lack of protection facing the Dreamers resonated with me. The escalation has continued with the removal of children from their families crossing the US southern border.

While I continue to grapple with the unfairness of the present situation, I understand we must make the United States a safe country. That means being vigilant and aggressive about who is allowed to enter. And that requires responsible and thoughtful policies, education, and practices. Listening to these stories, as I watched the tears fall and waited for the deep cleansing breaths to pass, I imagined the added fear that immigrants now face.

This reality prompted me to begin the journey of my book. As I met and spoke to these women and dug out their inspiring life stories of struggle and survival, I identified with them because parts of my life mirrored theirs. My resolve to write and celebrate their contributions to the world was strengthened daily.

The women I interviewed are all American immigrants who arrived here at different ages. They came as long ago as 1936 and as recently as the 1980s. They escaped the atrocities of war, or fled wounds of a more emotional nature. Their reasons for leaving the countries of their birth are as varied as their skin tones. They came from Iran, Pakistan, Haiti, Armenia, Israel, India, Austria, Argentina, Brazil, Rwanda, South Korea, China, Chile, Serbia, Transylvania, Egypt, and Bangladesh. They are now all United States citizens.

These women have achieved greatness; some are famous and some not so much. You will see how each made her neighborhood, her region, and our planet a better place to live. Their stories, told in their own words, describe incidents of racial and religious discrimination. They quit unwanted relationships, avoided capture, and sacrificed dearly. They learned new languages and new customs, and figured out how to live as “the other” yet still retain a strong sense of self.

Back home they tasted the fear of dying as Nazi troops swept through Eastern Europe and death squads invaded Rwandan villages. They felt suffocated by patriarchal societies and rampant gender discrimination. And once here, they were often crushed by loneliness and separation from friends and family. Though some of the paths are so horrific you may want to look away, I ask that you keep your eyes open. By reading about their journeys, we can learn about their tenacity and what makes a positive influence and future role model for our children.

The process of writing has enriched me and the subjects of this book, with whom I developed friendships after coming to know intimate details of their lives. Some of the women told me that the very exercise of revisiting their stories crystallized a full life’s circle. Most of us, they said, never really take the time to reflect because we just go through life in the moment.

One day I invited five of the women to my home to get acquainted. But they insisted that I tell my story first! Immediately I understood how they felt when I interviewed them. I got a clear picture of my life, of where I started, and where I am now.

One day I invited five of the women to my home to get acquainted. But they insisted that I tell my story first! Immediately I understood how they felt when I interviewed them. I got a clear picture of my life, of where I started, and where I am now.

As an immigrant, I had a vision, a purpose, and a mission to become a doctor, like my father. I’m Israeli, and I went to medical school in Italy. When I came to the United States, I came to stay. Soon after, I enrolled in a residency program that made me feel secure in the sense that I knew my future was determined. Similar to other immigrants, I struggled to learn the language. At the time, I was the only woman in my residency working with physicians from a range of nationalities and cultures.

Following my pediatrics internship, I decided to enroll in a radiology residency and fellowship. I enjoyed the intellectual aspects of this field and the more accommodating hours. This permitted me to expand my life beyond medicine to hopefully become a devoted mother and wife, and to be able to care for my aging parents.

In America, I felt integrated but different. Here I was welcomed and empowered to maintain my own “self ” among so many other cultures and beliefs. Here one could become a citizen and still feel proud of one’s mixed heritage. I also saw that this country is unique in providing opportunities to give back. I can’t imagine being able to do in any other country what I did on Long Island: Manhasset Diagnostics Imaging, a multidisciplinary radiology practice; Pathways Women’s Health Center, which provided pro bono educational seminars for women; the Unbeaten Path, a seminar series for teens; or Nassau Physicians Foundation, providing financial support for medical research.

Our fears are exacerbated by a constant thrum of tweets, videos, and text alerts. Headlines bombard us with demands for ICE raids and border walls, pushing us back under the covers of our warm beds at night, safe from people we do not know.

I hope you develop admiration and empathy for the women in this book as you step into their shoes. And I hope you begin to see how grateful we immigrants are to America for the opportunities we have received—and for the chance to share our own talents and passions.

—

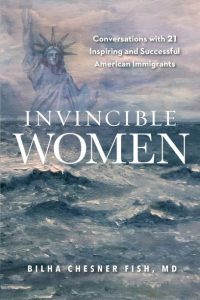

Excerpted from Invincible Women: Conversations with 21 Inspiring and Successful American Immigrants by Bilha Fish, publishing May 14, 2020 by Hybrid Global Publishing.

ISABEL ALLENDE INTERVIEW

After a military coup in Chile, you found safety in Venezuela in 1973. In 1987 you decided to immigrate to the United States. How did these different situations affect you?

In the first circumstance, I was a political refugee. I left my country because I couldn’t stay, and I chose Venezuela because there were not very many choices. Very few countries accepted refugees from Chile. There were no visas given for Chileans in places like Costa Rica, Mexico, and others. Venezuela was a democracy. I could speak Spanish, and being a journalist, language was important for me. It was open for immigrants and refugees and whoever wanted to come to work.

It was very difficult for me because I didn’t want to leave my country, and I was always looking back. The experiences at the beginning were like paralysis and nostalgia, and very different from the experience of an immigrant. The immigrant chooses to go, and usually it’s a young person who’s looking at the future, not looking at the past, not thinking of returning, but thinking of establishing in another place. After all, we had kids and grandkids. So the emotional state of an immigrant is very different than a refugee. I would say that the experience of being an immigrant is much, much easier than being a refugee.

So in 1989, you immigrated to the United States, following your American husband William Gordon, and became a citizen in 1993. Did you feel comfortable right away?

Well, I came to the United States although I didn’t like the country at the time. The CIA had been involved in the military coup in Chile, so I had the feeling that America was one of my enemies really. It so happened that when I was on a book tour, I met a man, I fell in love, and I moved to be with him. That facilitated everything, not only my legal status in the US. I came with a tourist visa, but then we married, so very soon I applied for residency and a work permit.

My husband opened all the doors for me. The problem when you are new in a country, like in Venezuela, for example, and actually everywhere, is that you don’t know the rules of that country.

Sometimes you don’t even speak the language, and you don’t know how to get along and how to do things. For example, after living in Chile and Venezuela, I didn’t know that you could pay a bill with a check in the mail. I couldn’t believe that. It was just extraordinary, and there were many other things, both good and bad. My husband chaperoned me during the first few years until I learned the language and could have a life of my own.

—

Category: On Writing