On Writing Lost in Ibiza

On Writing Lost in Ibiza

I have always had a complex relationship with writing. Philip Roth put it very succinctly. “Writing isn’t hard work, it’s a nightmare.”

I have always had a complex relationship with writing. Philip Roth put it very succinctly. “Writing isn’t hard work, it’s a nightmare.”

Lost in Ibiza is my 3rd novel and it took me many years to complete. My husband, a television producer, strongly advised me not to discuss the inordinate length of its gestation in public. He was worried I might sound a little intellectually challenged. But I’m going to recklessly disregard him and offer full disclosure. From first outline to publication, it has been 14 years. I want to say in my professional defence that during that time I also researched, wrote and produced Misbehaviour, a feature film about the women’s movement that was released in 2019, and set up Can Pep, a regenerative honey farm on top of a mountain in Ibiza. But still, which ever way you slice it, 14 years is a very long time to do battle.

I wanted to foreground a story about the fascinating collision of modern day tribes who have colonised Ibiza, an island I had lived on for some while. But I was determined to try and wrap their story around an environmental theme – I had done a lot of environmental activism over the years and everything else seemed dwarfed by the scale of the issue. I knew that no one would want to read a book that was explicitly about environmental issues. At least I knew I certainly wouldn’t. So I knew my challenge was to create characters and a story that might compel the reader with sufficient momentum that both story and characters became in effect a Trojan horse for the larger issues. And the premise that emerged was a father and daughter meeting for the first time in Ibiza. The father William, is a wealthy property developer, while his daughter Alice, is a 21 year old environmental activist.

I often think that the process of writing a novel is like setting out to sea, knowing you won’t glimpse land for years. Despair and rage are my constant companions throughout this interminable period and there are always particularly challenging low points where I literally lay my head on my desk, overcome by a bone weariness at how horribly out of my depth I feel. The thing that keeps me going is that in each new draft, new glimmers of something promising do often emerge. And I am so relieved at their miraculous appearance, I feel compelled to try and rescue them. And the only way to rescue them is to keep revising all the dross that is holding them back.

Once again, Philip Roth is so on the money. “You’re always lost at the beginning. You’re maybe so lost that you don’t even know what you’re going to write about. Then when you discover what you’re going to write about, you have no idea how you’re going to go about doing it, and the sentences are ugly and clumsy and awkward and you can’t imagine that you could ever reach competence again. And then gradually over time, as you come to grips with the subject, the manner begins to be more apparent and easier to handle.”

I hammered away. Draft after draft. At some stage in those early lost years, I realised with a sinking heart that I was going to have to fire one of the main protagonists. He was a dissolute musician, reminiscent of Pete Docherty, and I had done a lot of work attempting to bring him to life. In search of authenticity, I had read all Pete Docherty’s published diaries and various biographies about his stormy exploits. My character was called Magnus. But try as I might to integrate Magnus, it was increasingly apparent to me that he was in fact only impeding the stories progress. Once I finally gathered the courage to hit the delete button, Magnus vanished in a cloud of cigarette smoke, issuing foul mouthed expletives over one shoulder. But released from his maverick energy, the novel slowly began to settle into its moorings.

It’s the final leg, when the wind starts to come into your sails, that is the compensation for all the long struggle that has preceded it. It can feel as if the high is a precisely proportional inversion of the depth of misery the majority of the process has entailed.

The final story is told by 4 characters with wildly divergent world views, whose lives collide and collapse over 4 days. The imagination is a very curious thing. A mystery often most particularly to the person trying to do the imagining. Once Magnus had been dispatched in a cloud of expletives, to my great surprise, Mary stepped in to fill the gap with the shrewd eye of an outsider, veiled by the decorous manner of a domestic servant. If Magnus was moral chaos incarnate, she became the moral centre of the book. She is a Filipino house keeper, an economic migrant who has had to leave her young daughter behind in the Philippines. She is the perfect foil to the white privilege she is employed to service. The salt in the bread. And it was really only as she began to reveal herself to me that I finally made out the distant glimmer of land on the far distant horizon and dared to hope my time at sea might at last be drawing to an end.

—

Rebecca Frayn is the author of Lost in Ibiza, published on 18 April by Whitefox.

Rebecca Frayn is the author of Lost in Ibiza, published on 18 April by Whitefox.

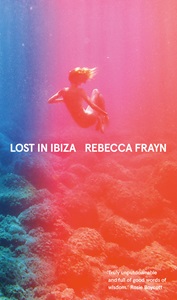

LOST IN IBIZA

On her twenty-first birthday, environmental activist Alice learns that the man who has raised her is not her father after all. She is surprised to learn that her biological father, William, is a property developer based in Ibiza, where he is immersed in a huge deal that will further increase his wealth.

Alice and William meet for the first time in Ibiza, inadvertently finding themselves on a road trip across the island, unravelling secrets from the past and glimpses of the future as they go.

Seen from the perspective of four characters with widely divergent world views, Lost in Ibiza offers an intimate meditation on family dynamics, set against the larger canvas of an island utopia that teeters on the brink of environmental catastrophe.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing