Persona: When the Voice Is Not Your Own

This whole process began with hearing voices.

This whole process began with hearing voices.

I was working in my journal one night when this voice began, with no prodding, no expectation. It was strong and sure, a woman’s voice, dictating lines, whole poems. The first scribbled line was, Well I guess this is the freak show. I was shaken, to tell the truth. The voice was Appalachian, at least in part—that accent I recognized, and took some comfort in. That was the sound of home. But then came this soaring rhetoric… be awed by my God-inflected body, lazarous, the brands of divinity— see the thumbprints on my anklebones, the wound His mouth pressed into my neck…. Was that even the same voice? Where was this coming from?

The Greeks spoke of “the muse” and of inspiration, a literal breathing in, and Christian mystics wrote about fiery words and arrows that transfixed their bodies. This wasn’t nearly so dramatic, but it was equally Other. I scribbled as fast as I could for as long as she spoke, that night, thirteen pages that included three poems almost whole, chunks of others, and fragments as cryptic as a psychic’s warnings. But fascinating as this visitation was, I also had a strong impulse to turn it off, turn it away. The story began to take shape, of a biracial woman from an era before mine and the carnival she called home. It was a world all but unknown to me. And so, dismayed, I focused on other projects, for more than 15 years, writing two novels and another book of poetry. But the poems kept coming.

One of the three poems that arrived complete on that first night was “The Leopard Lady Speaks.” It would become the opening poem as it lays out some of the threads of this narrative.

The Leopard Lady Speaks

This leopard-skin come onto me

when I lost love,

(this is not for the marks to know)

when my man’s absence

set a hot kindle of distrust

that blowed back on me

as lack of faith

in what is more worthy

than some handful of spit and dust.

No wonder I lost

my natural color, trying to be

all things to him, and him not wanting

what I ever was or become or any between—

turning away like a spoiled child,

turning away like the sun eat up

by the moon, and not my doing

or undoing.

I scourged my soul,

turning myself inside out

to make him a better tent

against the weather of the world,

stretching myself across his failings

like a worn-through quilt

on a wide cold bed.

They weren’t enough left of me

to fill a thimble, then,

but I gathered myself back up

and stood, feet reasonable

to the earth, liver’n lights settling back

like I’d been dropped

from a high place,

and I was about satisfied,

but the letting-go of that man—

him of me then me of him—

left me streaked, specked, and spotted

like the flocks of Jacob,

and I opened my mouth to say

the true things that underprop the world.

Her voice is so distinctive, sharp-edged words from a gentle heart. She’s an observant person, with a good bit of worldly wisdom even when young. The old woman who takes her in teaches her the art of palmistry, and in response to a comment about her love lines, Dinah says: “Most like she’s tipped that The Patch has me warming his bed,/dues paid to be kootching and not set down side of the road. /But that aint love nor neither is it heartache.”

Bits of my own life history became part of Dinah’s, as is the case with most everyone’s writing. “I was born of a Wednesday and full of woe, so they say.” (As a Wednesday child, I always hated that rhyme, the only day of the week to have a completely negative description.) Dinah found a life that was, in fact, full of woe. I had to listen long and hard for her story, and often it was hard to write. Her “adoptive” family effectively turned her into a slave, and the father sexually abused her—little wonder that she took off at 14 with a man who passed by on the road. She ended up joining a carnival near Oil City, PA—not too far from my childhood home in western New York. Nearly every poem in this collection has some such point of personal reference, allowing me an anchor in this unfamiliar voice and alien place.

While I could tease out some of the sources of this voice, others remained unknown. Each time I stepped into one of Dinah’s poems, her awareness covered mine, and it almost seemed that I became the persona (which means mask in Latin), adding my insights or bits of research to a very real presence. One definition of persona is the role adopted by an actor, yet it seemed to me less that I was adopting an identity than being filled by one. I’ve written in persona, many times, but never was the Other so strong, nor did it persist for more than the length of a single poem.

Going back to that first night. I’ve learned from other writers and from reading a 2017 article in the New Yorker, “The Voices in our Heads,” that “hearing voices” is not uncommon for writers. A British researcher questioned writers at an Edinburgh conference and found that 70 percent said that they heard characters talking. He added that, “As for plot, some writers asserted that their characters ‘don’t agree with me, sometimes demand that I change things in the story arc of whatever I’m writing.’”

Most of the poems in the book demanded to be told. A few were written as the book was coalescing, to add needed historical context or flesh out a character’s life events. Some poems, particularly Dinah’s observations of wild creatures, seemed at first not to be part of the collection but proved to have a place. And the universe tends to drop things on you when you need them—a chance encounter with a book at a friend’s house in Beaufort, SC, brought me the story of the “conjure man” Dr. Buzzard, root working, and revenge. The story leaped to life.

Leopard Lady’s story is one of exploitation and abandonment and loss and wandering and faith, all against the background of a carnival sideshow in the mid-20th century even as that form of mass entertainment faded away. As I worked on the poems, a life trajectory emerged for Dinah, gifted with second sight and then afflicted with vitiligo, an autoimmune disorder that destroys the skin’s melanin in patches.

From The Leopard Lady at the Market

…Now I am half one thing half another

they say, but I am only one creature

in this world. My father’s skin set me

out as a Negro, so called, but only half

of me harks to my father,

and I do not carry his name,

so why am I any more beholding

to him than to my mother,

who grew me up in her own body?

They say she was Irish, a folk

gifted with second sight,

that much and her red hair come true,

but the rest of her is folded

inside me, blood and bone.

She’s working to get out, though,

showing herself.

That white woman what left me

is taking me back,

inch by inch….

She struggles to understand the parents she never knew, the heritage she was robbed of, and who she is in the world even as she is changing. Vitiligo created “spotted people” who were exhibited in the shows, going back to the 18th century, and it’s something that I share with Dinah. There, at least, our personal histories merge, as well as in Elizabethan words and phrases pulled from well-loved volumes of Shakespeare and the King James Bible that were the texts for her self-education.

So much of this book is set in small towns in the mountains and the South. I grew up in such towns, and the arrival of a carnival was a big event. We were cautioned by our elders, as Dinah was: “I was oft told, back on the farm, to stay/clear of gypsy folk and carneys or they/ will steal you off, but I was already stole.” I set “What I Could See,” in which Dinah recalls her love affair with Shelby, in Eden, NC—but in its earlier incarnation as three separate cotton mill towns, before they were fused and took the name from an early explorer’s comment that this was the “Land of Eden.” I worked there as a newspaper bureau chief when I first came to North Carolina.

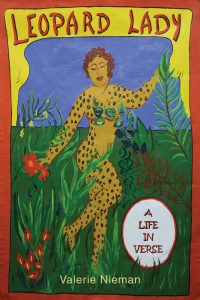

The poems that became Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse include those first thunderclap pages, but also would draw on legend and carnival lore and, as noted, pieces of my own history, shaping a narrative that is part voice, part personal, part research. Once I decided to accept the challenge of this project, I revisited books I had read over the years, such as Leslie Fiedler’s Freaks and Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, and I sought out websites and books on carnivals and freak shows so that I could accurately reflect this world. A friend provided books from his extensive personal library: Freakery by Thomson, The American Circus by Culhane, American Sideshow by Hartzmann, and Secrets of the Sideshows by Nickell. I enrolled in a painting workshop at the Coney Island Museum, another way of pursuing this story like the reporter I once was. I had originally planned to do the sideshow workshop, learning how to swallow swords and spit fire, but I chickened out. I’m glad I did, because I was able to work with Professor Marie Roberts to create the sideshow banner that helped me better see Dinah, and which became the book cover.

As compelling as Dinah’s voice is, it ended up having company. The lot manager arrives in a couple of places, as well as the outside talker, what civilians call a “barker.” In “The Ballyhoo,” he provides an alternative, more titillating life story for the Leopard Lady, who has many in the course of this book. That poem was written in the French verse form alexandrine. I’m not sure why, but the long lines seemed right. Dinah always spoke in free verse. When another voice appeared along the way, a world-weary voice, yet young, I was puzzled about its form. Eventually it settled into blank verse, like Milton and Shakespeare. The Professor or “inside talker” is not wise like Dinah through lived experience, but is book-learned. His dialogs with her shape the second half of the book into an exploration of faith and suffering, disillusionment and hope.

The Calling

I thought I heard the voice of God when I

was eight—a clear snap of something breaking,

a twig or bone, and in the space that was left,

my name. Jonathan. Oh, Jonathan.

Episcopalians, all, on my mother’s side,

a glory of gold and lace and proper tales

of vocation. Noah walked with God, I learned,

and laggard Moses heard his name twice called.

In Sunday school and seminary, I

sought out the stories. I labored in the fields

of Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek, as if

new letters would invite that voice again.

I did not ask for the earthquake nor the fire,

nor the great and mighty wind—only the still

small voice to once more say my name. Instead

it was ma lekha po, why are you here?

What had I to do with God? I walked

and waited, slept and sighed, dreamed for a dream,

but the lamp of God had long ago gone out,

and never again was my name called in the night.

Poet Kathryn Stripling Byer, the late poet laureate of North Carolina, gave me real encouragement as I was starting to engage with the book but remained cautious of the material. At a master class, she said the issue is, why do I need to tell THIS story? I don’t yet have an answer, but the words of Toni Morrison buoyed me: “The ability of writers to imagine what is not the self, to familiarize the strange and mystify the familiar, is the test of their power.” It is also something that Dinah addressed, “familiarizing the strange” for the gawkers gathered under the tent.

A side note to all this: I only knew the name Leopard Lady for quite a long time. But I knew she had to have a name. Hannah seemed right for a while, then didn’t. Dinah appeared. I went hunting its origins and found that it meant “judged” in Hebrew, and Dinah settled into her moniker for a long time before another random encounter brought me the information that “Dinah” was shorthand for any black woman during the Reconstruction and after. Union soldiers called enslaved women “Dinah” and in 1865 The New York Times called on the liberated slaves to demonstrate that they had the moral values to use their freedom effectively: “You are free Sambo, but you must work. Be virtuous too, oh Dinah!” So her naming by the Gastons has overtones of that racist history as well as Old Testament tradition.

The poems became a chapbook, became a book, but I go back to those early pages buried deep in a red folder of notes, research, scraps, and those pages from that first night, a scrawl in my wretched handwriting. What is the essential conflict in Leopard Lady—the search for an authentic self behind the masks, the prejudices.

And on another page, the question that sent me on the long search that ended in this book, Who is the Leopard Lady? She’s me, and she’s something entirely other that entered the world through me.

—

Valerie Nieman’s third collection, Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse, features work that has appeared in The Missouri Review, Chautauqua, Southern Poetry Review, and other journals. Her writing has appeared widely and been selected for numerous anthologies, including Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods (WVU) and Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology (U Georgia).

Valerie Nieman’s third collection, Leopard Lady: A Life in Verse, features work that has appeared in The Missouri Review, Chautauqua, Southern Poetry Review, and other journals. Her writing has appeared widely and been selected for numerous anthologies, including Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods (WVU) and Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology (U Georgia).

She has held North Carolina, West Virginia, and NEA creative writing fellowships. She teaches workshops at John C. Campbell Folk School, NC Writers Network conferences, and many other venues.

Her readings have included the WTAW series in Pittsburgh, Piccolo Spoleto, and Joaquin Miller series. Her fourth novel, To the Bones, is coming out from WVU Press in spring 2019. A graduate of West Virginia University and Queens University of Charlotte and a former journalist, she teaches creative writing at North Carolina A&T State University.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing