Publishing a Debut Novel at 65: Too Late, or Right on Time?

By Donna Gordon

Publishing a Debut Novel at 65: Too Late, or Right on Time?

At the age of 65, I’m not the first person to publish her debut novel later in life. Laura Ingalls Wilder was 65 in 1932 when she published her first book, Little House on the Prairie. Bram Stoker didn’t publish Dracula until he was 50, and Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, was published when he was 60. To date, the oldest living debut novelist on record was 93-year-old Lorna Page, whose novel, A Dangerous Weakness, was published in 2008.

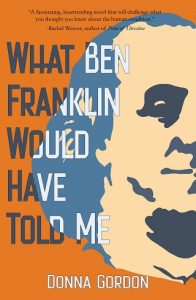

At first glance, the road to publishing a first novel would seem to require the stamina of the young. There are definitely more obstacles than there are open doors for a first-time novelist. Though there were long gaps in my writing career, and a series of what felt like perfunctory rejection letters, I never believed I wouldn’t find a way to bring my novel, What Ben Franklin Would Have Told Me (Regal House, June 8th, 2022) into the world. More than anything else, it had to do with the persistent music of language in my brain and a belief in my characters and their story.

I had some early success as a writer. I graduated from Brown and was then a Stegner Fellow at Stanford. After college I moved from Providence, RI, to Cambridge, MA, and worked part-time as an editor while living in a rooming house on Harvard Street, which I shared with clever mice and sewer roaches. My tiny studio apartment did not have its own bathroom. My head nearly grazed the low ceiling, and my stove was not connected to a chimney. The first time I tried to bake something in the oven, I burned a hole in the wall. But what mattered most was that I could afford it. I had a “room of my own.” I had been financially independent since college, working student jobs on campus and spending summers working in Cambridge.

Upon graduation, I accepted a job as an editor at Harvard Medical School. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, when I wasn’t working, I took the T from Cambridge into Boston, and the Boston Public Library in Copley Square became my office. I knew all of the street people who camped out in the library’s sprawling lobby arm chairs with their sacks and suitcases; I knew the staunch blonde woman with the leopard coat who set her hair in pink plastic rollers in the public bathroom; the long-haired man in fatigues who muttered aloud and sucked his thumb and stank of BO. I’ll never forget the day I was sitting at a table in the mezzanine, reading Margaret Atwood’s The Animals in That Country, when I became aware of a teenaged boy crawling along the floor, one hand in my backpack where my wallet was. When I shouted, he ran.

During those years in my early twenties, I started a novel, Cave Paintings, and became a PEN Discovery and a Ploughshares Discovery–the novel came very close to being published. Gordon Lish of Knopf called to say he loved it. I had a hot agent who had been the cover story on Poets & Writers. She sent my novel to 12 editors before calling it quits.

Enter marriage and the hard work of children, managing a family while my husband grew his business, the endless playdates, school lunches, art parties, religious school, puberty, learning issues. I was caught up in family dynamics, and was also guardian to my older sister, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. All the time, I kept searching in the back of my mind for the person who had gotten lost: Where was I? I had suppressed what I needed most—an open road to self-expression and the confidence to keep going.

The responsibility to myself disappeared almost entirely and became a responsibility to others. I can’t blame my generation; it was me who was “old-fashioned.” I had plenty of female friends who were waging careers. Somehow, I didn’t think I deserved one, or maybe I thought that the job of being a fiction writer–which for the most part didn’t pay anything—didn’t deserve respect. A published piece could pay in contributor copies, or it could pay $25 for a poem, $150 for a short story. But payments were few and far between. It took months after submitting, waiting for editors to make decisions. As my kids got older, I began working as a business editor. I freelanced for the Boston Globe Magazine writing features. But something was still deeply wrong. I felt almost physical pain having gone without writing fiction for so long. Inside, I still believed I was a writer. It became a kind of silent scream.

When I was 57, I reached out to another writer friend who had recently moved to town; she was about my age, and struggling, too. We formed a writing group with one other woman. Our monthly meetings gave me the structure I needed to take what had become the beginning of a new novel, and move the book along. I surprised myself with the way in which the story came alive. I learned to be accountable to myself in a new way by being accountable to my characters. I had created them, but they had also created me.

There’s no such thing as being too old to write. At 65, I’m as active and fit as anyone. I play tennis several times a week and swim regularly. I’ve already started working on another novel, and am finishing a collection of short stories. The hurdle of having published my first book is behind me. I’m no longer a writer, but an author. I’ve asked myself how I would have felt if I had come to the end of my life and hadn’t made this happen. I know I would have been filled with regret. I would have felt I’d let myself down in the deepest way. It’s never too late to write things down, or read them aloud. It’s never too late to stand up and be counted.

—

Donna Gordon, a fiction writer and visual artist from Cambridge, MA, is the author of WHAT BEN FRANKLIN WOULD HAVE TOLD ME (June 8, 2022; Regal House), for which she received the 2018 New Letters Publication Award, and was a finalist for the 2019 Black Lawrence Press Big Moose Award, and a semi-finalist for the 2019 Dzanc Books publication award, the 2019 Eludia Award, Hidden River Arts, and YesYes books awards.

Additionally, Donna was a 2016 finalist for the New Letters Alexander Cappon Prize in Fiction, and earned an honorable mention from Glimmer Train in 2017. She was a 2017 Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers Conference, and a fellow at the Vermont Studio Center in 2017 and 2018. Her work with former political prisoners culminated in “Putting Faces on the Unimaginable: Portraits and Interviews with Former Prisoners of Conscience,” exhibited at Harvard’s Fogg Museum. You can visit Donna online at donnasgordon.com.

WHAT BEN FRANKLIN WOULD HAVE TOLD ME

(June, 2022; Regal House Publishing ) explores the story of Lee, a vibrant thirteen-year-old boy who is facing premature death from Progeria; his caretaker Tomás, a survivor of Argentina’s Dirty War, who is searching for his missing wife, who was pregnant when they were both “disappeared;” and Lee’s single mother, Cass, overwhelmed by love for her son and the demands of her work as a Broadway makeup artist.

(June, 2022; Regal House Publishing ) explores the story of Lee, a vibrant thirteen-year-old boy who is facing premature death from Progeria; his caretaker Tomás, a survivor of Argentina’s Dirty War, who is searching for his missing wife, who was pregnant when they were both “disappeared;” and Lee’s single mother, Cass, overwhelmed by love for her son and the demands of her work as a Broadway makeup artist.

When a mixup prevents Cass from taking Lee on his “final wish” trip to Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia to pursue his interest in the life of Ben Franklin, Tomás–who has discovered potential leads to his family in both cities–offers to accompany Lee on the trip. As one flees memories of death and the other hurtles inevitably toward it, they each share unsettling truths and find themselves transformed in the process. Set during the Ronald Reagan presidency, this lyrical novel transcends an adventure story to become a beautiful journey which explores love, family and the inevitability of change.

Category: On Writing