Pursuing a Dream Across Two Continents

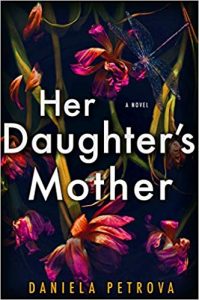

“Beyond the beautiful cover, Daniela Petrova’s debut novel is absolutely dreamy and suspenseful.”—O, The Oprah Magazine

Daniela Petrova

The urge to write—that burning desire to record thoughts, to make up stories and people —has always been with me, even though being an author was a forbidden dream I’d had to squash down for most of my life.

The urge to write—that burning desire to record thoughts, to make up stories and people —has always been with me, even though being an author was a forbidden dream I’d had to squash down for most of my life.

I grew up in a poor working-class family in Bulgaria during the Communist era. My mother and I shared a room in my grandparents’ one-bedroom apartment. While my uncle had the living room, my grandparents slept on a pull-out couch in the kitchen. I didn’t have many toys—I remember only two dolls—but I could check out as many books as I wanted from the library. I wrote my first poem in third grade. We had an assignment at school to recite a poem about the children partisans who had died fighting the capitalist government. I’d forgotten all about it until I went to bed the night before. I had no choice but to compose one myself before falling asleep. When the next day nobody figured out that I’d made it up, I was beside myself. I’d discovered a new game and I wasn’t going to stop.

As a teenager I began experimenting with short stories. Following the encouragement of a young history teacher who read one of them, I allowed myself to dream of becoming a writer. But pursuing it was a luxury I didn’t have. Because if I failed, I had no safety net. As the only one in my family to graduate from high school, I was expected to have a profession, to do something with my education so that I wouldn’t end up working on the conveyor line like my parents and grandparents.

Architecture seemed to be the only creative option. I enjoyed stretching my imagination, getting lost in a project, making something out of nothing—but I missed storytelling. I was more interested in people than buildings.

My dream of becoming a writer became that much more unattainable when in the spring of 1995, at the age of 22, I moved to America, barely speaking any English. I’d dropped out of the university for architecture in my third year to marry an American of Bulgarian origin I’d met in Sofia two years earlier.

My husband was the superintendent of a luxury building on the Upper East Side. Without any prior experience or references, I struggled finding a job as a cleaning lady. Meanwhile, I took ESL classes at the YMCA and checked out books from the library I’d already read in Bulgarian to help me with learning English. I could barely string words together in grammatically correct sentences but that didn’t stop me from writing poems. The audacity of youth.

Eventually, I made my way to Columbia University. By then I’d gained enough awareness to know that my English was too limited to pursue writing. Only in my final year did I allow myself to take two creative writing classes as electives. Hearing the other students read their beautifully crafted pieces only reconfirmed how ludicrous it was for me to even imagine a future in writing. But I loved it, and these classes were meant to be fun, so I swallowed my pride and focused on learning and enjoying myself. I had just gotten divorced and this was my opportunity to refocus on what was important to me.

One of my teachers invited me to join her private writing class. It was a group of only women, a safe space for me to make mistakes, to admit to a dream that was so out of reach. I got back my pages covered in edits. If there was one sentence that worked as it was, I considered it an achievement. The help and encouragement I received from my teacher and the women in the group over the years was invaluable, especially when the people closest to me didn’t support me. One boyfriend told me I was delusional to think I would ever publish a novel. Another one, a writer, excused his lack of support by claiming that he wanted to spare me the pain of failing.

As the years passed and I abandoned one career for another, never satisfied, I kept writing. I took classes whenever I could afford it—evening classes at Gotham Writers Workshop, NYU, the YMCA, summer classes at the Iowa Writers Workshop and Tin House. I wrote essays, short stories and poems and I submitted them relentlessly, collecting rejections in a pile in my desk drawer. I will never forget my first essay acceptance from The Christian Science Monitor, the joy at seeing my words in a newspaper. I continued to have hits here and there, a poem, a short story, an essay. But nothing major, nothing that could pay the bills or that made me feel like a writer.

I was losing heart. Maybe the naysayers were right after all. I would never be able to master the intricacies of the language enough to tell stories in English. And then a miracle happened—I received a fellowship from the Massachusetts Council of the Arts for a novel I was working on. Along with the financial reward, the recognition gave me the confidence boost I needed. I pushed hard to finish and revised it a couple of times before sending it out to agents. One by one they all turned it down. But I’d learned a lot working on it and when I had another idea, I knew what to do. That second book became my debut novel, Her Daughter’s Mother.

—

Daniela Petrova grew up behind the Iron Curtain in Sofia, Bulgaria. She came to the US in her early twenties and earned a BA in Philosophy from Columbia University and an MA in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness from New York University. She is a recipient of an Artist Fellowship in Writing from the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Her stories, poems and essays have appeared in many publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Salon, and Marie Claire. Her first novel, Her Daughter’s Mother, is forthcoming from Putnam in June 2019. She lives and writes in New York City.

Follow her on Twitter @DanielaGPetrova

Find out more about Daniella on her website https://www.danielapetrova.com/

About HER DAUGHTER’S MOTHER

She befriended the one woman she was never supposed to meet. Now she’s the key suspect in her disappearance.

She befriended the one woman she was never supposed to meet. Now she’s the key suspect in her disappearance.

For fans of The Girl On the Train and The Wife Between Us comes a gripping psychological suspense debut about two strangers, one incredible connection, and the steep price of obsession.

Lana Stone has never considered herself a stalker—until the night she impulsively follows a familiar face through the streets of New York’s Upper West Side. Her target? The “anonymous” egg donor she’d selected through an agency, the one who’s making motherhood possible for her. Hungry to learn more about her, Lana plans only to watch her from a distance. But when circumstances bring them face-to-face, an unexpected friendship is born.

Katya, a student at Columbia, is the yin to Lana’s yang, an impulsive free spirit who lives life at the edge. And for pragmatic Lana, she’s a breath of fresh air and a welcome distraction from her painful breakup with her baby’s father. Then, just as suddenly as Katya entered Lana’s life, she disappears–and Lana might have been the last person to see her before she went missing. Determined to find out what became of the woman to whom she owes so much, Lana digs into Katya’s past, even as the police grow suspicious of her motives. But she’s unprepared for the secrets she unearths, or their power to change everything she thought she knew about those she loves best…

“Beyond the beautiful cover, Daniela Petrova’s debut novel is absolutely dreamy and suspenseful.”—O, The Oprah Magazine

“If you read one thriller this month, make it Her Daughter’s Mother.”—HelloGiggles (“Best New Books to Read in June”)

“[An] impressive debut…burning questions will keep readers on the edge of their seats…a gripping tale of the consequences of obsession. Petrova is off to a promising start.”—Publishers Weekly

“Petrova has written a consummate page-turner that also manages incredible layers of emotional depth. This is one of the year’s most provocative and eye-opening novels.”—Crime Reads

“[Her Daughter’s Mother] is ultimately rewarding…its darkness and wild resolution will appeal to many readers.”—Booklist

“[A] suspenseful, contemporary, and twisty thriller.”—Kirkus Reviews

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing