Representation in Writing – Author’s Dilemma, Author’s Responsibility

Representation in writing – author’s dilemma, author’s responsibility

Photo by Evan Michio

There is maybe no hotter topic right now for writers than the question of representation. Writers everywhere are debating whether writing characters out of one’s own ethnicity or gender might be considered wrong.

The answer isn’t so simple.

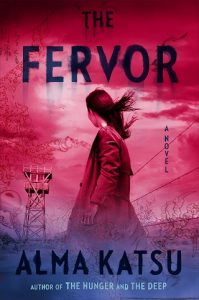

My latest novel, The Fervor (GP Putnam’s Sons) marks the first time I’ve written a main character with the same ethnicity as mine, Asian American. It’s set during the last months of WWII and mostly set in one of the internment camps. Like my previous historical horror novels, The Fervor has multiple POV characters but the main character is Meiko Briggs, a Japanese woman who was sent by her family to America to wed a Japanese man in the Seattle area. However, she falls in love and marries that man’s friend, who is white. Then Pearl Harbor happens, the husband (who is a pilot) joins the Army Air Force, and Meiko and her child are sent to the internment camp.

I didn’t think it would be a big deal to write an Asian protagonist. Meiko was just another character, and it was my job as the author to slip into her head, as I do with all the POV characters. But it turned out to be a much more emotional experience than I anticipated.

My mother was Japanese. She married my father, who was white, when they met after the war. My mom was shaped by her experiences after the war, when strangers would say hateful things, blaming her for the war. My emotional reaction involved more than WWII, however. Being an Asian woman means navigating stereotypes and others’ assumptions, most recognizably the submissive geisha or the dangerous, sexualized dragon lady. You live under a layer of societal expectations: you’re seen as servile, meek, and accommodating.

When I first wrote Meiko’s chapters, I channeled my mother, the quintessential Japanese woman. Meiko accepted what happened to her, as did the Japanese who went obediently to the internment camps. However, it didn’t work. She was too passive to make a good leading character. As all writers know, protagonists must act. They must be changed by their ordeal or quest.

Instead of having Meiko wait for someone to rescue her, I made her the hero. As I wrote the new Meiko, I was surprised by the amount of anger she felt—and realized it was anger I’d felt at various points in my life. Anger at being told to be seen and not heard, to be grateful for what others choose to give you rather than what you deserve. Writing Meiko, I could let it out.

I suspect that Meiko’s anger will resonate with a lot of readers because there’s a lot about The Fervor that is uncannily current. COVID made us all prisoners in our own homes. New policies came out seemingly every day to control heretofore unregulated aspects of our lives. Normal was turned on its head and refuses to right itself.

My experience writing my own ethnicity was a revelation, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I think you can only write a character if you share that character’s ethnicity. Since the beginning of storytelling, writers have created characters from backgrounds different from their own, whether by ethnicity, gender, or age.

If you’re going to write characters that are outside your personal experience, however, you need to approach it from an attitude of humility. You need to guard against assuming that other people’s experiences are the same as yours. That may sound a bit simplistic, but I was surprised at some reactions I got during the writing of The Fervor. Readers assumed second-generation Japanese American characters would have Japanese given names, could wear kimonos, and exclusively practice Japanese religions. Well, no: assimilation is of paramount importance to many immigrants, and it was no different for the Japanese prior to WWII. It’s okay if you don’t know something but you can’t be blind to your assumptions. Any writer attempting to write outside their own personal experiences needs to honestly assess themselves. At some point, your instincts are likely to be wrong: are you the kind of person who is willing to repeatedly second-guess herself?

I also strongly suggest that you consider hiring a sensitivity reader, if your publisher doesn’t already include this as part of their review process. My best-known book is The Hunger, a reimagining of the story of the Donner Party. You couldn’t tell the story of the Donner Party without indigenous characters. We hired a sensitivity reader to help ensure there was nothing erroneous or offensive about the way the indigenous characters were portrayed. The sensitivity reader came back with a few surprising suggestions, for which I was extremely grateful. No author wants to insult or offend other people or to deliberately perpetuate stereotypes.

—

Alma Katsu is the award-winning author of seven novels. Her latest is The Fervor, a reimagining of the Japanese internment that Booklist called “a stunning triumph” (starred) and Library Journal called “a must read for all, not just genre fans” (starred). Red Widow, her first espionage novel, is a nominee for the Thriller Writers Award for best novel, was a NYT Editors Choice, and is in development for a TV series.

www.Almakatsubooks.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/almakatsu

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/almakatsu

THE FERVOR

The acclaimed author of the celebrated literary horror novels The Hunger and The Deep turns her psychological and supernatural eye on the horrors of the Japanese American internment camps in World War II.

The acclaimed author of the celebrated literary horror novels The Hunger and The Deep turns her psychological and supernatural eye on the horrors of the Japanese American internment camps in World War II.

1944: As World War II rages on, the threat has come to the home front. In a remote corner of Idaho, Meiko Briggs and her daughter, Aiko, are desperate to return home. Following Meiko’s husband’s enlistment as an air force pilot in the Pacific months prior, Meiko and Aiko were taken from their home in Seattle and sent to one of the internment camps in the Midwest. It didn’t matter that Aiko was American-born: They were Japanese, and therefore considered a threat by the American government.

Mother and daughter attempt to hold on to elements of their old life in the camp when a mysterious disease begins to spread among those interned. What starts as a minor cold quickly becomes spontaneous fits of violence and aggression, even death. And when a disconcerting team of doctors arrive, nearly more threatening than the illness itself, Meiko and her daughter team up with a newspaper reporter and widowed missionary to investigate, and it becomes clear to them that something more sinister is afoot, a demon from the stories of Meiko’s childhood, hell-bent on infiltrating their already strange world.

Inspired by the Japanese yokai and the jorogumo spider demon, The Fervor explores the horrors of the supernatural beyond just the threat of the occult. With a keen and prescient eye, Katsu crafts a terrifying story about the danger of demonization, a mysterious contagion, and the search to stop its spread before it’s too late. A sharp account of too-recent history, it’s a deep excavation of how we decide who gets to be human when being human matters most.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips