Researching a Book in the Time of Covid, and What I Learned

By Pamela Toler

One of the oddities of my career path as a writer of historical non-fiction is that I didn’t have the chance to do archival research for my first nine books. In some cases this was because I often had ridiculous deadlines, which did not leave time to hunker down in an archives no matter how much I might have wanted to. (I had from July 2 to October 1 to research and write the first draft of Heroines of Mercy Street. I’ll let you do the math.) At other times it was because I’ve often chosen, or been chosen by big sweeping topics, like a global history of women warriors. Such projects required me to work both deep and wide, but they didn’t include trips to archives. (Where would you even start?)

One of the oddities of my career path as a writer of historical non-fiction is that I didn’t have the chance to do archival research for my first nine books. In some cases this was because I often had ridiculous deadlines, which did not leave time to hunker down in an archives no matter how much I might have wanted to. (I had from July 2 to October 1 to research and write the first draft of Heroines of Mercy Street. I’ll let you do the math.) At other times it was because I’ve often chosen, or been chosen by big sweeping topics, like a global history of women warriors. Such projects required me to work both deep and wide, but they didn’t include trips to archives. (Where would you even start?)

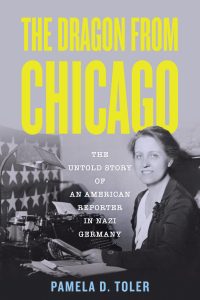

That changed with my newest book, The Dragon from Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany, which tells the story Sigrid Schultz, who was the Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune from 1925 to 1941. This was a case of no archives, no book.

I turned in my book proposal in February, 2020. In the intervening weeks, while my agent, my editor, and I went back and forth, I prepared myself for an archival dive. I sent out emails to the archives I wanted to visit. I studied the finding aid for the first archive on my list and identified the boxes of material I wanted to work with, which was thrilling. I chose a scanning app for my phone, which was not thrilling. I bought a back-up supply of mechanical pencils, also not thrilling. (Who am I kidding? Poking around in an office supply store is always thrilling.) I re-read Arlette Farge’s The Allure of the Archives and Robert Caro’s Working.

You know what happened next.

By the time I signed a contract for the book with Beacon Press in May, 2020, libraries, archives, and office supply stores were closed. My contract said the manuscript was due in two years, but none of us knew whether that was even possible. (It wasn’t.) My contacts at the archives had no idea when they would re-open, or what it would look like when they did

Unlike some of my writing friends who were at the same stage of researching and writing a book, I had two things going for me.

- I was able to access the Chicago Tribune’s historical archive on my home computer, thanks to the Chicago Public Library.

- A few days before the University of Chicago’s library shut down for the duration, an administrator in the privileges office sent an email to those of us who rent lockers warning us to come get anything we might need out of said lockers. (I suspect he wanted to me be sure no one was stuck without their laptop.) In response, I made a quick raid and checked out anything I thought I might want or need.

Better than nothing, I thought, and grumpily settled in to work with what I had.

In fact, the combination turned out to be a good place to start my research.

By the time the Wisconsin Historical Society, which held Sigrid Schultz’s papers, opened again for limited hours in August, 2020, I had worked my way through most of her by-lined articles in the Tribune. Reading my way through her work taught me a lot about the types of stories she reported, how they changed over time, and the way she used language. It sent me down fascinating rabbit holes that gave me a more complex sense of her world. Most importantly, it felt like I was following the rise of the Nazis in real time. It was chilling and fascinating.

By the time the Robert McCormick/Tribune archives finally opened in September of 1921, I was deep into what felt like a DIY master’s program, studying the history of American journalism, the rise and fall of the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany, and World War II.

***

Thanks to Covid, my experience of working in the archives, once I got there, was not what I imagined. Because I could not be sure whether the archives would close again, I did not have the luxury of thinking about what I was finding. Instead I scanned as many documents as I could each day, building an index as I went so I could find them again. The real archival work came later in my office, when I worked my way through the documents I had scanned, viewing them through the lens of what I had learned.

It turned out that it didn’t matter where I started. Each step of the research process informed the next. That’s the way it works.

—

Armed with a PhD in history, a well-thumbed deck of library cards, and a large bump of curiosity, author, speaker, and historian, Pamela D. Toler goes beyond the familiar boundaries of American history to tell stories from other parts of the world as well as history from the other side of the battlefield, the gender line, or the color bar. Toler is the author of ten books of popular history for children and adults, including most recently The Dragon From Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany. Read more about Toler and her work at www.pameladtoler.com.

The Dragon From Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany

At a time when women reporters rarely wrote front-page stories and her male colleagues saw a powerful unmarried woman as a “freak,” Sigrid Schultz served as the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief and primary foreign correspondent for Central Europe from 1925 to January 1941. Schultz witnessed Hitler’s climb to power and was one of the first reporters—male or female—to warn American readers of the growing threat of the Nazi regime in Germany.

At a time when women reporters rarely wrote front-page stories and her male colleagues saw a powerful unmarried woman as a “freak,” Sigrid Schultz served as the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief and primary foreign correspondent for Central Europe from 1925 to January 1941. Schultz witnessed Hitler’s climb to power and was one of the first reporters—male or female—to warn American readers of the growing threat of the Nazi regime in Germany.

In The Dragon from Chicago, historian Pamela D. Toler draws on extensive archival research to unearth the largely forgotten story of Schultz’s years courageously reporting the news from Berlin, from the revolts of 1919 through the Nazi rise to power and Allied air raids over Berlin in 1941. Plunging the reader into the details of a foreign correspondent’s life—the midnight cables to America, the importance of sifting facts from propaganda, Nazi attempts to control the foreign press through bribes and threats, and the constant calculations about how to get accurate information out without being kicked out of the country—Toler uses Schultz’s words to show us how the era felt as it unfolded. For example, writing of the bullying presence of Hitler’s Brownshirts inside the opening of the Reichstag in 1930, Schultz noted how motley they were; each of the Hitlerite deputies had created their own rag-tag and homemade version of the brown-shirt style.

Ultimately, Schultz’s coverage told American readers not only what the Nazis did but how they misreported the news to their own people. Her story is a powerful example for how we can reclaim truth in an era marked by the spread of disinformation and propaganda spawned by hate.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips