Researching Kipling and his Sister

I loved everything about the research for Kipling & Trix: old letters in archives, childhood photographs, biographies, memoirs, histories of the Boer War—but most of all I loved the license to roam. Not just permission but an absolute demand for travel, tracing lives passed between India and Britain. For it was my plan to follow the facts of these lives very closely while presenting them in the form of fiction. I simply had to get up from my chair, turn my back on the desk and leave my everyday world.

His wife used to say Rudyard Kipling had ‘go-fever’: he travelled all over the globe. And I was to make many happy journeys in pursuit. Trix’s life was more circumscribed. Spending a night in the Edinburgh house, now a hotel, where she lived from the 1920’s till after the war, was the boldest physical adventure she inspired. But in the case of her brother it was different.

Years before, I’d written a book about images of Cleopatra. That took me to Egypt, Venice, Ulm. But now I had a new focus for my imagination : South Africa at the time of the Boer War. The Anglo-Boer War as it’s known in South Africa today: an important difference, as you will see, for it points out that there were two sides to that conflict, two different angles you might view it from.

Some of Kipling’s most intense experience took place in South Africa. This may surprise you, for it’s India we link with him. In fact, as I discovered, Bombay, where he was born and Cape Town, where he took root at the time of the Boer War, are about level on the map. Would the climate of one have brought back the childhood experienced in the other, I came to wonder? He had been happy in Bombay as a child and the time in Cape Town seemed to have a strangely healing effect on him, though he’d been in a dreadful state when he arrived.

But that question came to me only after I’d really dug into trying to share Kipling’s physical, embodied experience, trying to know, through the pores of my skin, what he knew. That meant taking a bit of a risk now and then.

When I told friends in Cape Town that I was planning to take the overnight train up to Bloemfontein, the old capital of the Orange Free State, one of the two former Boer republics, friends looked worried. There was then and I imagine there remains, even outside notoriously dangerous cities, a low-level sense of fear among white people, one that’s bound up with mistrust of their black neighbours. I might be putting myself at risk, I was told.

But I just had to do it. Though he was internationally famous, Kipling travelled up to Bloemfontein to help set up a newspaper for the troops early in 1900. It was a critical moment in his life—struggling after the death of his 6 year old daughter which had overwhelmed him with grief the year before at a time when he himself had very nearly died too, from pneumonia. But among new friends, working together with these journalists on a paper they christened The Friend, he began to revive. At least that’s how I read the evidence of his letters.

To write about this episode I wanted to put myself through that rail journey up from the Cape at precisely that same time of year. (Only in imagination could I share his experience of travelling back with the wounded on a hospital train.)From first light I sat cross-legged on my bunk, doggedly making notes on the odd burst of butterflies, the irregular outcrop of a kopje, the scents of the veld drifting through the open window.

My arrival was not so exalting. Mindful of all the warnings, at Bloemfontein I went into the station booking office and enquired where I could find a ‘safe’ taxi. ‘We couldn’t tell you ma’am’ came the sobering reply. Nonplussed, I decided to be brazen. I went up to a group of people getting into a private car and put the same question. You can trust South African generosity. They dropped me off at my hotel: I’d simply bought into white fears but I was truly grateful

The next day however, on a visit to the Anglo-Boer War Museum, outside the town, my feelings were more complex. A friend who’d grown up in Bloemfontein, BFT as it’s known locally, had described how every year schoolchildren were marched out to the monument by the museum: a memorial to the Boer women and children who died in the concentration camps set up by the British.

Now the responsibility of my country for those deaths hit me in the chest as I confronted the numbers. It is on record that 4,177 women and 22,074 children under sixteen died in those camps. Old men died too, 1, 676 of them too old to go out on commando. Still today, as I write, remembering the bleak schedules of meagre and inappropriate rations, the photographs of gaunt children and desperate mothers,tears come to my eyes.

I felt horribly conspicuous, standing there, British all over, pale and dwarfish among the tall bronzed Afrikaaners. But I could not, simply could not, shirk the Visitors’ Book. I wrote honestly and in deep shame ‘I came to learn’.

—

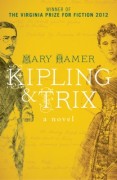

Mary was educated at the Catholic grammar school and at Oxford but she grew up a secret rebel. Kipling’s Jungle Book taught her that there was a different, more exciting way to see the world. After reading English at Oxford she taught for many years and published works of non-fiction. Eight years ago she began to research the dangerous lives of Rudyard Kipling and his sister, Trix. Only fiction could do justice to their story. Her first novel Kipling & Trix won the Virginia Prize for Fiction.

Kipling and Trix is available on amazon.

Find more about Mary on her website www.mary-hamer.com , follow her on twitter @mary_hamer or visit her on facebook.

Category: Being a Writer, Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Mary, I love, love, loved your article about your journey writing about Kipling. I just finished a biography on Stella Adler and I wish I’d had the funds to go to Israel (not that she spent much time there), but she did do freedom fighting work to help found the state. After reading your post, I thought you should write a memoir about your travels and discoveries, not fitting in, the disappointments, the surprises, your personal revelations. Thanks for the post!

Wow, Sheana, thank YOU! It’s so encouraging to get such a warm and vivid response, especially from another writer. I will look out for your biography. Stella Adler sounds a fascinating subject and a woman we should know about.

I am completely inspired by the way you have immersed yourself in your subject. Clearly this was a commitment of heart and soul. I congratulate you on this amazing accomplishment and look forward to becoming more familiar with your work.

Thank you Sandra: yes it was a heart and soul commitment. I dreaded exploiting tmy characters, so I did my very best to be true to what was known of their lives, then imagined how those lives would have felt.

Reading about the extent of your research and its emotional impact on you was inspiring. Your honesty in recounting the ways that you’d bought into “white fears” is laudable.

But I particularly resonated with this line in your essay: “Only fiction could do justice to their story.” As I embark on research for a novel about the life and times of Christine de Pisan, one of the earliest European women to support herself on her writing, I am inspired by your experience.

Thanks!

Thanks for your generous response, Kathleen and good luck with your Christine de Pisan project. I’ve laways anted to know more about her . . .