The Settling Earth: Emigration to New Zealand in the Nineteenth Century

Imagine packing a trunk, probably a box no higher than your knees. In it you place clothes to see you through your journey and beyond. You squeeze in sewing equipment, a few books, photographs or miniatures – all mementos of a home that you are about to leave, possibly forever. Perhaps you are able to take more belongings with you as you board the emigrant ship.

Imagine packing a trunk, probably a box no higher than your knees. In it you place clothes to see you through your journey and beyond. You squeeze in sewing equipment, a few books, photographs or miniatures – all mementos of a home that you are about to leave, possibly forever. Perhaps you are able to take more belongings with you as you board the emigrant ship.

Perhaps you can travel first class, but you still have to oversee the packing up of a house and the leaving behind of precious heirlooms that won’t survive the three-month crossing at sea. And then there’s your family, also left behind.

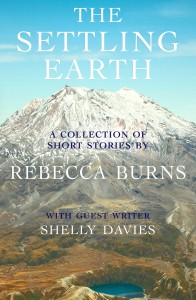

In a new collection of short stories called The Settling Earth, I fictionalise the experience of British women who, in the nineteenth century, took a leap into the unknown and emigrated to New Zealand, some eleven thousand miles away from home and all that was familiar.

The stories in The Settling Earth are a return to an area of history that I find fascinating, having studied it for many years as part of my research towards a Ph.D. I have touched and read letters and diaries by these settler women, manuscripts now safely housed in the New Zealand archives.

I have heard their voices speak again of fears, hopes, and opportunities in a strange new land. What is staggering is how many emigrants, men and women, made the decision to go – for example, in just four short years between 1875-1879, 60,000 emigrants landed in New Zealand.(1) Women emigrants travelled with husbands, fathers, brothers.

Others, in response to the reduced options open to unmarried middle-class women, travelled alone, brave and hopeful. All, however, endured the long journey at sea, discovering first-hand what one woman described as “the horrors of an Emigrant Ship […] [we are] packed in like so many cattle.”(2)

The motivating factors behind women emigrating were varied, but all who arrived in New Zealand were required to adapt and make sense of life in a new, alien land. Some women had to build their homes from scratch, cutting back dense bush and piling brick upon brick in order to put a roof above their children’s heads. For example, Sarah Higgins, who emigrated in 1842, built her own kitchen: Now I wanted a good kitchen but my husband could not leave his work to make it. He helped to mix the clay before he went to work then I got a little maid to mind the children, while I put up a mud kitchen, 20 ft. [sic] long and 12 ft. [sic] wide […] we now had a comfortable house of six rooms.(3)

Many women, of all social backgrounds, took on all manner of duties in the home. Bessie Royds, who lived on a dairy farm in Southland in 1867, spoke of being “our own dairy maid, baker, washerwoman and housemaid […].”(4)

Neighbours would often be a day’s hike away, leading to both a sense of isolation and, for some, a sense of freedom. Some embraced the opportunity to reject social customs while others, who found themselves in one of New Zealand’s small, provincial towns, discovered geographical pockets where rules of feminine decorum and constraints on behaviour remained prevalent, despite the incongruity with the harsh realities of their surroundings.

The stories in The Settling Earth portray, though fiction, the experiences of different women who made New Zealand their home. Women were vital to the British imperial mission, with their image being used in colonial propaganda as a virtuous, civilising force. Yet the position of emigrant women was more complex than propaganda allowed.

The stories in The Settling Earth portray, though fiction, the experiences of different women who made New Zealand their home. Women were vital to the British imperial mission, with their image being used in colonial propaganda as a virtuous, civilising force. Yet the position of emigrant women was more complex than propaganda allowed.

Sexuality could, as in Britain, be turned into a commodity – alongside a buttoned-up, socially codified representation of the female body, prostitution and relaxed sexual attitudes also existed. The Settling Earth imagines the lives of settler women, seeking to determine a new identity for themselves, be it an identity that embraced freedom from a scrutinising British society, or a life that continued to bow to ingrained, cultural expectations.

Of course, colonialisation drastically affected the indigenous population and, in New Zealand, settler interactions with Maori had varied outcomes. Cultural differences and skirmishes over land led to a series of wars in the 1860s and it was important to include a Maori voice in The Settling Earth. I am delighted that Shelly Davis, Maori poet and short story writer, contributed a story to the collection, giving a glimpse into the response of a Maori character to the arrival of European settlers.

[1] Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand (London: Penguin Books, 1959, 1980), p. 156

[2] Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. MS Papers 1192. Diary of Emma Hodder, p. 1. Entry dated July 1 1869.

[3] Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. MS Papers 1146, Sarah Higgins – Autobiography. Typescript

[4] Cited in My Hand Will Write What My Hand Dictates, ed. Frances Porter and Catherine Macdonald (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996), p. 286. Letter dated Oct 17 1867.

—

Rebecca Burns is an award-winning writer of short stories, over thirty of which have been published online or in print. She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2011, winner of the Fowey Festival of Words and Music Short Story Competition in 2013 (and runner-up in 2014), and has been profiled as part of the University of Leicester’s “Grassroutes Project”—a project that showcases the 50 best transcultural writers in the county.

The Settling Earth is her second collection of short stories. Her debut collection, Catching the Barramundi, was published in 2012—also by Odyssey Books—and was longlisted for the Edge Hill Award in 2013.

Follow Rebecca on twitter: @Bekki66

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Hi Jessica – thanks for the message and great to hear you’re going to read “The Settling Earth”. Your family history sounds fascinating – lots of Scots emigrated to NZ in the nineteenth century and, like many settlers, their stories are very interesting. Hope you enjoy the book and thanks for getting in touch!

I’ve ordered your book Rebecca, and I’m looking forward to reading it. My great-grandparents emigrated to New Zealand from Scotland in the 1880s. I have my great grandfather’s letters and initially they were full of hope. He was a successful barrister but was admitted to a public lunatic asylum near Wellington because of his increasingly odd behaviour.