Should You Rely On Memory?

When you’ve known a secret family story for four decades and you decide to transform the narrative into a historical novel, the big question is how much should you rely on memory and how much on documented research?

When you’ve known a secret family story for four decades and you decide to transform the narrative into a historical novel, the big question is how much should you rely on memory and how much on documented research?

In my case, the story my father told me was about our family’s original home in Nesvicz, a tiny village on the Polish-Russian border. After the Russian revolution, my 17-year old father, the eldest son, was sent to Canada. He was to prepare the way for the rest of the family, my grandparents and his seven siblings who wished to escape the tumult of Eastern Europe.

Although I’ve mulled over the story for forty years and still keep a silver-framed photograph of the original Nesvicz family in my writing room, I was hesitant to explore all the implications of their undoing in Russia. What I did discover was that my father’s two oldest brothers were slaughtered in pogroms, when Russian Cossacks rode into tiny Jewish villages and cut down every young man they could find.

I wasn’t eager to discover why my father, who was a difficult man, came to be associated with the Communist Party in Canada or what he’d done, possibly illegal, during World War II when the Communist Party was outlawed in Canada.

How to find the best way to construct a narrative that was both sensitive to my father’s version of reality, and also the recorded history that surrounded his experience, became a five-year quest for me. I knew it would be unlike anything I’d written before and entirely different from my first novel, The Cook’s Temptation (Mosaic Press, 2013), also a historical, but based on imaginary characters set in nineteenth century in England.

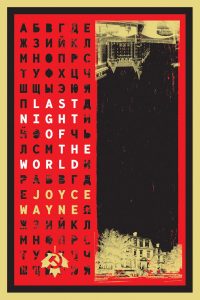

When I first began working on Last Night of the World (Mosaic Press, 2018), I’d just finished correcting the page proofs for my first novel. There, the main protagonist Cordelia Tilley is fictional so my research into provincial Victorian timelines, manners and conflicts took center stage to the development of the novel.

With Last Night of the World, the situation was different. Most of the characters are based on real-life people who lived in Canada, the Soviet Union or Britain during World War II. Their lives, everyone from a Prime Minister, to double agent Kim Philby, were all characters my father described to me.

My father was involved in politics during the time when the Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko’s defected to Canada. He knew intimately how the cipher clerk carried out his defection in 1945, stealing more than 200-pages of highly classified ciphers from the Soviet embassy in Ottawa. The documents revealed that the Soviets were spying on nuclear developments in North America. Moscow’s intent was to steal the formula for the atomic bomb, the very one invented by the scientists at the Manhattan Project located in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Ultimately there was my father’s story –he also became a character in the novel—and the view of many Cold War historians, along with the de-classified intelligence reports that I requested from the FBI and MI6. All the players my father spoke about accrued lengthy intelligence files, not the smallest by any means being the comments about Freda Linton, the main character in Last Night of the World.

How was I to stay true to fact while writing a historical espionage thriller? How to connect the story of my family from the little village of Nesvicz to world shattering events? In my heart and mind, I needed to find a way to resolve the fact that my fathers’ colleagues spied for the Soviets and were guilty of treason, while insisting in the novel that these characters remain human, vulnerable and to some extent worthy of certain degree of compassion.

What I learned, was that I shouldn’t judge. I am not a historian, I told myself over and over again. My work was to bring the story and the characters to life, not to decide who was on the right side of history.

As Sandra Gulland, the author of the trilogy of novels based on the life of Josephine Bonaparte: The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B.; Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe; The Last Great Dance on Earth, recently remarked: “It’s important to stick to the facts — to know the facts — but it’s even more important to tell a compelling story.”

My process was to follow my intuition, and harder still, to believe in myself. That takes courage, the kind of courage that most writers, women writers in particular, are not accustomed to using. As women, we’re taught to compromise and not to offend, but while I worked on successive drafts of the narrative, I began to see things differently. The easy way out was for me to strictly follow the facts. To be the obedient student of history. Yet I came to sympathize with my female spy Freda Linton and her fight to survive as a “honey trap” during the tumultuous years between the beginning of the Great Depression and the end of WWII.

No amount of intelligence reports or historical coverage could tell me why she chose to become a spy for the Soviets, engaged in activities that female agents must do. By veering from the strict facts, I created a character that made emotional sense and was not just a mouthpiece for a slice of history.

In a letter, a columnist for the Toronto Star who attended the book launch for Last Night of the World wrote: “I was very touched by the way you presented things at your launch. Really humane, like saying the people you wrote about were naive, came from remote villages, and didn’t know the language. It put a human quality on all of it, that anyone can identify with.”

When I received this letter, I knew I’d accomplished what I’d set out to do. That is, not to allow the historical record to corner me into makings judgment calls that fiction writers need not make. Our job is to make historical characters so real to the reader that they come to understand their humanity, their indecisions, their triumphs and their deadly mistakes.

After all, isn’t that what fiction is about?

—

BIO: Joyce Wayne was born in Windsor, across the border from Detroit. While doing a graduate degree in English literature in Ottawa she was party to stories about the Soviet Embassy cypher clerk, Igor Gouzenko, and how his defection to Canada in 1945 was the spark that launched the Cold War. Joyce’s career began in book publishing in Toronto where she worked as the staff writer at Quill & Quire, the magazine for the book industry in Canada. She was also the editorial director of non-fiction at McClelland & Stewart Publishers. For twenty-five years, she was the head of the Journalism Department at Sheridan College in Oakville, Canada. Joyce’s debut novel, THE COOK’S TEMPTATION, was published in 2014. She lives near Toronto with her husband.

BIO: Joyce Wayne was born in Windsor, across the border from Detroit. While doing a graduate degree in English literature in Ottawa she was party to stories about the Soviet Embassy cypher clerk, Igor Gouzenko, and how his defection to Canada in 1945 was the spark that launched the Cold War. Joyce’s career began in book publishing in Toronto where she worked as the staff writer at Quill & Quire, the magazine for the book industry in Canada. She was also the editorial director of non-fiction at McClelland & Stewart Publishers. For twenty-five years, she was the head of the Journalism Department at Sheridan College in Oakville, Canada. Joyce’s debut novel, THE COOK’S TEMPTATION, was published in 2014. She lives near Toronto with her husband.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JoyceWayne1951

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/joyce.wayne

Website: http://joycewayne.com/

Book: http://www.mosaic-press.com/product/last-night-world/

LAST NIGHT OF THE WORLD

On a hot Ottawa night in August 1945, Soviet agent Freda Linton’s world is about to fall apart. She’s spent the war infiltrating the highest levels of the Canadian government as an undercover operative for the fledging Canadian Communist Party and for Moscow’s military police.

On a hot Ottawa night in August 1945, Soviet agent Freda Linton’s world is about to fall apart. She’s spent the war infiltrating the highest levels of the Canadian government as an undercover operative for the fledging Canadian Communist Party and for Moscow’s military police.

As the global conflict nears its conclusion, her Soviet embassy handler and darling of the diplomatic scene Nikolai Zabotin sends her to retrieve atomic secrets from the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories. When Freda discovers that Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko plans to turn over top secret files to the RCMP that will expose Freda and the others in her spy ring, she is faced with an impossible decision and must determine who is on her side.

Should she risk everything to smuggle out nuclear secrets that will kick off the Cold War?

Joyce Wayne’s Last Night of the World brings a high-energy creativeness and emotional tension to a story that is rooted in a generation’s defining incident.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Joyce Wayne’s book is a first for Canada as a historical-fiction novel about a Canadian Soviet spy during one of the most interesting eras in Canadian and world history. The buzz for “Last Night of the World” hasn’t stopped yet. This is a fabulous article and “Last Night of the World” is a fabulous read.

– Ivy Reiss for The Artis magazine, http://www.TheArtisMagazine.com