Sparring the Pandemic

When the bell rang, I tore loose the black Velcro straps with my teeth and pulled off my yellow leather boxing gloves. Quickly I unstrapped my padded helmet and tilted it back on my head. I wanted more air on me. Sweat streamed down my face and neck; my breath came hard and I grit my teeth. The Muay Thai workout with fighters half my age was intense and demanding. What was I doing tormenting myself with a bunch of 30-somethings?

When the bell rang, I tore loose the black Velcro straps with my teeth and pulled off my yellow leather boxing gloves. Quickly I unstrapped my padded helmet and tilted it back on my head. I wanted more air on me. Sweat streamed down my face and neck; my breath came hard and I grit my teeth. The Muay Thai workout with fighters half my age was intense and demanding. What was I doing tormenting myself with a bunch of 30-somethings?

It turns out that without knowing it, I was training in specific life skills that you need to thrive in a pandemic. In sparring, your partner assaults you with punches and kicks, while you dodge, parry, block, and counterattack. SARS-CoV-2 assaults you with threats and demands, while you execute various defensive maneuvers. But kickboxing is not only about physical training, and SARS-CoV-2 is not only about protecting ourselves. We must also master the mental game and never let ourselves become the victim. Whatever is happening, we have power.

To fight, I had to confront disruptive fear, anger, and aggression. Fear would melt my confidence. It made my training fail so I couldn’t remember what to do. Anger would distract my attention from the immediate fight dynamics. It made me misjudge what was happening and do stupid things. And there was always the foolish impulse to try to dominate the situation with cocky, undisciplined aggression. Wild power strikes rarely pay off. Rather, they open you to imbalance and counterattack. The truth is, when I step into a fight ring, the opponent I really face is myself.

Stepping into an ordinary day can feel like going over the ropes. This morning, stirring the sugar into my wife’s coffee, I fish the half-and-half carton out of the refrigerator and discover it is almost empty. I am going to have to stop at the store, and that is no longer a trivial irritation. There’s a customer wait line outside. Masks are required in our state. Once indoors, I’ll be sharing air with others. I’ll need to steer clear of people in the aisles and maintain the proper distance in line. And keep an eye out for social conflict; last week an angry person got into a confrontation with the security guard. I can use self-checkout to avoid the cashier. I’ll have to sanitize my hands before I go in and after I come out, and wash them thoroughly when I get home.

It’s not just the daily inconvenience, of course. The virus has permeated our lives. From child care and education to elder care and assisted living; from jobs and businesses to sports and recreation, we must now individually deal with poorly understood potentially life-threatening risks. Social distancing forces us to treat friendly people as if they pose a personal danger. When we most need to connect, we must put up barriers.

For four or five months, I have been socializing only over the phone and internet. Planned visits from traveling friends and family were, of course, cancelled. Now, my wife and I are trying a few virus-safe gatherings. This week our neighbors had us over for socially distanced cocktails. Three couples sat outside, seated 8-10 feet apart. We felt almost normal, having a bite to eat and drink with real people. And tonight, we are taking dinner to a friend’s house. She came home early from the hospital after hip-surgery, so her friends and family set up a visitation schedule. She is in a high-risk group. I will wear my KN95 protective particle filtering mask as we sit around her bed in the small bedroom. Windows will be closed and the air conditioning on. I will have to remove my mask to eat but we will be six feet apart.

Am I being safe and sensible? Who really understands how to defend against a tiny packet of RNA wrapped in sticky protein? Is it safe to fly? Could I drive cross-country to see my daughter? Can I visit my father-in-law in his nursing home? With all the mixed-up changing information, it’s hard to know what the right safety protocols really are.

Commonplace social cues and niceties like handshakes and smiles just aren’t there for us right now. It’s hard to relax around strangers. I’m wearing my mask when a repair person comes to look at some wiring in the house. He is not wearing a mask, though they are mandated in our state. Should I ask him to wear one when he comes in? It seems rude to press my mask around my face and back up three feet, but wasn’t it rude to show up at my home without a mask?

Differences in mask and distancing behavior are going to be with us for a while. The risk of illness, death, financial loss or career upset will continue to haunt us. How are we going to navigate all these diverse interactions and scenarios?

If there is one thing I learned from Thai kickboxing, it is that even when I am panicking, I am not helpless. Muay Thai, the Art of Eight Limbs, trained me how to deal with frightening onslaughts. When challenged, I can grab these four life skills.

Regain my composure. Sparring taught me to intentionally regain my composure. Whether triggered with fear, anger, or aggression, I bring my attention to my center and breathe. I gather my energy inside my belly. I compose myself and let my mind settle. This gives me access to all my resources so I can respond appropriately to the situation.

Handle myself. Enduring endless boxing rounds showed me no one is going to rescue me. I might be tired, distracted, crabby, or feeling cowardly, but in the ring my opponent does not care. It’s my responsibility to handle myself. There’s no point trying to blame someone for my situation. I must muster the best response I can. I am alone in there; I must take responsibility for the moment. This cold reality taught me to dig deep enough to find the courage to keep showing up. To keep showing up is a victory itself.

Always be ready. Fight training taught me to always be ready to meet unexpected challenges head on. Our coach used to call out “Fifty left, fifty right!” and we would have to execute the 100 kicks no matter what. He would stop class to wait for the last kicker to finish. You had to be ready to deal with it, and part of that attitude is keeping a balanced fighter’s stance. This starts with your ready posture and spreads to the mind. Whether it is the coach’s commands or the daily demands of social distancing, when you are always ready you can take right action and then return to a steady, balanced stance.

Fighter’s heart. Long-distance relationships. Money. Teleconferences. Boredom. Frustration. Exhaustion. Isolation. Kids. Loneliness. Fear of crowds. The need for fresh air. It’s like an onslaught of fists and shins. To the daily landscape of coronavirus insults and challenges I can bring a fighter’s heart. In the fight game, there’s no time for complaining – it drains vital energy – and there’s no quitting before the bell. When I am beaten down, bruised and hopeless – say about two minutes into a tough round– it is the moment to assert that no one owns me. No one gets to say they made me give up, not even a stupid virus. I decide when to quit. When I am at the bottom of the pit, I rise up again one more time.

Muay Thai taught me to show up ready to own challenging situations. Because I have a fighter’s heart I am not going to quit, give up, retreat, or surrender to this virus. And there’s no escape from it. We’re in the ring until the bell.

—

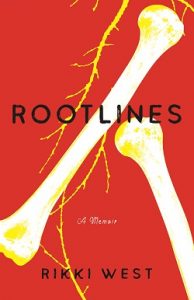

Rikki West is the author of Rootlines: A Memoir (She Writes Press, 9/22/20) about her journey with her sister to fight a devastating cancer diagnosis to become the perfect donor as one of the only stories told from the donors point of view. A student of meditation who started training in Muay Thai at age sixty-two. She holds a bachelor’s in genetics from the University of California at Berkeley and a master’s in integrative humanities from San Francisco State University.

ROOTLINES: A MEMOIR

Rikki and her sister, Linda, fell out with one another four months ago. They are not speaking when Linda emails that she has lethal abdominal tumors, that her only hope of survival is a total bone marrow replacement. Linda claims Rikki is too old to donate, and explains there’s only a slight chance she is a good match anyway―but Rikki refuses to accept that. Despite the wounding between them, Linda’s email ignites a wild aspiration in her sister: she will become the perfect donor, the perfect match, with the healthiest, most vigorous cells possible. She rises with intent to heal herself, her sister, and their rootlines, the patterns formed in their family of origin that have quietly shaped their lives.

Rikki and her sister, Linda, fell out with one another four months ago. They are not speaking when Linda emails that she has lethal abdominal tumors, that her only hope of survival is a total bone marrow replacement. Linda claims Rikki is too old to donate, and explains there’s only a slight chance she is a good match anyway―but Rikki refuses to accept that. Despite the wounding between them, Linda’s email ignites a wild aspiration in her sister: she will become the perfect donor, the perfect match, with the healthiest, most vigorous cells possible. She rises with intent to heal herself, her sister, and their rootlines, the patterns formed in their family of origin that have quietly shaped their lives.

Rikki walks through the science while confronting dogma that limits how mind can transform body. She builds herself into a stem cell factory using Muay Thai kickboxing and vegetarian nutrition. Working through childhood wounds and mental limits with meditation and yoga, she finds her own power, as well as ways to show up for Linda and walk with her from the edge of death to a new life. Together, the two sisters beat the lymphoma―and, as they rediscover the intimacy and love of their innocent childhood, heal the intertwined roots of their family pain.

Category: On Writing