Love Female Characters in Crime fiction? Thank the History of Women in Noir

G rief takes people in different ways. Mrs. Allynson’s had moved her to change her chalk-stripe costume for a soft, blue housedress that fitted in her waist, fell loose along her arms and clung from her hips down. The blue was livened by a string of cut stones of a lighter shade, a dark silk flower pinned high on a mandarin collar, high-heeled matching slippers, straight seams and a scent of jasmine blossom in her hair. We didn’t speak. She seemed a little out of joint. Following close behind her to the top of the stair was work you don’t expect to get paid for.

rief takes people in different ways. Mrs. Allynson’s had moved her to change her chalk-stripe costume for a soft, blue housedress that fitted in her waist, fell loose along her arms and clung from her hips down. The blue was livened by a string of cut stones of a lighter shade, a dark silk flower pinned high on a mandarin collar, high-heeled matching slippers, straight seams and a scent of jasmine blossom in her hair. We didn’t speak. She seemed a little out of joint. Following close behind her to the top of the stair was work you don’t expect to get paid for.

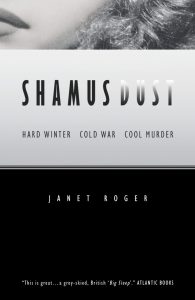

That’s Newman, the shamus in Shamus Dust, contemplating the recent widow of a client’s lawyer. Shamus Dust, in its way, is an elegy for noir as I understand it. The recent widow follows on a long line of women in noir. To explain how the line came about, let me start with a story.

First an admission. I’m a museum hound, but also a relative newcomer to American history, so the museums that tell it are apt to intrigue. For instance, the Minnesota History Center in Saint Paul. You see, it has a sign in the foyer, pointed at a gallery, that says: Minnesota’s Greatest Generation. Now which generation in the world do you think that might that be? I guessed at pioneer tales of the midwest, or perhaps of harnessing the giant Mississippi (thrilling – there are no rivers in my country, or even a year-round stream). I licked my lips like a kid in a candy store, took the stairs and couldn’t have been more wrong. The story is strictly twentieth century.

For the Minnesota History Center, its greatest generation was born in the shadow of the Great War. Raised through the pit of the Great Depression. It was in its teens through the New Deal and the Dust Bowl years and then, when the very hardest times began easing, it learned for the first time where Pearl Harbor was. So it upped and migrated to find war production work. Fought across oceans.

And four years later those who came back braced for A-bombs, the Cold War and Korea. Any one of those upheavals would have left its mark. The women and the men we’re talking about had run the gamut by the time they were in their thirties. Why remind you of their story? Because they were the audience ready-made for noir. And they found it at the movies.

Film noir? It was a phenomenon that sparked almost magically in Hollywood in the midst of the Second World War, in studios short on resources but long on talent. The spark was fanned by a wave of European refugee film-makers, schooled in a startling, expressionist cinema of careening angles, terse lighting and dense shadows. And it set alight some of the studios’ most bankable contract stars, losing interest in their regular Happy Ever After fare just as much as their audiences were. Enter a Hollywood era ready and able to make movies for dark, disillusioned times.

For women in noir, this is where it starts, in a stunning decade and more of film-making that ran on through the end of the studio system.

The forerunners of these movies fill walls in film institute libraries. But we’ll cut to the chase. When Paramount bought the rights to a long short story by James M. Cain, it was transformed into a 1944 film masterpiece. Billy Wilder directed. He brought in Raymond Chandler, no less, to share the screenwriting. The experimental, claustrophobic photography is John Seitz. But since it’s the women in noir we’re here for, our special interest in Double Indemnity is the casting.

Cain’s is an everyday, based-on-a-true-crime tale of clear-eyed, suburban lust, complicity, murder and life insurance. Wilder had the call on casting. His was the striking idea of persuading Fred MacMurray to play against type as insurance salesman Walter Neff. For the hardshell wife who seduces him to chalk off her older husband, he went to Barbara Stanwyck. In 1944, stars didn’t come bigger. In that year MacMurray was the highest earning star in Hollywood.

Stanwyck was a screen goddess supreme, not only top earning actress, but the highest paid woman in America. She was also well aware that the role of unredeemed, clear-eyed, corrupt and sexually incandescent manipulator Phyllis Dietrichson, might not be altogether best for her image.

Yet she let herself be persuaded (eased by a $100,000 paycheck equal to MacMurray’s). The performances were electric. The result, a fearless original. Double Indemnity became a box office and critical triumph. More important, Miss Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson blazed a trail; the start of a line of magnetic, subversive, illusion-free and armor-plated women who chimed perfectly for movie audiences right through the early Cold War.

That era of noir got overtaken, naturally enough, along with the generation it was made for. But it cast a shadow that reaches down to us today. For the fact is, these are the movies that showed how to write rounded, smart, convincing women who could also be as dark and transgressive as their times or any of the men around them. And once out of the box, there’s been no putting them back. You’ll have your own favorites in current crime fiction. But with times darkening again, it can be fascinating – also a lot of fun – to rediscover the originals, and be reminded of the period they sprung from.

—

JANET ROGER: Janet is a writer and an avid fan of film noirs, those movies first crafted in Hollywood that span a golden decade from the mid-1940s. She calls film noir the “ground-breaking cinema of its time, peopled with an unforgettable cast of the era’s seen-it-all survivors, slick grifters, racketeers, the opulent and the corrupt.”

She’s fascinated by the period, the generation that came through it, and the hardboiled detective fiction it inspired. SHAMUS DUST is her homage.

Outside of writing, and life on a small island off the coast of Africa, she seeks out English-language bookstores wherever she goes.

The audiobook for SHAMUS DUST proudly features the vocal talents of John Reilly (CBS Radio, The Disney Channel), whose reading captures the noir mood and rhythms beautifully. To learn more about SHAMUS DUST and Janet Roger, visit https://www.shamusdust.com/.

SHAMUS DUST

Two candles flaring at a Christmas crib. A nurse who steps inside a church to light them. A gunshot emptied in a man’s head in the creaking stillness before dawn, that the nurse says she didn’t hear. It’s 1947 in the snowbound, war-scarred City of London, where Pandora’s Box just got opened in the ruins, City Police has a vice killing on its hands, and a spooked councilor hires a shamus to help spare his blushes. Like the Buddha says, everything is connected. So it all can be explained. But that’s a little cryptic when you happen to be the shamus, and you’re standing over a corpse.

Two candles flaring at a Christmas crib. A nurse who steps inside a church to light them. A gunshot emptied in a man’s head in the creaking stillness before dawn, that the nurse says she didn’t hear. It’s 1947 in the snowbound, war-scarred City of London, where Pandora’s Box just got opened in the ruins, City Police has a vice killing on its hands, and a spooked councilor hires a shamus to help spare his blushes. Like the Buddha says, everything is connected. So it all can be explained. But that’s a little cryptic when you happen to be the shamus, and you’re standing over a corpse.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips