The Berlin Letters by Katherine Reay, Excerpt

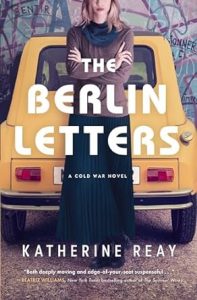

THE BERLIN LETTERS

Bestselling author Katherine Reay returns with an unforgettable tale of the Cold War and a CIA code breaker who risks everything to free her father from an East German prison.

Bestselling author Katherine Reay returns with an unforgettable tale of the Cold War and a CIA code breaker who risks everything to free her father from an East German prison.

From the time she was a young girl, Luisa Voekler has loved solving puzzles and cracking codes. Brilliant and logical, she’s expected to quickly climb the career ladder at the CIA. But while her coworkers have moved on to thrilling Cold War assignments—especially in the exhilarating era of the late 1980s—Luisa’s work remains stuck in the past decoding messages from World War II.

Journalist Haris Voekler grew up a proud East Berliner. But as his eyes open to the realities of postwar East Germany, he realizes that the Soviet promises of a better future are not coming to fruition. After the Berlin Wall goes up, Haris finds himself separated from his young daughter and all alone after his wife dies. There’s only one way to reach his family—by sending coded letters to his father-in-law who lives on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

When Luisa Voekler discovers a secret cache of letters written by the father she has long presumed dead, she learns the truth about her grandfather’s work, her father’s identity, and why she has never progressed in her career. With little more than a rudimentary plan and hope, she journeys to Berlin and risks everything to free her father and get him out of East Berlin alive.

As Luisa and Haris take turns telling their stories, events speed toward one of the twentieth century’s most dramatic moments—the fall of the Berlin Wall and that night’s promise of freedom, truth, and reconciliation for those who lived, for twenty-eight years, behind the bleak shadow of the Iron Curtain’s most iconic symbol.

We are delighted to feature this excerpt!

Chapter 1

Luisa Voekler

Arlington, Virginia

Friday, November 3, 1989

While seemingly complex, codes, ciphers, cryptograms, or whatever you choose to call them, are deceptively simple. Once you crack them.

In reality, only a few in the history of code breaking—at least that I’m aware of—were truly ingenious. The Enigma cipher? Undeniably impressive. It had billions of permutations. Thank goodness there was a brain like Alan Turing’s around. The Great Cipher, or Grand Chiffre, was also brilliant. But it was too unwieldy to be truly utilized. It employed fourteen hundred numbers that meant all sorts of different things—words, phrases, or even references to other codes. But if one can’t use it, how brilliant is it? I mean, who is going to lug a huge book around to translate a Grand Chiffre code? No one on a field of battle, that’s for certain.

So for ease of transmission and translation, most ciphers are based upon some form of shift, substitution, or transposition. Furthermore, a coder rarely varies his or her approach. I suppose that’s a bit of hubris on their part, or they simply do what they know best. But it does mean that once you crack a coder’s go-to method, you’ve got them. Their codes unfold easily and then you get a nod from your boss and a round of celebratory drinks with your coworkers at a Friday happy hour.

At least that’s how it works for those of us on Venona II.

No one outside this office knows about Venona II. Heck, the first Venona Project, which ended nine years ago, is still classified and will remain so for the foreseeable future. We were only briefed on it because we are picking up where those brilliant women left off. After thirty-seven years of deciphering Soviet codes from World War II into the early Cold War, the Venona Project shut down and its record became the stuff of lore. It’s truly impressive—they discovered Kim Philby, Klaus Fuchs, Soviet infiltration of the Manhattan Project, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and so much more.

We only hope we can do so well.

Four of us analysts are on Venona II, and everyone—excluding me—works on Cold War codes. I’m still stuck on World War II. Not that it’s a status thing to move on to the next “war.” It just feels to me like World War II has been covered. If those smart Venona Project women didn’t uncover it already, can it really be that valuable? Or relevant any longer? Yet it undeniably is, so I spend my days on Third Reich ciphers spanning from 1939 to 1945. And I shouldn’t complain. Just this summer I unlocked the names of two previously unknown Nazi guards from Auschwitz, and both are now poised to stand trial for “accessory to murder” for 200,000 and 180,000 deaths respectively.

It’s those victories, along with some impressive finds during the early Cold War era, that keep CIA Deputy Director of Analysis Andrew Cademan funding Venona II as a small line item on a hidden budget sheet in an off-site office. We have to be off-budget and off-site because, just like the original Venona Project, we sometimes uncover a few of our own turned traitor. That’s a dark day around here and, unfortunately, there have been a few of them.

“We matter,” Andrew says at almost every weekly meeting. “Our wins and the accountability we provide matters.”

That said, working here is not where I expected to be, and sitting at a desk basically solving puzzles is not what I expected to be doing. Not by a long shot. After college, when I took the Foreign Service Officer Test and applied to the CIA, I aimed to be an agent, an operative under nonofficial cover if I proved so worthy. It was a leap, but it was the dream too. Granted, my desires probably outstretched my skills, especially after consuming a steady diet of John le Carré books, old episodes of The Avengers, and James Bond movies throughout my teenage years. But I was so sure I could cut it, that I wanted that life, and that I could keep all those secrets safe while doing good in the world, that I experienced a bit of tunnel vision.

I got in. I got close. Then one day, I got cut. I made it all the way to covert training at the Farm, and I didn’t lose my asset, I didn’t shoot a civilian in a fictional village or in simulated attack, and I didn’t do anything wrong that I could discern. I simply got called into the field operator’s office and was reassigned to Andrew Cademan’s division, at first in budgeting no less, with no explanation given. No one gives or gets those in the CIA.

That was the hardest part. Not knowing what I’d done wrong.

That’s not true. The hardest part was the pitying looks, comments, and hugs my peers gave me as I packed my duffel. Every person in my class wanted to know what happened, and when I couldn’t tell them, they acted like I’d caught a contagious virus. They offered their tepid condolences while backpedaling lest they catch it too.

Only Daniel Rudd gave a crap. Only Daniel pursued me to talk, digest, even rage if I wanted to. But I didn’t want to be pursued. I wanted to hide away, lick my wounds, and forget I ever tried to reach so high. After a month, he gave up and simply vanished.

I worked five years in budget analysis for another of Andrew’s groups until he started Venona II a little over two years ago. While I don’t miss calculating and reconciling costs, I am a little tired of sitting at a desk and culling through the past with a fine-tooth comb and a microscope.

I—

I need to stop complaining . . .

BUY HERE

Katherine Reay is a national bestselling and award-winning author of several novels and one work of nonfiction.

Katherine Reay is a national bestselling and award-winning author of several novels and one work of nonfiction.

For her fiction, Katherine writes love letters to books, and her novels are saturated with what she calls the “world of books.” They are character driven stories that examine the past as a way to find one’s best way forward. In the words of The Bronte Plot’s Lucy Alling, Katherine writes of “that time when you don’t know where you’ll be, but you can’t stay as you are.”

Katherine holds a BA and MS from Northwestern University, and after several moves across the globe, lives outside Chicago.

Please visit Katherine on social media, on FB at Katherinereaybooks, Instagram @katherinereay, or visit her website at www.katherinereay.com

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing