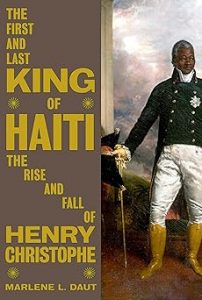

The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe by Marlene L. Daut : Excerpt

The essential biography of the controversial revolutionary and only king of Haiti. Henry Christophe (1767 – 1820) is one of the most richly complex figures in the history of the Americas, and was, in his time, popular and famous the world over. In The First and Last King of Haiti, a brilliant, award-winning Yale scholar unravels the still controversial enigma that he was.

The essential biography of the controversial revolutionary and only king of Haiti. Henry Christophe (1767 – 1820) is one of the most richly complex figures in the history of the Americas, and was, in his time, popular and famous the world over. In The First and Last King of Haiti, a brilliant, award-winning Yale scholar unravels the still controversial enigma that he was.

Slave, revolutionary, king, Henry Christophe was, in his time, popular and famous the world over. Born to an enslaved mother on the Caribbean island of Grenada, Christophe first fought to overthrow the British in North America, before helping his fellow enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue, as Haiti was then called, to end slavery. Yet in an incredible twist of fate, Christophe began fighting with Napoleon’s forces against the formerly enslaved men and women he had once fought alongside. Later, reuniting with those he had abandoned, he offered to lead them and made himself their king. But it all came to a sudden and tragic end when Christophe—after nine years of his rule as King Henry I—shot himself in the heart, some say with a silver bullet.

But why did Christophe turn his back on Toussaint Louverture and the very revolution with which his name is so indelibly associated? How did it come to pass that Christophe found himself accused of participating in the plot to assassinate Haiti’s first ruler, Dessalines? And what caused Haiti to eventually split into two countries, one ruled by Christophe in the north and the other led by President Pétion in the south?

Drawing from a trove of previously overlooked sources to paint a captivating history of his life and the awe-inspiring kingdom he built, Marlene L. Daut offers a fresh perspective on a figure long overshadowed by caricature and cliché. Peeling back the layers of myth and misconception reveals a man driven by both noble ideals and profound flaws, as unforgettable as he is enigmatic. More than just a biography, The First and Last King of Haiti is a masterful exploration of power, ambition, and the human spirit. From his pivotal role in the Haitian Revolution to his coronation as king and eventual demise, this book is testament to the enduring allure of those who dare to defy the odds and shape the course of nations.

The First and Last King of Haiti is a riveting story of not only geopolitical clashes on a grand scale but also of friendship and loyalty, treachery and betrayal, heroism and strife in an era of revolutionary upheaval.

Adapted from The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe © 2025 by Marlene L. Daut. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The work of preparing the renamed capital city, Cap-Henry, for President Christophe to become King Henry happened within the astonishing space of just two months. On March 26, 1811, Christophe issued a proclamation announcing that his council of state had just promoted him from the position of president of the State of Haiti to king of the Kingdom of Haiti. Just one week later, another edict announced the creation of the nobility, with Christophe’s most cherished friends and administrators among the hundreds of dukes, counts, barons, and chevaliers named to the royal order of Saint Henry.

For the coronation, which took place on the Champ de Mars of Cap Henry, the country’s builders erected a temporary church. Two hundred fifty feet long and just as wide, the interior of the edifice was divided into nine arcades. In the center stood an eighty-foot-high cupola, in the middle of which sat the king’s throne. A design feat fit to rival that of any of old Europe’s creations, the seventy-foot-tall throne was positioned under a “superb baldachin” of crimson silk. Embroidered in gold and adorned with gold fringes, the opulent and oversized chair had been studded with golden stars and phoenixes, which gave it the appearance of “rising majestically,” in the words of the ceremony’s official recorder, Julien Prévost, now the Comte de Limonade.

The interior of the church shone as well with two rows of galleries on both sides of the nave, draped entirely in silk cloth the color of celestial blue, adorned with gold fringes, and “pleasingly studded with gold stars.” Tapestries bearing the king’s coat of arms—two crowned lions holding a black flag strewn with stars and imprinted with a gold phoenix rising from flames hovering over a gold ribbon that read “I am reborn from my ashes”—covered nearly everything in the church. A large gold crown, not dissimilar to the one the king would don, hovered over a ribbon on his coat of arms bearing the words “God is my cause, and my sword.”

The twelve-foot-long altar had on its left side a large grandstand elegantly shrouded in crimson silk, fringed with gold, intended for Her Majesty, the queen, and the people of her maison, or household. The Maison de la Reine initially included Princess Jeanne, wife of the king’s nephew, the Duc de Port-Margot, and Marie-Louise’s dame d’honneur, or first lady-in-waiting. Marie-Louise’s maison also included her second lady-in waiting, Princess Noële, wife of her brother, Noël Coidavid, himself the Duc de Port-de-Paix.

The Comte de Limonade described the front of the newly built church in extravagant prose as he tried to capture the lavish eloquence of the occasion. “In front of the main facade of the church, the arms of the king were painted six feet high, surmounted by the Haitian flag, which floated in the air,” Limonade wrote. “We read these words on the sides of the galleries, ‘freedom,’ ‘independence,’ ‘honor,’ ‘Henry’!” To the right of the Champ de Mars stood the royal tent, surmounted by two flags, also bearing the arms of the king. The interior of the tent contained three chambers, separated by curtains of green taffeta, themselves gold fringed and ornamented with stars and a gold phoenix. Surrounding the interior of the tent reigned a gallery draped once more in green taffeta, in which could be seen the chiffres, or initials, of the king, the queen, the prince, and the royal princesses.

For weeks the entire city had prepared for this momentous occasion.

The streets where the royal cortege was to pass on the way to the church had been leveled, repaved, and sanded. At the center of the Place d’Armes had been erected an eighty-foot column, topped with a transparent globe, itself eight feet high, surmounted by a crown, in the middle of which again appeared the chiffres of the king, queen, prince, and royal princesses. Laurels and flowers decorated the column on all sides, one part of which read, “The King, to the Army and Navy!” The four facades of the royal palace were decorated as well, garnished with lanterns arranged to look like the royal chiffres amid yet more stars and phoenixes.

The coronation’s proceedings began several days before the king and the queen were to be crowned by Brelle in the magnificent church constructed for the occasion. On May 30, the newly designated aristocracy gathered at six in the morning in front of the church on the Champ de Mars for their official swearing-in. After the king and queen arrived, the members of the nobility—namely, the princes, dukes, ministers, counts, barons, and chevaliers—successively took the following oath: “I swear obedience to the Constitutions of the Kingdom and fidelity to the King.” After this oath, Christophe addressed the civil and military officers in a loud voice and commanded them to swear an oath:

Officers, Sous-Officers, and Soldiers, you are swearing on your honor, on what is most sacred to you, to devote yourself to the service of the Kingdom, to the preservation and integrity of its Territory, to the defense of the King and the Royal Family, of the Laws and Constitutions of the Kingdom; to maintain with all your power Liberty, Independence, and to die, if necessary, to support the Throne.

The military officers raised their right hands and swore in a unanimous voice, “I swear it.” Afterward, on the same day, the king hosted a huge reception, replete with toasts and speeches, and attended by all the new members of the aristocracy and military officers.

This ceremony particularly moved the Comte de Limonade. He could not help but marvel at the transformation of colonial Saint-Domingue into the Kingdom of Haiti. Standing in appreciative wonder, the count watched as “those illustrious and intrepid defenders of the state, those founders of the liberty and independence of their country, covered in honorable scars and wounds received in combat for the preservation of their rights, came to modestly receive from the hands of Henry, this worthy military recompense, the prize of valor awarded by the hand of the hero who himself was decorated with it, as well as his worthy and beloved son.”

BUY HERE

—

Marlene L. Daut is Professor of French, African American Studies, and History at Yale University. She is the author of The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe (Knopf, January 2024); the award-winning Awakening the Ashes: An Intellectual History of the Haitian Revolution (UNC Press, 2023); Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism (Palgrave, 2017); and Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World (Liverpool, 2015).

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing