The Research That Brought The Good Doctor Of Warsaw To Life

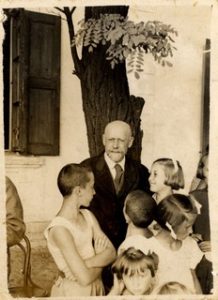

Dr Janusz Korczak

Dr Janusz Korczak was a children’s doctor and educator who lived and worked in Poland between the wars, beloved for his children’s books and his advice to parents on the Polish radio. I first came across him some 15 years ago when I heard some of his quotes at a teacher’s conference.

The wisdom of an elderly bachelor from pre-war Poland who had never had children of his own revolutionised how I approached my own children both as a mother and a teacher. He ran two orphanages for Polish and Jewish Polish children where all 200 children felt loved, known and fathered by him and he fought against the increasing tide of anti-Semitism that stained Poland and Nazi Germany.

When the Nazis invaded Poland Dr Korczak and the rest of Warsaw’s half a million Jewish people found themselves incarcerated in a square mile of slum housing with a eight-foot brick wall around it – the Warsaw ghetto. He tried to shield his 200 orphans from the horrors of the ghetto. No one believed the Nazis would touch such a famous and beloved man, but in 1942 the orphanage was raided and all the children marched to the trains bound for the Treblinka death camp.

Korczak could have escaped at any point, with so many contacts in Warsaw who would have helped their beloved teacher and mentor escape, but he chose to go with his children to the death camps. He said, ‘You do not leave a sick child alone to face the dark and you do not leave children at a time like this.’

I wanted to bring Korczak’s story, the story of his children and teachers and their courage through that terrible time, to a wider audience. I managed to contact the son of two teachers, Misha and Sophia, who had lived in Korczak’s children’s home in the ghetto as helpers and who had been among the 1% to survive the ghetto through some remarkable circumstances.

Ruins of Warsaw

After talking to Misha and Sophia’s son Roman about his parents, I knew I had to tell Korczak’s story from their point of view, through their love story. I went to Sweden to visit Roman and he shared his family photos and notes. Then I visited Warsaw and the sites of the ghetto places where Korczak and Roman’s parents Misha and Sophia had lived. It took several years to complete enough research before I felt I had an accurate understanding of Warsaw, both before and after World War Two. It was a fascinating journey into the past.

I began to find out all I could about Dr Korczak in the British Library, Oxford libraries and various specialist libraries such as The Wiener and The Polish Institute in London. I traced most biographies and first-hand accounts of Korczak, including the diary that Dr Korczak kept through the ghetto years. It was left behind in the orphanage after the children were taken.

Misha had been out of the orphanage on a work detail for his captors when the children’s home was raided and returned to find the children and the staff gone. He gathered up the diary and took it with him when he and Sophia escaped from the deserted ghetto. I was able to reference the memoirs of a couple of boys who had left the orphanage and the ghetto before it was razed to the ground, such as Sammy, who loved music and was once given a mouth organ by Korczak.

He ended up in Auschwitz playing the same mouth organ in an orchestra as relatives were taken to the gas chambers before his eyes. He was able to return to the site of Auschwitz after the war with a group of his Israeli music pupils to play their mouth organs on the same spot as a memorial many years later.

Most of Warsaw and nearly all the Warsaw Jewish ghetto were razed to the ground by the Nazis. The historic centre of Warsaw, which looks so timeless today, is in fact a careful reconstruction from plans and photographs rebuilt just after the war. The ghetto was never rebuilt. I feel that perhaps in a similar way the recreation of the ghetto in the novel of The Good Doctor of Warsaw, done from plans and photos, films, diaries and first hand accounts, was a similar project of reconstruction.

Most of Warsaw and nearly all the Warsaw Jewish ghetto were razed to the ground by the Nazis. The historic centre of Warsaw, which looks so timeless today, is in fact a careful reconstruction from plans and photographs rebuilt just after the war. The ghetto was never rebuilt. I feel that perhaps in a similar way the recreation of the ghetto in the novel of The Good Doctor of Warsaw, done from plans and photos, films, diaries and first hand accounts, was a similar project of reconstruction.

It was a responsibility to recreate such a place, with many corrections by Roman and other sources. I was very pleased when a Holocaust history professor said the book was the most accurate depiction of the ghetto that she had read. The Nazi regime may be long gone, but Dr Korczak’s message of love, hope and fairness remains a shining and beautiful beacon of light even today, with thousands of people across the world still reading his works and listening to his pleas to treat children with love and respect.

Two years ago I was able to attend the International Korczak Association conference in Seattle, US, and the book was give an award for its depiction of Dr Korczak. I had the opportunity to show a montage of old film clips and music to bring to life again the world of pre-war Warsaw, one of the most beautiful cities and beloved of Korczak as his home. I hope The Good Doctor of Warsaw will also be able to bring that world, and the world of the inspirational Dr Korczak, back to its readers.

—

Elisabeth Gifford grew up in a parsonage. She writes for The London Times and the Independent and has a Diploma in Creative Writing from Oxford University and a Masters in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway College. She lives in Kingston upon Thames in England.

Find out more about her on her website http://www.elisabethgifford.com/

Follow her on Twitter @elisabeth04l

THE GOOD DOCTOR OF WARSAW

Set in the ghettos of wartime Warsaw, this is a sweeping, poignant, and heartbreaking novel inspired by the true story of one doctor who was determined to protect two hundred Jewish orphans from extermination.

Set in the ghettos of wartime Warsaw, this is a sweeping, poignant, and heartbreaking novel inspired by the true story of one doctor who was determined to protect two hundred Jewish orphans from extermination.

Deeply in love and about to marry, students Misha and Sophia flee a Warsaw under Nazi occupation for a chance at freedom. Forced to return to the Warsaw ghetto, they help Misha’s mentor, Dr Janusz Korczak, care for the two hundred children in his orphanage. As Korczak struggles to uphold the rights of even the smallest child in the face of unimaginable conditions, he becomes a beacon of hope for the thousands who live behind the walls.

As the noose tightens around the ghetto, Misha and Sophia are torn from one another, forcing them to face their worst fears alone. They can only hope to find each other again one day . . .

Meanwhile, refusing to leave the children unprotected, Korczak must confront a terrible darkness.

“I could scarcely put it down. Vivid and chilling but utterly inspiring.”—The Daily Telegraph

“A story that should be told and retold. Gifford’s version is readable and extremely powerful.”

—The Times

“With powerful themes of loss, hope, and what it means to be human, The Good Doctor of Warsaw is a brave, moving, and important book with a message we need now as much as ever.” —Katherine Clements, author of A House of Ghosts

“Powerful, harrowing, and ultimately uplifting. Elisabeth Gifford has achieved an extraordinary blend of fact and fiction.”—Andrew Taylor, author of The Ashes of London

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips