The Seed of My Memoir in a Glass of Pinot and a Prompt By Gretchen Cherington

At age forty, with two growing children and a new consulting company she’d recently founded, Gretchen Cherington, daughter of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Eberhart, faced a dilemma: Should she protect her parents’ well-crafted family myths while continuing to silence her own voice?

Or was it time to challenge those myths and speak her truth–even the unbearable truth that her generous and kind father had sexually violated her?

for Joni Cole and Penny McConnel

The walls of the room are painted pumpkin orange. The furnishings, I presume, cast-offs from loving friends. On the floor near the door are opened bottles of red wine wedged against a college-style refrigerator sporting a well-used Mr. Coffee on its top. There’s a ball jar with a half-dozen assorted spoons and a chipped china bowl with sugar, bits of it crusted. It’s a cozy, welcoming room for a Friday after work in this barely up-and-coming old railroad town on the left bank of the Connecticut River. I’m here for a Pinot and Prompt.

We sit in a circle of chintz and corduroy chairs. Pinks and reds and brown being their colors as we eye each other with curiosity, maybe a little apprehension. We’re as eclectic as the furniture—fiction writers and memoirists, essayists and comics, poets and flash factories, well published and not; come one, come all.

A young woman with a nose ring and spiked hair sits to my left; a three part-time jobber next to her, tells me he writes on his overnight shift at Dunkin Donuts and he’s well into a novel about local bankers; a rounded-belly guy to my right and a postal worker, next to him; then an engineer, a doctor, a teacher. We each have our reason to be in this room. Joni is one of them.

“Okay,” she says after a quick go-round of introductions. She’s a fashionable, quirky blonde who I’ll learn is witty, wicked smart, and rigorously fair. And passionate, I’ve heard, as an advocate for her writers. At first glimpse, I see a lifetime of laughter built into the tiny creases at the outer edges of her eyes.

She’d been recommended by my friend, Penny, who owns our best indie bookstore. “Joni knows her stuff and is incredibly positive,” Penny had said. That sounded like what I needed to counterbalance the negative feedback I’d been getting from well-intentioned workshop leaders and editors of magazines.

By focusing on everything I’d done wrong, all I’d gotten was an existential angst about writing at all. I was too new to this, too vulnerable about the topic of my original family, too fresh to the concept of memoir. Later I’d want the ‘give it to me straight’ feedback and need it to finish things up and get published, but not back then, when, in my forties, I had the audacity to think I could write a decent paragraph. I believed in only the seed of my idea, that someday—way out there someday—I might publish a book. And that tiny seed was just a figment of my imagination, no more real than the never-ending dream I had to be five foot, seven inches tall.

“There are only two rules,” Joni says. “Put your pen to paper, or your fingers on your keyboards, and keep them moving till I tell you to stop. Just write.”

With no logical beginning, middle, or end? I question. Without thinking it through first? Even if I’d liked what Natalie Goldberg said about “hitching your unconscious to your writing arm,” wasn’t that just theory? Interesting to ponder, maybe, but not a prescription on how to write.

“So,” Joni continues, “here’s your prompt…‘just between you and me’…Okay, go!”

I give it a whirl as keys around the circle click and words gush forward, as if my brain is spewing out sentences my fingers can barely keep up with. A few minutes in, my brain halts. So, too, my fingers. I look up. Joni sees my hands aren’t moving. “Time’s not up,” she reminds the group, and I go at it again.

Five minutes later, Joni calls, “Okay, now time’s up!”

In the space of just minutes, I’ve written about my divorce, continuing anger at my ex that occasionally gets directed at the wrong people, a recent experiment with meditation, an old high school grudge with a girlfriend who stole my ninth grade boyfriend while I was away at boarding school for a year…just between you and me.

All from one glass of Pinot—so far—and a prompt. In those minutes, I toss aside ten years of professional writing as a ceo and another ten as an advisor to executives—the logical, formulaic reports, overheads, and slide decks that will clearly capture an assessment of a workplace—for the freedom of letting my fingers rip. I am hooked on this feeling.

The following month, Joni mixes it up with a grab bag of words and says we’re required to use each one. “Here they are,” she says, “Tickle…Conductor…Toenail…Greasy…Hairpin. Those are your words. Fingers on keyboards. No stopping. Good luck!”

I’m smiling at others in the circle as I waste thirty seconds wondering where she comes up with such concoctions? In the shower, I speculate? Noodling over her morning toast? In her car between traffic lights? But I’m stalling. I put my hands to the keyboard and manage to carve out a story plucked from nowhere about a girl I don’t know named De’Wanda on a train in New York tickling her toenail from her big toe and offering it as ticket to the conductor, who’s heard every excuse in the book.

“Time’s up!” Joni says after we’ve been at it for twenty minutes.

Okay, this is interesting, I think to myself, and then laugh at the ingenuity, tear up at the tragedy, of propellant words a dozen random people offer up from the heart-wrenching to the downright brilliant. Testament to the surprising confluence of Joni’s two rules, this orange painted room, and trust in the process.

Still, while last phrase—trusting the process—is something I’m using with new consulting clients, I’m naturally skeptical of the woo-woo. While this is fun for a Friday evening out, meeting new writing buddies over a glass of wine, what does it have to do with growing my seed of an idea, that one day I might publish a book?

The next month I find out.

“So, here’s tonight’s prompt,” Joni says, “…’she took the stairs like she owned them.’”

And, suddenly, I’m back on the porch that separated my father’s writing study from our family home. It’s 1968. I’m seventeen years old. Anne Sexton is scaling the steps of our porch. I’ve described how Sexton owned those stairs; the pulse in the back of her calves; her Jackie Kennedy green shift and string of pearls; the small entourage of tweed-suited English professors circling her like stars around a new literary sun.

Now, I’m stunned. What I’ve just written is the first vivid scene in closet of memories. And I’ve nailed my experience from back then. The piece will be revised, lengthened, then shortened, and revised again, polished, workshopped and edited. I’ll re-order sentences and question the logic of seeing legs pulse from my vantage point on the porch. I’ll add details from letters I’ll find between Sexton and my father. I’ll read her poems and his from their Pulitzer Prize winning books as she won hers the year after he won his.

But that Friday, back in the late 1990s, at a Friday evening Pinot and Prompt, I had entered the heart of my story, and fallen in love with words I could write, when free. With no then-known beginning, middle, or end to a book, I’d found that quiet voice that belonged to me, one long-kept silent, one wanting to be heard.

—

About the Author

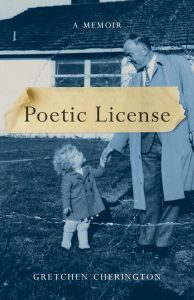

Gretchen Eberhart Cherington is the author of POETIC LICENSE: A Memoir, one woman’s story of speaking truth in a world where, too often, men still call the shots. She grew up in a household that—thanks to her Pulitzer Prize–winning father, the poet Richard Eberhart—was populated by many of the most revered poets and writers of the twentieth century, from Robert Frost to James Dickey. She’s spent her adult life advising top executives in changing their companies and themselves.

Her essays have been published in Crack The Spine, Bloodroot Literary Magazine, and Yankee Magazine, among other journals and newspapers, and her essay “Maine Roustabout” was nominated for a 2012 Pushcart Prize. Cherington is a leader in her community and has served on twenty boards. Passionate about her family and friends, she most enjoys spending time with them at home or in wild places around the world. Learn more at https://www.gretchencherington.com

POETIC LICENSE: A Memoir

At age forty, with two growing children and a new consulting company she’d recently founded, Gretchen Cherington, daughter of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Eberhart, faced a dilemma: Should she protect her parents’ well-crafted family myths while continuing to silence her own voice?

At age forty, with two growing children and a new consulting company she’d recently founded, Gretchen Cherington, daughter of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Eberhart, faced a dilemma: Should she protect her parents’ well-crafted family myths while continuing to silence her own voice?

Or was it time to challenge those myths and speak her truth–even the unbearable truth that her generous and kind father had sexually violated her? In this powerful memoir, aided by her father’s extensive archives at Dartmouth College and interviews with some of her father’s best friends, Cherington candidly and courageously retraces her past to make sense of her father and herself.

From the women’s movement of the ’60s and the back-to-the-land movement of the ’70s to Cherington’s consulting work through three decades with powerful executives to her eventual decision to speak publicly in the formative months of #MeToo, Poetic License is one woman’s story of speaking truth in a world where, too often, men still call the shots..

Category: How To and Tips

Hi Liz, Thanks so much for letting me know and for reading my memoir. You can sign up for my newsletter on my website if interested in news and views, along with updates on my second memoir due out August 2022. As for the Pinot and Prompt, it was a pleasure to have found that teacher, Joni Cole, and we were recently reunited on her podcast “Author Can I Ask You?” (a snappy and fun 15 minutes together). https://feeds.buzzsprout.com/1738426.rss

What a wonderful essay. Looking forward to reading the memoir. Thanks for sharing your voice.