The Weather Here

My own internal and external storms increasingly seem to mirror the weather patterns of climate change. I started noticing this last year, just after turning 60. I closed my law practice, hoping, with my daughter several years out of college, I could turn my attention elsewhere, I could spend time listening to and answering my heart’s true calling. I’d chaffed at being a lawyer, at the time and energy it diverted from my dream of being a writer. But it had been my financial security-blanket.

My own internal and external storms increasingly seem to mirror the weather patterns of climate change. I started noticing this last year, just after turning 60. I closed my law practice, hoping, with my daughter several years out of college, I could turn my attention elsewhere, I could spend time listening to and answering my heart’s true calling. I’d chaffed at being a lawyer, at the time and energy it diverted from my dream of being a writer. But it had been my financial security-blanket.

Sociologists observe that often people who grow up poor never feel financially secure no matter how much money they have. I’d grown up poor, and I didn’t feel safe letting the law go. At least not until Rachel got through college. The year she graduated, I entered the VCFA low-residency MFA program.

Still hedging my bets, I kept my practice open and worked another three years until that landmark birthday when I finally realized it would be worse to leave this life without fully embracing the dream I’d let go decades earlier – the dream of being a writer. Of leaving something that matters. Of living a life as engaged with the heart as the mind.

Three months before closing my practice, Rachel told me she was pregnant. We were in a rental car. I’d taken her to the Oregon coast with me, and we were going to spend a few days whale-watching before driving to Seattle for a writers’ conference. If someone had been watching, they would have seen us cry. Embrace. They might have imagined pure joy. That the thrill of being told I’d be a grandmother five months later brought us to tears. But inside that car, I’d just said, “Are you sure?” And, “If you want to get an abortion, I’ll go with you.” And she’d said, weeping inconsolably, “I would have done that on my own without telling, if I’d wanted to do that.”

I wanted to be supportive, but all I could see was the hardship. The pain. The diminished life. I worried about the wisdom of her decision and timing. Despite a brilliant academic mind, after college she’d withdrawn into a life of enabling the addiction of a man she’d fallen in love with, a handsome, artistic, and deeply troubled alcoholic. She told me he’d gotten sober so she could get pregnant. He promised to stay sober for the baby.

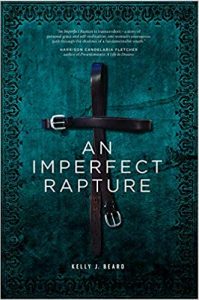

Ten days after closing my practice, I received a call letting me know that Janisse Ray chose my manuscript, An Imperfect Rapture, as the winner of the Zone 3 Press Creative Nonfiction Award. It meant publication with a well-respected university press, a press dedicated to promoting work of literary worth. University and independent presses form the last small buttresses to the increasingly conformist and generic voices of the mega-imprints. At the writers’ conference I’d attended in Seattle (while my daughter slept in the room or by the pool, dreaming, I felt sure, of the loving little family she was creating) I listened to a panel of agents discussing what they were looking for in submitted work. Stories about poor whites in the Trump era were verboten for the large presses.

One agent told a story about “the most breathtakingly beautiful manuscript” he’d ever read. It was a novel about the struggles of a poor white family in North Dakota. He’d never worked harder to get a manuscript accepted by one of the NY houses, but they each gave him some iteration of the same reason for rejecting it: they refused to publish anything about poor white people in this fractious political environment. Knowing this heightened the gratitude and joy I felt those few months later, when Zone 3 Press called to tell me about the award and publication.

The month following that call, Rachel showed up alone for Thanksgiving. Her boyfriend, ostensibly “at work” as a server in a local diner, hadn’t stayed sober, but I didn’t know that until I saw him again, on Christmas eve. He reeled in reeking of alcohol, stumbling and weepy, his face puffy, flushed. When he left, Rachel said, “He’s trying, Mom.” Neither of us had ever loved an addict before. We’d never been this close to the disease. We didn’t know trying was such an unlikely cure.

The alchemical process of turning my manuscript into a book continued. My editor was brilliant and patient. Blurbs from some of my most beloved authors came in, with people like Andre Dubus III calling An Imperfect Rapture “transcendent” “stunning” and “a beautiful book.” I felt that finally I was stepping fully into my life’s purpose.

And yet. I couldn’t shed the worry. The pull of that baby floating in the loamy safety of my daughter’s uterus as though his lima-bean sized body held more gravity than the sun. I couldn’t imagine how my daughter would be able to care for the baby, seeing, as I was beginning to see, how consuming her boyfriend’s addiction was, how it drained her time and energy and money.

When I told a gynecologist friend that she was pregnant he asked where she was going to have the baby. I told him the Atlanta Medical Center was one of the few hospitals accepting Medicaid. He said, “You have to tell her not to. She can’t have her baby there. Those people are horrifying.” I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to have a daughter who would actually do what I told her to do. Stubbornness is one of the unfortunate traits she inherited from me. The best I could do was be close. Hope. Pray. I put our house on the market, over my husband’s pleas against the move, so I could be minutes rather than an hour away from the baby.

Some personal essays of mine were accepted for publication over the next several months. Lovely journals like Creative Nonfiction and the Bacopa Literary Review among them. I was finally starting to feel like a writer. Like I could really do this. At the same time, Rachel’s boyfriend continued to unravel. She tried to hide it from me, but I learned that he was so out of control, his screaming and emotional abuse had stalled her labor for nearly two days.

The Atlanta Medical Center was worse than I’d expected – even after the warning. The nurses were malevolent and incompetent. The baby had meconium poisoning – most likely the consequence of the stalled labor or the nurses terrifying her by telling her the doctor had gone home and was not going to be there to deliver the baby. While he spent his first few days in the NICU, I prayed. Held my breath.

The baby – Wren Clarence – turned one a few weeks ago. He is big and healthy and loud. The joy of seeing his wide-open smile when he catches sight of me eases but doesn’t fully erase the searing images of Rachel convulsing in the hospital bed while the neonatal nurses whisked his tiny blue body away.

A few weekends ago, I appeared on two panels at the Tucson Festival of Books. One was called “Living in the Extreme,” and while the moderator chose it, no doubt, as a thumbnail description of the panelists’ memoirs about our pasts, it seemed prescient, too. While the weather outside lurches between extremes more common for months later or earlier, the weather inside is no calmer. I am learning to live in the whipsaw weather created by the disease of addiction. I am learning that all I can do is to tend my own garden, my dharma, my loved ones: Wren, Rachel, writing. I am learning to live with the weather here.

—

KELLY J. BEARD practiced employment discrimination in the Atlanta area for two decades, during which time she founded the Professional Women’s Information Network (ProWIN) and received multiple awards for her legal and community service. She was recognized as a “Super Lawyer,” a “Star of Atlanta,” and as one of the nation’s “Preeminent Female Lawyers,” and received a certificate of recognition from the Georgia Coalition Against Domestic Violence for her service.

In 2016, she earned her MFA in Creative Writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her work appears in Creative Nonfiction, Santa Ana River Review, Five Points, Bacopa Literary Review and others. An Imperfect Rapture is her first full-length memoir.

https://www.facebook.com/kelly.beard.758

https://www.instagram.com/kellyjbeard/

AN IMPERFECT RAPTURE, Kelly J Beard

An Imperfect Rapture is a coming-of-age story about growing up in the crucible of Christian fundamentalism and white American poverty. Kelly recreates the real-life shadowlands of her youth with the lyricism of a poet and the nuance of an insider.

An Imperfect Rapture is a coming-of-age story about growing up in the crucible of Christian fundamentalism and white American poverty. Kelly recreates the real-life shadowlands of her youth with the lyricism of a poet and the nuance of an insider.

Her unflinching examination of the people and places populating the story offers the reader a rare glimpse into an experience hidden from or ignored by our first-world culture, and its unsparing, fiction-like narrative resonates as both a personal exorcism and a public plea for empathy.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing