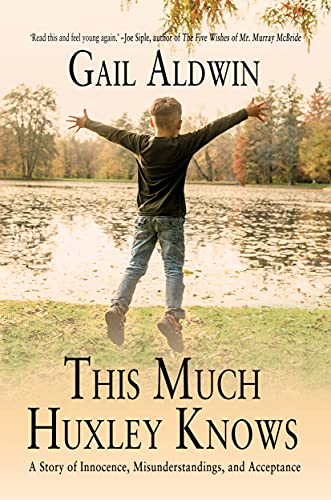

THIS MUCH HUXLEY KNOWS: Excerpt

We are DELIGHTED to partake in Gail Aldwin’s Blog tour with an excerpt of This Much Huxley Knows!

We are DELIGHTED to partake in Gail Aldwin’s Blog tour with an excerpt of This Much Huxley Knows!

About THIS MUCH HUXLEY KNOWS

“Read this and feel young again.” –Joe Siple, Bestselling author of The Five Wishes of Mr. Murray McBride

I’m seven years old and I’ve never had a best mate. Trouble is, no one gets my jokes. And Breaks-it isn’t helping. Ha! You get it, don’t you? Brexit means everyone’s falling out and breaking up.

Huxley is growing up in the suburbs of London at a time of community tensions. To make matters worse, a gang of youths is targeting isolated residents. When Leonard, an elderly newcomer chats with Huxley, his parents are suspicious. But Huxley is lonely and thinks Leonard is too. Can they become friends?

Funny and compassionate, this contemporary novel for adults explores issues of belonging, friendship and what it means to trust.

EXCERPT

The playground at St Michael’s School is a car park tonight. Mum drives into a space and I wait for Dad to open my door. It’s Saturday and this means my teacher won’t be around. Mrs Ward says I’m a nuisance when I’m only trying to have a laugh. I think new-sense is clever, so it doesn’t matter if she calls me that any more.

Families are getting together to make money for our school – there’s never enough to go round. We’re having an auction to sort this out. Grown-ups promise to do something, then it’s sold to the person that gives the most money. My mum and Ben’s mum did a lot of talking about the auction. With her new camera, Paula’s going to take a photo of a family to go in a fancy frame. Mum is doing better by giving away two bottles of her homemade elderflower juice. Yippee! The orange stuff from the supermarket is much nicer. It comes in a bottle the shape of a telescope.

At last, Dad lets me out and I race over to Paula’s car. It’s called a Beetle but I’ve never seen insects that big. Ha-ha-ha. I press my nose against the window to look inside. My breath leaves a cloud.

‘Come away, Huxley,’ says Mum. ‘You’ll set off the alarm.’

I rub my sleeve over the glass to clear away the marks then rush to catch up. She holds my hand and I swing-swing-swing our arms high in the air.

‘Steady on.’ Mum’s a jiggling skeleton. It’s part of our game.

We don’t usually walk through the main door because I’m meant to stand on the line in the playground ready for going into class. I always want to be at the front and I get there by pushing and shoving. If Mrs Ward sees, she sends me to the back and then the bigger children in the next class make fun of me. My teacher never watches when picking-on starts so I have to put up with it. It’s not easy being in Year Two.

We dump our coats on a table in the hall and I spot Ben by the climbing bars that are pushed flat against the wall. As usual, he’s wearing his Malden Town football shirt. I hang around near Mum for a bit and watch what he’s doing. With one foot on the bar nearest the floor, it looks as if Ben’s going to leap to the top. Spider-Man can do it but not Ben. He gives up his chance and comes over to me.

‘Let’s go into our classroom,’ whispers Ben.

‘Why?’

‘To mess around.’

This is not allowed although the idea is exciting. Mrs Ward has rules we’ve heard one hundred times before. I pinch my throat to turn my voice the same as hers. ‘No touching the things on my table!’

‘Or mucking up the books!’ Ben joins in.

We sound like her and I can’t stop smiling.

‘Let’s poke about.’ Ben’s eyes go slanty as he whizzes them round the hall to check it’s safe to sneak off. Mum and Paula are chatting – they won’t see we’re gone. This is our chance!

‘You first,’ I say.

Chairs are on the tables and it’s creepy in the empty classroom. I head for the nature display to have a look at Zac’s squashed toad. He said it was run over by a car and told everyone it was a great find. Mrs Ward didn’t know what was in the bag until the paper split. Surprise made her jump out of her chair and the toad’s leg fell off when it landed on the floor. After that, it wasn’t such a great find but Mrs Ward still made space for it on a special stand. I pick up a felt pen that’s lying about and dig it into the place where the toad’s eye should be.

‘Give me a go,’ says Ben.

He presses in another pen to turn the toad into a Dalek from Dr Who. Me and Ben shout exterminate until we’ve got no breath left. Next minute, our school caretaker comes in. He shoos us back to the hall with the big crowd of parents. I barge through skirts and trousers and forget to say excuse me but Mum doesn’t notice. She gives me a fifty-pence piece to spend at the children’s table. I slip it in my pocket so I won’t lose it.

On the stage, Zac’s mum talks into a microphone that gives a horrible squeak. I stuff a finger in each ear to block out the noise. With the holes plugged up, voices go blah-blah-blah. I shake my head like I’ve gone bonkers. By yanking my hands free, Mum breaks the game. She drops down to bring us eyeball to eyeball. Listening to her serious voice, I stare at the powder on her eyelids that’s smudged and golden. She paints it on with her mouth open same as a fish. I let a snigger slip out.

‘If you can’t behave nicely,’ says Mum, ‘I’ll take you home.’

‘I will be sent-a-ball.’ Smiling stretches my cheeks.

‘That’s hard to believe when you don’t even say the word properly.’

‘But saying sensible is not a joke.’

Mum lets her eyes go up to the ceiling and back.

My dad is getting beer from the serving hatch. That’s where we wait for our school meal but there’s no sausage and mash tonight. I join the queue at the children’s table. When I get to the front, I shoot my coin across and it nearly flies off the other side. A big girl slams her arm down to stop it. She slides a cup of orange towards me. I have a swig but it’s not worth a whole fifty pence.

My dad is getting beer from the serving hatch. That’s where we wait for our school meal but there’s no sausage and mash tonight. I join the queue at the children’s table. When I get to the front, I shoot my coin across and it nearly flies off the other side. A big girl slams her arm down to stop it. She slides a cup of orange towards me. I have a swig but it’s not worth a whole fifty pence.

Ben’s family and my family stand together when the charity auction starts. Everyone goes quiet. I can tell what’s going to happen because I watch daytime TV with Mrs Vartan. She’s our neighbour and looks after me sometimes. To bid at an auction you put your hand up and shout out a number. At school, we have to talk quietly although parents break the rule. The fun is only for grown-ups. It’s boring being left out but I clap at the right time. I try to be the loudest clapper and it makes my hands sting.

‘Thank you.’ Zac’s mum’s voice is loud and strange when she uses the microphone. Her face is bright pink as if she’s been under a heater. ‘Next, we’ve a special lot from our very own Miss Lucy Choi.’

I don’t understand why Zac’s mum says Miss Choi belongs to her. Everyone knows she’s the teaching assistant in my class. I’m allowed to call her Lucy because she’s Mum’s friend. Strange thing is, I forget and call her Lucy at school and Miss Choi at home! Sometimes the wrong name comes out by accident, sometimes I do it on purpose. Zac’s mum reads out loud from the clipboard but I’m interested in watching Dad. He glugs back the last of his beer and then waves his arm in the air.

‘This one’s mine,’ he shouts.

‘Calm down.’ Mum speaks in an extra loud whisper. ‘It’s only a birthday cake.’

Zac’s mum beckons Miss Choi onto the stage. She shakes her head because she doesn’t want to go but Zac’s mum gives her a hand. One big step and Miss Choi’s up there with the others. Her legs are pencils in her black jeans. Ben’s Nanny Phil says everyone from Miss Choi’s country looks the same. When she says stuff like that Paula tells Nanny Phil to shush or she’ll get a reputation. To be funny, I say rip-you-station … although some people never get my jokes.

‘Such enthusiasm for this fantastic offer of a homemade birthday cake in a Barbie or rocket shape,’ says Zac’s mum.

‘Cracker of a lot, Lucy,’ shouts Dad. ‘I’ll give you twenty quid.’

‘What are you up to?’ Mum is staring at Dad.

‘Can’t let you get away with that.’ This time it’s Tony talking. ‘I’ll top you to thirty.’

‘Give it a rest,’ says Paula.

Dad takes a new can of beer from his jacket pocket. Froth spurts as he opens it, so he licks away the mess.

‘Excellent.’ Zac’s mum’s voice bounces around the hall. ‘Any more bids?’

‘Forty pounds,’ shouts Dad.

I can’t understand why Dad wants a cake. My birthday was in September and I had a bouncy castle and a castle cake that came in a huge box. I don’t think much of rocket cakes and Barbies are for girls. But Dad is having fun because he nudges Tony and says, ‘Beat that’.

The dads are mucking around and I can’t be bothered to wait for Tony’s bid. I’m wondering about my next birthday. When I’m eight, I want a pirate party. Dad can wear an eye patch and Mum’s hair is long enough to be Jack Sparrow. My hair goes over my ears to keep them warm.

All of a sudden, Dad’s hand is up in the air again. ‘Great stuff, Lucy,’ he says. ‘Make it sixty.’

Zac’s mum’s eyes are ping-pong balls. ‘How generous.’

Miss Choi folds her arms and shuffles from side to side.

‘Any further bids?’ Zac’s mum is staring at Tony.

‘Why not,’ he says. ‘I’ll go to seventy.’

Paula shakes her head, making her golden hair whip about her shoulders. Then she looks at the floor, like there’s something very interesting on the wooden blocks.

‘Eighty,’ says Dad.

Mum is straight and stiff as a ladder.

‘Marvellous,’ says Zac’s mum. ‘Our highest bid of the evening. Any more takers?’

‘I’m out.’ Tony’s smile turns his cheeks into folds. ‘It’s all yours, Jed.’

BUY THIS MUCH HUXLEY KNOWS HERE

Category: On Writing