Vulnerability in Your Writing and Why it Matters

by Marina DelVecchio

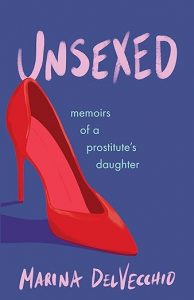

After reading Unsexed: Memoirs of a Prostitute’s Daughter, a friend told me I was brave to write it, followed by, “Don’t you feel vulnerable, writing about your life?”

Many conversations I have had with women in the past few years have brought up similar issues with truth-telling: how much of our truth should we share with others, and what the consequences are for such raw honesty.

One friend told me she never reveals too much to people, even her partner of four years, because doing so gives away her power. People will condemn her, share her secrets, and leave her feeling vulnerable, like walking around with an open, infected wound everyone can see.

In a more recent conversation, a woman told me she does not share everything with her therapist because she doesn’t want to be judged.

There is something about women’s lives that is closeted, perhaps a message we receive from our parents, our communities, our loved ones that are more implicit and full of cover.

Don’t air your dirty laundry.

Don’t trust anyone with your secrets.

Don’t leave yourself open to criticism.

Don’t speak. Don’t complain. Stay small. Take up very little space. And smile.

I have never bought into these warnings or cautionary messages. Not because I am better or more brave than anyone else, but because silence has never served me well. I almost drowned in its suffocating waters, to where suicide seemed like the only way for me to find release. That’s what silence has done for me. How self-denial works in my life, in my personhood.

Revealing ourselves is cut out of our individuality early in childhood, the first time our parents or family members or teachers shut down our veracity, our innocent portrayals of what we have seen and experienced. We are told not to tattle when we see something bad happening to our friends when one child bullies another. We are told not to lie when a trusted adult inappropriately touches us. We are told not to make waves when we are sexually harassed at work or school.

We are taught that the truth has consequences, so we learn to swallow the horrors of experiences until they sink to the bottom of our bellies, growing like cancerous tumors that block out light and health, physical and psychological. The silencing manifests in trauma, grief, guilt and we spend our adult years in therapy, in relationships that return us to the original wounds we buried because someone asked us to hide them, either for our power or theirs.

But this is not power. It’s a weakening of the spine that holds us together. One day, it will crack under the pressure of the truths we keep hidden because that is what happens, naturally and inevitably, with the lies we are taught to tell about ourselves and those who harm us.

What is worse than all of this, though, is that when we don’t share our truths, our experiences with other girls, other women, we send the message that burying who we are and what has happened to us is okay. It’s healthy. It’s what we should all do for self-preservation. Even though our pain eventually comes to the surface to haunt us and our children through generational trauma and harm.

What is worse is knowing that there are other women out there, some even young girls, who are suffering from the same lies, the same pains, and who don’t have the models they need to guide them out of the emotional terrain that is too complex, too dangerous, too heavy for them to unload or release into the light of truth and candid revelations we all deserve.

As someone who was threatened with maternal alienation for telling the truth, I lived for many years in the dark caverns of silence and self-denials. Not only did my mother not reveal herself to me, to guide me, or to bond with me, but she also never prepared me for the real world outside of her austere home: how men would treat me at work, how boys would treat me if I refused to have sex with them, how lovers can turn into monsters, how to stand up for myself in the face of male rage, how to scream and kick when my violin teacher molested me during my paid lessons, how to be a mom to my children without marking them with my trauma. No woman in my life — teachers, doctors, strangers, or mothers of friends — gave me any guidance, either. I had to teach myself all these things, and more, on my own.

Because I had no real life female models, I had to turn to fiction, to literature, to women authors who created female characters who taught me what it means to be a girl, independent, honest, and loving. My mothers and early teachers were Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, the Bronte sisters, Mary Wollstonecraft, Emily Dickinson, Kate Chopin, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. They taught me everything I needed to know about sex and motherhood and love and healing.

This is why I write. And this is why I write the truth, using my life and experiences as a model, laying it all out for the world to read and see and learn — because as I am learning, my experiences quite often mirror the experiences of other women. Our stories are individual and singular, but there are many echoes in the lives of women simply because we are women living in a very sexist and patriarchal society that treats us the same, no matter where we come from.

Whenever I sit down to write, I think of the harms of silence — not only for ourselves but also for the younger generation of women who will one day work, have sex, become moms, and encounter the complexities of sexism that come with being female. I don’t mind being vulnerable if it means my openness will help a young girl or woman who needs to feel seen, heard, and understood. Being vulnerable with ourselves and in our writing is as essential to learning as it is to teaching.

Be vulnerable. Write with vulnerability. Share what you know, so others can see they are not alone. Vulnerability is our bond, and our bravery in writing the truth, no matter how ugly or difficult it is, encourages women in similar circumstances to enact bravery in their lives and writing.

—

UNSEXED

Unsexed examines the role that sex plays in the life of one woman with two mothers who introduce her to polarized frameworks of female sexuality.

Unsexed examines the role that sex plays in the life of one woman with two mothers who introduce her to polarized frameworks of female sexuality.

Born in Greece to a violent prostitute and then adopted by a cold and unloving virgin from New York, Marina inherits a sexual identity steeped in fear and shame—one that, as she grows older and becomes a wife and mother, trickles into her marriage and the parenting of her children. Without the tools needed to understand her complex mothers or to unpack the lessons they taught her, Marina relies on self-erasure to survive relationships that silence and define her—until she finally becomes fed up with those old patterns and begins to stand in her own power.

A memoir that unearths the layered emotional and sexual lives of women and exemplifies the satisfaction that comes when they assert their voices and power, Unsexed speaks to millions of women who have different narratives but face similar struggles in reclaiming their voices, bodies, and sexuality.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips, On Writing