Waiting: A Helpful Guide In Disguise

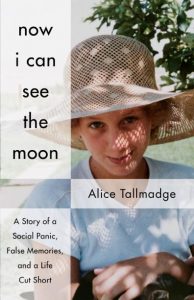

Alice Tallmadge’s memoir Now I Can See the Moon—A Story of a Social Panic, False Memories and a Life Cut Short, focuses on the disturbing social panic over child sexual abuse that roiled communities across the U.S. (and some in Canada and Great Britain) during the 1980s and into the 1990s.

A few years ago, I decided my memoir was done. It had been more than a decade in the making and I thought it was ready. It had a few rough patches, but once an agent or a publisher took it on, I reasoned, we would smooth them out together. (This turned out to be stupendously naive. Today’s much wiser me says: Clean up your rough patches before you submit your queries!) I wrote scores of emails to agents and small publishers, introducing my book, the reasons why these literate business folk should pay attention to it, and to me—me, that is, with no on-line platform, no previous book, no starred credentials, no name recognition and, I realize now, a first-time author hawking her book before she or it was ready.

I got a few kind replies, all no’s. Mostly I heard nothing back. I gave myself daily pep talks, filled in the cells on my Excel spreadsheet, forged ahead to the next agent on my list. I told myself the process was akin to a purification ritual that first-time writers go through before they break through and find the perfect agent match.

It never occurred to me that there were issues with my manuscript that needed more than smoothing, and that they reflected unsolved questions within me.

My memoir, Now I Can See the Moon—A Story of a Social Panic, False Memories and a Life Cut Short, combines a personal narrative with research on the social panic over child sexual abuse that swept the country in the 1980s and into the mid-1990s. The panic included convictions against innocent childcare workers for heinous sex abuse, a burgeoning belief in satanic ritual abuse, a spike in diagnoses of multiple personality disorder, and belief in the absolute validity of “recovered” memories.

I felt at peace with the narrative of my personal story. Even though I spent untold hours researching them, I was less sure I adequately communicated the panic’s complex psychological concepts, particularly the controversial issue of recovered memories. In the 1980s, many practitioners believed that memories of traumatic childhood abuse were “shelved” in the brain until the person was able to process them. The prevailing view of the larger scientific community today is that memory can be manipulated via suggestion, coercion or other influences, and that recovered memories can’t be assumed to be valid. That’s the conclusion I presented in the draft of my book.

But I remained unsettled about the issue. I had interviewed an individual who relayed specific, disturbing memories of childhood ritual abuse. The memories—which, I noted, had been “recalled” during the panic era—haunted the person’s adult life. In the book I frame the memories as false, but I still had questions. How could a false memory have so much power over an individual’s life, for so long? I had heard and read of other incidents of abuse memories surfacing after a long period of time, and not necessarily during therapy. Were those recollections all false?

My eighteen-month-long query process came to a halt after a small publisher I was confident would accept my book, didn’t. The rejection flattened me and I put my publishing ambitions on hold. Several months later, I returned to the manuscript, humbler, clearer, and more compassionate. I cut thirty pages and softened my language. I amended the section on recovered memories. They may be false, I wrote, but that didn’t mean they didn’t engender real pain.

My book was accepted by She Writes Press early in 2017. I was excited, but also a bit uneasy. SWP publisher Brooke Warner writes in her book, Green-light Your Book, that writing a memoir “makes you an expert on the issues you are writing about.” I wasn’t convinced I was.

Last summer, I became fascinated by the Netflix documentary “The Keepers,” about the unsolved murder of a nun in 1960s Baltimore. I was a few episodes in when I realized the documentary was asking the audience to consider the veracity of recovered memories. And the woman doing the remembering was compellingly believable.

Around the same time, I read a New Yorker article about six adults in a small Midwestern town who were convicted of a murder that, DNA evidence later proved, they didn’t commit. At the time of their initial arrests, each had been counseled by a local psychologist who was a proponent of recovered memory. Four of the six became convinced they were guilty. Years after the exoneration, one of them still has memories of being at the scene; another is haunted by sensory “memories” of committing the murder.

A realization hit me: I had been seeing recovered memories in a rigid, either/or framework, whereas, I believe now, they span a spectrum. On one end— and perhaps in a relatively few cases—abuse memories that surface years after an event can be valid; on the other end, false memories can be vivid, specific, and persistent. In a gift of fortunate timing, I discovered a book by a noted memory researcher that explains, in scientific terms, why false memories feel real, and why they persist.

The pieces had lined up. I knew didn’t have to be right in any absolute sense—but I needed to know where I stood. And I finally did. My ambivalence vanished.

All authors need to stand behind our words. If we find ourselves unable to do that, if we sense we carry even a sliver of misgiving, we need to find out why. Sometimes we have to make ourselves wait; sometimes life does it for us. If your momentum is being stalled, try seeing it as an opportunity to look deeper, or reach further. Waiting might be a helpful guide in disguise.

—

Alice Tallmadge has been a reporter, writer, and editor since receiving her master’s degree from the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism in 1987. She was a correspondent for The Oregonian newspaper from 1999 to 2005, and a reporter and assistant editor for the Eugene Weekly in the 1990s. Her essays and stories have appeared in Portland Magazine, Forest Magazine, Oregon Humanities, the Register- Guard, Oregon Quarterly, and The New York Times. Her guidebook for juvenile sex offenders, Tell It Like It Is, was published by Safer Society Press in 1998. She was an adjunct instructor at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication from 2008 to 2014. She is currently a freelance editor.

Find out more about her on her website http://alicetallmadge.com/

About Now I Can See The Moon: A Story of a Social Panic, False Memories, and a Life Cut Short

In the 1980s and 1990s, a mind-boggling social panic over child sex abuse swept through the country, landing childcare workers in prison and leading hundreds of women to begin recalling episodes of satanic ritual abuse and childhood abuse by family members.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a mind-boggling social panic over child sex abuse swept through the country, landing childcare workers in prison and leading hundreds of women to begin recalling episodes of satanic ritual abuse and childhood abuse by family members.

Now I Can See the Moon: A Memoir is a deeply personal account of the devastating impact the panic had on one family. In trying to understand the suicide of her twenty-three-year-old niece, a victim of the panic, the author discovers that what she thought was an isolated tragedy was, in fact, part of a much larger social phenomenon that sucked in individuals from all walks of life, convincing them to believe the unbelievable and embrace the most aberrant claims as truth.

Buy the book HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Alice this hit home for me, not on the topic of repressed or recovered memories, but as far as time being a valuable asset in writing a memoir. Mine has been in the works for 20 years, much of that sitting on a shelf, and recently coming to life again. Had I completed it many years ago, I would not have had the perspective and insights I now have. Congrats on your book!