WAR AND ME: A Memoir by Faleeha Hassan: Excerpt

A nominee for both the Pulitzer and Pushcart Prizes, Faleeha Hassan is known the world over as “the Maya Angelou of Iraq” (Oprah.com), her poems having been translated into twenty-one languages. Through verse, she was able to process the horrors of life during wartime; she was able to give voice to her faith, family and friends, and her hope for the future. Now, in WAR AND ME: A Memoir (Amazon Crossing; August 1, 2022: $24.95), Faleeha Hassan has written a riveting, courageous coming-of-age story told through the lens of war.

A nominee for both the Pulitzer and Pushcart Prizes, Faleeha Hassan is known the world over as “the Maya Angelou of Iraq” (Oprah.com), her poems having been translated into twenty-one languages. Through verse, she was able to process the horrors of life during wartime; she was able to give voice to her faith, family and friends, and her hope for the future. Now, in WAR AND ME: A Memoir (Amazon Crossing; August 1, 2022: $24.95), Faleeha Hassan has written a riveting, courageous coming-of-age story told through the lens of war.

This is also a story about religion, education, politics, sexism, culture, love and loss. Her harrowing story is expertly translated by William Hutchins.

EXCERPT

Chapter Two (pp. 37 – 39)

From WAR AND ME: A Memoir by Faleeha Hassan

Although 1980 was not an auspicious year for a birth, in its third month my sister Hala was born—the final grape in our bunch. That was exactly six months before the disaster. This year and the following ones tattooed all Iraqis with loss and death.

From the start of this year, we had witnessed and heard about unfamiliar events, ones that our ears and eyes found off-putting. We anxiously attributed them to random opinions, but a saying that was often on the tongues of people was: “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” Everyone expected a fierce, blazing conflagration to erupt after smoky rumors circulated with the speed of lightning from one person to the next. These suggested that clashes and serious military attacks had occurred between the Iraqi and Iranian armies. And then there was the September 17 televised appearance of President Saddam Hussein, dressed in a military uniform, during which he declared null and void the Algiers Accord reached on March 6, 1975, ending the struggle between Iraq and Iran. On that fateful day in 1980, the president had that era put to rest. It was the end to the secrecy around events occurring beyond the Iraqi public’s eyes and ears. Suddenly, overnight, all the information that had leaked out on the street from soldiers returning from the borders became a bloody reality that spread across all the following days. Even my subsequent academic success was deprived of its joy, and I received my marks as suspect gifts that brought me no delight.

From the opening day of that school year, which began as usual on September 1, before the events of the catastrophe floated to the surface, where their brutality could be seen by the naked eye, I sensed that something I could not fathom or describe would definitely occur. It would be more brutal than my mother’s illness and more profound than her deep-rooted grief at the loss of my brother Ahmad. I could almost feel the delicacy of its frightening, smooth, effortless advance as it drew closer till it besieged all of us like some giant serpent, depriving us of our vivacity. Teachers—who were at the time an excellent source of news we were not yet allowed to know—whispered to us anxiously: “The Iranian Army launched an attack yesterday on our borders!”

“The Iranian Army bombarded the cities of Khanaqin, Zurbatiyah, Mandali, and al-Muntheriya.”

“They occupied the district of Zain al-Qaws.”

“Our government hanged the prominent religious authority Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr!”

“Sitt Najat’s son died as a martyr at the borders last night!”

“Iran has closed the air space between it and the Gulf states!”

“Iran will inevitably occupy Iraq in a few days!”

I couldn’t share any of this with my family, because any leak that found its way to the ears of government spies—who had sprung up suddenly everywhere, like weeds—no matter how innocent the words were, would wreak havoc on my family. I did not want them to be branded a “fifth column,” since that label would easily and quickly send all of them to the gallows, together with all our cousins, even those four times removed, or to life imprisonment without parole. Each whispered comment dug the trench between me and any peace of mind that much deeper. This gap quickly increased in size till it became a deep ravine, and I could no longer pretend that my day at school had been a regular school day filled only with lessons and learning. No matter how hard I tried to divert my gaze from those whispering mouths, the news issuing from them drew my ears to them. All I could do when I returned home was to climb to my house’s roof and begin to whisper to myself what I had heard, trying to liberate myself from those suppurating secrets. Then I would climb back down to pursue my day’s chores, while remaining hypervigilant.

President Saddam appeared on the official state television channel, Channel One, with a stern expression, wearing his khaki uniform, in which he always appeared from that day till the end of the war, and in a serious, stentorian voice, commanded the Iraqi Army, almost all of whose legions were stationed on Iraq’s borders with Iran: “Combat them, fearless stalwarts!” Everyone took to the streets—not to support the decision to go to war, which had been announced September 22, nor to protest against it. We as a people had no right to reject or accept. We were simply puppets swayed by decisions issuing from the mouth of the government and its president. I, however, attributed the enormous turnout in the streets to the burden that all those secrets had imposed on our breasts, which exploded with a single shout: “With our spirit and blood, we will sacrifice ourselves for you, Saddam!”

At least now, everyone shared the war’s news, no matter how brutal it was. Such information was no longer considered the monopoly of one group, and everyone, both men and women, became political analysts. Their commentaries, which were not informed by military expertise but by their imaginations and which totally contradicted views expressed on television, quickly became a way for people to escape the terrifying question that troubled all of us and limited our ability to make predictions. It was what we asked everyone around us once, and ourselves, repeatedly: “What do you suppose will become of us?”

—

WAR AND ME: A MEMOIR

An intimate memoir about coming of age in a tight-knit working-class family during Iraq’s seemingly endless series of wars.

Faleeha Hassan became intimately acquainted with loss and fear while growing up in Najaf, Iraq. Now, in a deeply personal account of her life, she remembers those she has loved and lost.

As a young woman, Faleeha hated seeing her father and brother go off to fight, and when she needed to reach them, she broke all the rules by traveling alone to the war’s front lines―just one of many shocking and moving examples of her resilient spirit. Later, after building a life in the US, she realizes that she will coexist with war for most of the years of her life and chooses to focus on education for herself and her children. In a world on fire, she finds courage, compassion, and a voice.

A testament to endurance and a window into unique aspects of life in the Middle East, Faleeha’s memoir offers an intimate perspective on something wars can’t touch―the loving bonds of family.

BUY HERE

—

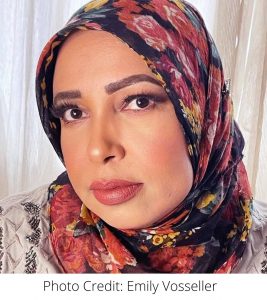

Faleeha Hassan is a poet, playwright, writer, teacher, and editor who earned her master’s degree in Arabic literature and has published twenty-five books. A nominee for both the Pulitzer and Pushcart Prizes, she is the first woman to write poetry for children in Iraq. Her poems have been translated into twenty-one languages, and she has received numerous awards throughout the Middle East. Hassan is a member of the Iraq Literary Women’s Association, the Sinonu Association in Denmark, the Society of Poets Beyond Limits, and Poets of the World Community. Born in Iraq, she now resides in the United States.

Faleeha Hassan is a poet, playwright, writer, teacher, and editor who earned her master’s degree in Arabic literature and has published twenty-five books. A nominee for both the Pulitzer and Pushcart Prizes, she is the first woman to write poetry for children in Iraq. Her poems have been translated into twenty-one languages, and she has received numerous awards throughout the Middle East. Hassan is a member of the Iraq Literary Women’s Association, the Sinonu Association in Denmark, the Society of Poets Beyond Limits, and Poets of the World Community. Born in Iraq, she now resides in the United States.

Category: On Writing