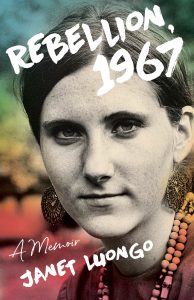

What Inspired Me to Write Rebellion, 1967: A Memoir by Janet Luongo

What Inspired Me to Write Rebellion, 1967: A Memoir by Janet Luongo

What Inspired Me to Write Rebellion, 1967: A Memoir by Janet Luongo

To tell the truth, I feel I was less inspired and more driven to write my memoir. I needed to come to terms with dysfunction in my family and turbulence in society the year I came of age. My story begins in spring, 1966, when I about to enter college in New York at age seventeen, and runs through my eighteenth birthday into The Summer of Love, 1967.

Earlier, during my childhood in Queens Village, New York City, my Irish father turned me on to great literature, which certainly inspired me to write. He encouraged me to keep a “log,” which ship captains used to record details of a journey. I began my habit of logging my private journey, pouring my heart out, filling diaries and journals.

A role model was Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, who created an adventurous character, Jo March, remarkably like herself. Jo broke norms for females in the mid-nineteenth century by publishing a book, as did Alcott (using a pen name then, because, it was thought, who would read a book by a woman?) Alcott’s New England family mingled with Transcendentalists who socialized with Unitarians. I embrace the mission of Unitarian Universalism to “seek the truth.”

I was forced to face truth in 1966, as confusion abounded in my family. Break-ups, moves between states, and failed reconciliations compelled me to track my emotions. Journaling kept me real, grounded, and helped me find my way forward. I also immersed myself in books. Henry David Thoreau, a Transcendentalist, influenced me when he wrote about going off to live in the woods: I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life …and, if it proved to be mean,…publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it.

I didn’t go off into the woods but into the ghettos in New York City. I wrote about a Black painter who mentored me, a Black activist in Jamaica whom I helped develop Great Society programs, and a Black neurosurgeon who offered free clinics for poor people. I faced “essential facts” and I gave “a true account” in my journals of the brutal impact of centuries of racism. I wrote about the comfort and purpose I found in the Black community.

Personal experiences were my main source of inspiration. At seventeen, I was hungry to know life firsthand. My parents set me up in my own apartment in near Jamaica. After one term, I left college to study art and work in a bookstore in Manhattan, where I felt immersed in all the Sixties movements for liberation: for Black people, but also for women, students, and conscientious objectors to war. Everything I absorbed through my mind and senses got captured in my journals: exhilarating dancing in the Dom on St. Marks Place; hearing and marching with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., grooving to jazz in nightclubs and African drumming at Olatunji’s center in Harlem where posters read, “Black is Beautiful.” I thought the world sublime.

In the East Village, on Memorial Day, a peaceful mix of Ukrainians, Black and White students, hippies, and Puerto Ricans playing drums were enjoying a picnic in the park. The sublime switched to meanness in a second. Police in riot gear busted in and made arrests. I joined a protest outside the courthouse against the excessive use of force, which caused my father, a policeman, to explode. In fear and fury, I rebelled and ran away with the jazz musician. Curious, and resourceful, we did experience some highs, soon followed by instability, conflict, poverty, heartbreak and danger, which I faithfully recorded.

The stress caught up to me. While recovering a few years later, in 1970, I came upon my journals from my rebellious year, 1967. Reading about terrible circumstances made me think, This is really great material. I smiled. I looked honestly at who I was and what I’d done, and crafted multiple journal entries into one story.

I got busy with my life: finishing my degree, teaching, and marrying a man who appreciated how I’d healed myself. I kept the manuscript hidden until 1978 when we moved to Switzerland. Unpacking and re-reading it, I felt moved by the struggles of my adolescent self. I almost heard her saying, “It’s a damn good story. Finish it. Telling the truth will help others get through hard times.” I typed out the second draft. When my son was born, it went back under the bed.

In 2011 I found myself missing my son who’d grown up and moved away, and grieving the loss of my mother. I hadn’t told them details of what I’d been through. Once again, I felt the girl of my youth calling me, “You’re free now. NOW is the time to tell the truth.” I joined a writing group, read the unabashedly honest memoirs of Mary Karr, finished a new draft in one year, made countless revisions, and after ten years my story with all the gritty details got a publication date in 2021.

What inspired me to keep resurrecting the manuscript? Over fifty years ago, Dr. King, echoing Jesus in the Gospel of John, stated, “The truth will set you free.” In our current climate, the call for freedom and justice rings from sea to sea, and telling personal truth is more important than ever. Consciousness is evolving. On the individual and national level, it’s time to face the full truth of who we are and what we did, and make the needed changes so we can truly liberate ourselves.

—

Janet Luongo writes stories, creates art, and gives speeches and workshops. Raised Unitarian Universalist in New York City, she holds an MSEd from Queens College at CUNY and taught art from kindergarten to college. While teaching at the International School of Geneva over several years, she exhibited paintings in Geneva and Paris. In Connecticut, she taught communication at Sacred Heart University. As an art education curator in Bridgeport museums, her innovative programs garnered grants, awards and media attention for connecting urban and suburban children and developing leadership in underserved teens. Her book, 365 Daily Affirmation for Creativity, with a foreword by Jack Canfield and published in five countries, led to presentations in the US and as far as Xian, China. To make diverse feminist artists visible, she founded a non-profit, which mounted forty exhibits. She coproduced the movie Women Make Art, which was screened at the UNIFEM film festival. Currently, photography is her art. She resides with her husband, Jim, in Norwalk, Connecticut, and they enjoy hiking with their son and family in Colorado.

ABOUT REBELLION, 1967

Janet Duffy, a spunky, seventeen-year-old Irish girl, is eager to start college―but instability between her alcoholic father and self-absorbed mother jeopardize her dream, so she sets up her own apartment with her younger sister in Jamaica, Queens, and treks to City College in Manhattan, New York. The routine is deadening, but she finds purpose in the black community, working for a mural painter and volunteering for a civil rights activist.

Janet Duffy, a spunky, seventeen-year-old Irish girl, is eager to start college―but instability between her alcoholic father and self-absorbed mother jeopardize her dream, so she sets up her own apartment with her younger sister in Jamaica, Queens, and treks to City College in Manhattan, New York. The routine is deadening, but she finds purpose in the black community, working for a mural painter and volunteering for a civil rights activist.

After turning eighteen, Janet marches with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and falls for a young black saxophone player, Carmen. Her father, a policeman, explodes over their relationship, so Janet rebels―runs away with the jazz musician, and then winds up in the East Village in the Summer of Love. In the ensuing months she deals with heartbreak, sexual harassment, poverty, and danger―but eventually, she asks for the help she needs in order to pick up the pieces of her life and return to her dream.

“Now is the best time for this memoir to come out. Janet has an important message to deliver.”–Sonja Ahuja, Capacity Building and Training Partner, Co-Creating Effective and Inclusive Organizations (CEIO)

Buy here

Category: On Writing