What’s the Point of Point of View?

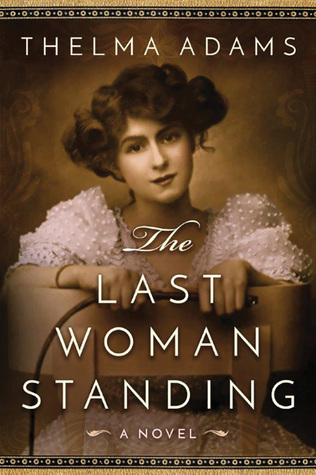

The changing use of point of view has had an impact on everything I’ve written. The most visible example is in The Last Woman Standing, a historical novel about Wyatt Earp’s true love, Josephine Marcus, which I wrote and rewrote over a period of years and stages of child development.

The changing use of point of view has had an impact on everything I’ve written. The most visible example is in The Last Woman Standing, a historical novel about Wyatt Earp’s true love, Josephine Marcus, which I wrote and rewrote over a period of years and stages of child development.

In the final manuscript the book, set in the 1880s in Arizona and California, is told in first person. In some ways this was a strong and bold choice. The book reads like a revealing memoir (I’ve written a lot of nonfiction) of a young woman falling in love for the first time.

While the book integrates historical details, and larger conflicts on the stage of The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral memorialized in such movies as High Noon, by choosing to see the world solely through the eyes of an unseasoned and passionate woman, the book veered into historical romance territory. That was largely a result of the first-person point of view – this character has hot pants and men on her mind and that infuses the storytelling.

Because of that first-person point-of-view, the narrative is never more politically sophisticated than Josephine is, or more detailed than current events she would read in the newspaper. My wonderful editor at Lake Union Publishers, Danielle Marshall, has complimented me on my ability to open up fictional characters, dive in and channel their emotions.

In my mind, first-person narration cracked open this story for me. It was fun to flounce around as the most beautiful woman in Tombstone, a woman that men fought over all the way to Wyatt Earp’s famed gunfight. And, yet, it also limited my field of vision, and lacked the psychic benefits gained by having an omniscient narrator sailing along on the more flexible third person.

The book’s voice and the first-person point-of-view became one, which I’m convinced worked for this particular story, although it was not a choice that appealed to all readers. But, then again, what does? Check my Amazon reviews, where five stars are the majority but they coexist with the one-stars who often resisted the sexual intimacy that I thought natural for this perspective.

The notion of voice has always been essential to my day job as a film critic. It’s a cliché that everybody is a critic, and I’ve spent enough family gatherings proving that point, but to be a professional you have to have a consistent point-of-view.

When, in 1993 and fresh off the MFA Program at Columbia’s School of the Arts, with a comic novel entitled Girl Empire, I applied to the New York Post, the great Editor Steve Cuozzo asked me not for the usual three-to-five clips but for forty. In those days before the internet, that meant a lot of Xeroxing. But it was worth it. What Steve wanted to know was whether I had a consistent voice, a consistent point-of-view that would carry over writing at a daily newspaper. And, in reading all those clips, from my time writing for my college papers and then local Manhattan weeklies like The Westsider, the proof of my potential was the sound of my voice emanating from the written words.

When I was still pretty green at writing fiction, I sought advice without really vetting the source. In one case, a friend’s writer girlfriend told me that having a voice in writing was like looking in a mirror, putting on a hat, and assuming that enhanced persona as a writer. Maybe that was good advice for some but it seemed artificial to me at the time. I discovered that being able to see myself in the mirror as near to whom I really was, to write not for others but as close to my own truth as I could cobble together with words and commas and paragraphs determined my voice – sometimes funny, sometimes shrill or shrewd, always close to my heart.

Now working on my third contracted novel (of four and a half written novels and a memoir), I’ve discovered that what works for one book, or for a critic at the New York Post, Us Weekly or The Observer, doesn’t always carry over to the next adventure.

While I was awaiting the publication of The Last Woman Standing, I began work on my next book, under the working title Kosher Nostra, which will undoubtedly be changed (The Husband Thief? Not so Pretty Now? When is Enough, Enough?). I wrote the first 45 pages of my current historical novel about the lives of the mothers and sisters of a rising gangster involved in Brooklyn’s Murder Inc., as if the story of The Godfather was told by Kay and Connie. Upon reading those pages, Ms. Marshall had one suggestion, which I could take or leave: consider shifting from first to third person. Despite the usual writer pen-dragging, over the next 24 hours I realized that her suggestion felt right, as if I had already been moving in that direction but didn’t have the bravery to change course.

While it might have been more natural to revise from the beginning, I took a double leap – not only expanding the point-of-view but also, for the first time in my writing history, writing the end of the book first. I wanted to use that POV with fresh insight, not merely schlep back to the beginning and revise.

So a by-product of this decision to change POV was nailing down the end so that I could weed out unnecessary earlier plot-lines before I wrote them. As for narrative voice, I needed to dive deeply into character studies of an older sister and mother that I had only seen from the little sister’s sympathetic but biased viewpoint. It was this last change that cracked the current book open for me. Now I wasn’t just the bruised little sister looking out at the world from 1905 to 1935, but I had access to women with very different experiences and the ability, in the case of the mother, to recall the old country (Drohobych, Ukraine) to understand the roots of her mindset – and have compassion for emotions that may put her in direct conflict with her American-born daughter.

I am still looking for third-person hacks – how to reveal the feelings and reactions of various characters through their body language and dialog when I don’t have access to their thoughts. I still cringe when I view my beloved little sister through her mother’s critical gaze. But, by honoring the feelings of characters of whom I wasn’t originally sympathetic, I have vastly expanded my empathy both on and off the page.

Perspective, point-of-view and voice are a journey – and I find that one of my greatest joys in writing my current novel is meeting the challenges of third-person narration and enriching my storytelling in unexpected ways. I always appreciate that feeling of hydroplaning in a novel, when the characters reveal things to the writer that weren’t in the outline (if you use outlines).

In The Last Woman Standing, I found that I would know when the characters would have sex, but once I started writing their intimacy surprised me. Recently, as I wrote Page 101, I discovered the anger of one character stemmed from a miscarriage she’d had the day before. Suddenly, her displaced rage made sense. She talked to me, bossed me around, really – and since I was working in third-person, I listened. And because I’d suffered a miscarriage myself between my two children, I could honor her pain even if her reaction could not have been more different from my own.

As a critic, I have a single voice. As a novelist, I have access to a chorus.

—

Bestselling novelist Thelma Adams (The Last Woman Standing, O Magazine Pick Playdate) has interviewed Mark Ruffalo, Julianne Moore and Diane Keaton for the New York Observer and contributes regularly to Variety.She co-produced the hit TV showFeud: Bette and Joan. She twice chaired the New York Film Critics Circle, reported on film festivals from Berlin to Marrakech, reviewed movies for The New York Post and Us Weekly, and covered the Awards circuit for Yahoo Movies.

Bestselling novelist Thelma Adams (The Last Woman Standing, O Magazine Pick Playdate) has interviewed Mark Ruffalo, Julianne Moore and Diane Keaton for the New York Observer and contributes regularly to Variety.She co-produced the hit TV showFeud: Bette and Joan. She twice chaired the New York Film Critics Circle, reported on film festivals from Berlin to Marrakech, reviewed movies for The New York Post and Us Weekly, and covered the Awards circuit for Yahoo Movies.

Follow her on Twitter @thelmadams

Find out more about her on her website http://www.thelmadams.com/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Comments (2)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post