WHY WRITE A MEMOIR?

WHY WRITE A MEMOIR? By Marilyn Webb Neagley

Some say that writing a memoir is an act of redemption. That has been true for me. I wanted to say “thank you” and “I’m sorry” to those with whom I’ve been closest. I also wanted to share the richness of a life that was pleasantly, and not so pleasantly, imperfect. Attic of Dreams might offer solace, or “a way out,” to others who are living imperfect lives.

Some say that writing a memoir is an act of redemption. That has been true for me. I wanted to say “thank you” and “I’m sorry” to those with whom I’ve been closest. I also wanted to share the richness of a life that was pleasantly, and not so pleasantly, imperfect. Attic of Dreams might offer solace, or “a way out,” to others who are living imperfect lives.

It’s also true that memoir, a collection of memories, helps to heal, to find meaning in one’s life story, for the author, and for the reader. I’ve noticed that sharing my memories most often has a mirroring effect by evoking the memories of others.

My memoir began forty plus years ago, when I was closer in time to my childhood memories. Having limited hours as a working mother, I jotted down memories from my childhood during periodic retreats. A stack of index cards held my recollections before the age of computers.

I was preparing to work with “bits and pieces,” like the slow process of assembling a quilt with fragments of fabric. My bits and pieces appeared as an array of colorful light and somber darkness. They included patterns of human figures, and other intricate elements of nature.

Years later, I was ready to begin. Writing a memoir felt, at first, like entering treacherous territory. The question of ego was the first to arise. Then there was the question of possible harm done to others. These concerns, and more, were answered in the Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. She added that it was essential to have a good memory, and to be honest. She also provided an extensive list of memoirs written in diverse styles. I immediately and extensively began to read others’ memoirs.

The story that I wanted to write was similar to The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls. I wanted my memoir to be less sorrowful, but equally forgiving. Little Heathens by Mildred Armstrong Kalish was written late in her life, as my memoir would be. Her timeline, like mine, contrasted the speed of change during this technological era with an earlier, simpler life. The beautiful and tender language of Elizabeth Alexander’s memoir, The Light of the World, taught me to favor poetic narratives, to be more lyrical in my approach.

Preceding my first draft, I utilized journals, correspondence, photo albums and news clippings to create a timeline. Researching family history with relatives and town clerks added great enjoyment to my process.

I began to write every morning for two to three hours, and read memoirs of others in the afternoons or evenings. For the first four or so years, I simply wrote my whole story. Along the way, I shared relevant excerpts with many of my characters. This helped to hone accuracy and to prepare my characters for inclusion in the manuscript.

As my first draft was completed, I received an email from a man who claimed to be my half-brother by my father. After three genetic tests, he was proven to be correct. This discovery altered my story. I was no longer an only child. Certain painful family events were finally explained. I briefly spiraled into an emotional hole.

Emotions can run high when writing a memoir. I was concerned about how my story treated those who were closest to me. Where were the boundaries between public, private, and personal? I wanted to respect the readers’ rights to an honest account while protecting the most personal rights of my characters, and myself. At the same time, I wished to share enough detail to possibly help others who had lived with similar circumstances.

One day, a young woman editor from my neighborhood came by. She asked whether I would be writing about one episode, or the whole story. I stated that my story couldn’t be told without the beginning, middle, and end. She then suggested that I read Safekeeping, a contemporary memoir with short chapters, written by Abigail Thomas. The young woman from my neighborhood became my developmental editor.

At that point, I began to rewrite my entire manuscript with short chapters, to make the “whole” story more palatable for the reader. And as I thought about it, memories are seen in the mind’s eye as though looking through a telescope. We see the moment as a vignette, not as an entire episode. And, given this age of new technologies, the attention span of some readers may be shorter.

I also changed the tense from past to present. Writing in first person, present tense, provided greater freedom related to overlapping timelines. This change also helped me retrieve obscure thoughts and feelings with greater clarity and depth. Although, I was then challenged to write with the changing voices of a child, an adolescent, and an adult.

Upon the completion of writing and developmental editing, I began to work with the woman owner of Rootstock Publishing.

With few exceptions, it was women who helped me piece my past together and bring Attic of Dreams to fruition. I was inspired by other women writers, supported by two women editors, and led by my publisher. The town clerks of four towns helped me trace the lives and the settlement patterns of my ancestors.

In approximately 1932, my paternal grandmother left behind a cache of letters and photographs that I later came upon. Those, along with my late mother’s carefully organized records and photo albums, provided details that were essential to writing my story.

One aunt, a cousin, and three childhood friends shared their recollections with me. And, from the beginning, one dear friend gently and persistently said, “You can do this. I know you can.”

—

Marilyn Webb Neagley is the author of two previous books and the co-editor of another. Her book, Walking through the Seasons, received an IPPY gold medal for best northeastern non-fiction. She has been a Vermont Public Radio commentator and has written essays for her local newspaper. She and her husband reside in Shelburne, Vermont. Visit her website, www.marilynwneagley.com.

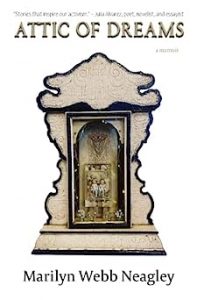

ATTIC OF DREAMS

A lyrical memoir that begins in a quiet Vermont village with memories of Marilyn’s parents, who own a popular restaurant and lively night spot that sits next to their home. While her mother disappears into addiction, Marilyn grapples with feelings of abandonment, though she recalls being uplifted by the village, by her dreams, and by the kindness of others.

A lyrical memoir that begins in a quiet Vermont village with memories of Marilyn’s parents, who own a popular restaurant and lively night spot that sits next to their home. While her mother disappears into addiction, Marilyn grapples with feelings of abandonment, though she recalls being uplifted by the village, by her dreams, and by the kindness of others.

In young adulthood, she lands on a beautiful estate known as Shelburne Farms, where she helps to launch valuable movements for the region: local food and farmers’ markets, outdoor childhood education, and the stewardship of natural resources. But her work is not without cost to her personal life. She discovers that her interest in protecting the outer world begins to heal her inner self. The two are deeply intertwined.

Attic of Dreams examines family dysfunction while humor counters tragedy, and forgiveness counters blame. Trust and love emerge as the journey home to wholeness continues.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing