Write What You Know: Is she Based on You?

Write what you know…

‘Is the woman based on you?’ my friend asks. ‘I mean, have you really behaved like that?’

‘Is the woman based on you?’ my friend asks. ‘I mean, have you really behaved like that?’

Her eyes are widening, her brow furrowing; I can imagine the kind of thoughts crowding through her head. She has just read my novel and is wondering whether the protagonist I’ve created, may be ever so slightly autobiographical. This friend thought she knew me, but she’s now wondering whether the middle-aged woman in my story who has had affairs/ neglected her children/ lied to her friends/ embezzled her employer/ thrown her aged parents into a care home and stolen their money (delete as appropriate) may be based on a real-life person. Me. The author who created her.

‘No!’ I say, laughing too loudly, to show how ridiculous that is. ‘None of my characters are based on me. Not in the slightest. Or on anyone I know. Why would they be?’

Because of course the whole idea is ridiculous. The characters scattered throughout my books and stories are often caught up in traumatic situations. Their lives are unhappy and stressful (at least at the outset) and they do crazy things. One of my previous (unpublished) books was about a woman who falls in love with a stranger: she stalks him, becomes obsessed with his girlfriend and ruins her own marriage into the bargain. NOT me.

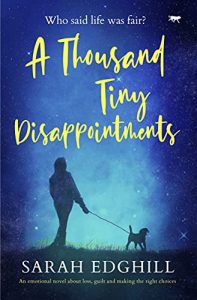

In my debut novel, A Thousand Tiny Disappointments, the main character, Martha, discovers her dead mother has left her home to the dog walker. Overwhelmed by other issues in her personal life and struggling with grief and resentment, Martha makes some bad decisions – the biggest of which is to destroy the evidence… Again, NOT me.

So, of course these women aren’t autobiographical. Hah! Perish the thought.

Except… maybe that’s not quite true? All authors write about what they know – we’re advised to do precisely that, because it’s what we’ll do best. If you write from personal experience, you can do it so much more intensely, because you know how it feels to say those words, to act in that way, to have those sorts of things happen to you.

I admit I’ve frequently stolen and reproduced characteristics: a neighbour whose hair is bright orange and piled into a teetering beehive, made it into short story (even if she never knew it) and I regularly listen in on (and jot down) snippets of conversation overheard at bus stops or in the supermarket.

But there’s a difference between drawing on your own life experiences and things you see and hear, and recreating a version of yourself in a novel. And that’s maybe why I deny any autobiographical similarity so strongly. Some of the women I create and write about are not particularly nice people, but most are good-hearted, kind and hard-working; they are just under so much pressure that they behave in ways they later regret. As an author, my aim is to put my characters in these awkward situations and then throw so much at them that they’re pushed to their limits and have to cope with the fallout.

Ultimately, I will create happy endings for them – or at least ensure the challenges they face will help them come out the other side stronger, more resilient and able to make some good decisions about their lives and their futures. But the journey won’t be easy and the way they behave along the way won’t always be admirable. If that wasn’t the case, it would make for a pretty dull book.

So back to the premise. Are these flawed – often weak, sometimes vulnerable – women based on me? While the answer is still generally no, if I’m honest, I think there must always be a little bit of me in the characters I create. It may only be the occasional turn of phrase – after all, when I hear them talking in my head, they will probably use language and intonation that I use myself. Or it may be the way they handle a situation, or how they react to their husband, friend, mother or daughter in a particular scene I’ve created.

I may not have had those exact thoughts, but I’ve probably gone through something similar. My stomach has flipped at the sight of a good-looking man, I’ve gone into shock when someone I love has died, I’ve felt the hurt of a friend’s betrayal, I’ve been brought up short by a relative’s cutting remark. All of those life experiences – and so many more – have worked their way into my writing, possibly at times subconsciously. The end product is a novel that consists of imagined characters, but every single one of them is peppered with tiny, often insignificant bits of me.

So, when that friend of mine reads about Martha, in A Thousand Tiny Disappointments, and asks, ‘Is she based on you?’ my immediate reaction will still be to laugh and shake my head. But my honest response should be, ‘No, she’s not based on me, but there’s a lot of me in her. I understand her, I sympathise with her and I like her – even though she makes some dubious moral choices.’ And while my friend may not understand that, I think many other writers will know just what I mean.

—

Sarah Edghill worked as a journalist for many years, before turning to fiction. She attended the Faber Academy Novel Writing course in London and won the Katie Fforde Contemporary Fiction Award for an early novel Wrecking Ball. She has been long- and short-listed in several short story and novel competitions and won 1st prize in the UK’s National Association of Writers’ Groups Short Story Competition. She lives in Gloucestershire with her husband, three children and far too many animals and her debut novel, A Thousand Tiny Disappointments will be published by Bloodhound Books on 21st September.

T @Edghillsarah

I @sarah.edghill

A THOUSAND TINY DISAPPOINTMENTS

“A thoroughly gripping story about grief [and] unexpected friendship . . . Sarah Edghill knows how to pinpoint what goes on in families.” —Rachel Joyce, author of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry

“A thoroughly gripping story about grief [and] unexpected friendship . . . Sarah Edghill knows how to pinpoint what goes on in families.” —Rachel Joyce, author of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry

Martha is being pulled in too many directions, trying to be a good mother, a loving wife, and a dutiful daughter. Despite it all, she’s coping. But then her elderly mother is rushed to the hospital and dies unexpectedly, and the cracks in the life Martha is struggling to hold together are about to be exposed.

When she discovers her mother has left her house to a stranger, she’s overwhelmed by grief and hurt. Getting no support from her disinterested husband or arrogant brother, Martha goes on to make some bad decisions.

If she were a good daughter, she would abide by her mother’s final wishes. If she were a good daughter, she wouldn’t destroy the evidence . . .

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing