Writing Syria

Those of us who write are always more than just writers. We are parents, children, workers, volunteers, gardeners, tree huggers, high-flyers, low-flyers, all types of flyers. I am a writer who (sometimes) combines writing with social activism.

Those of us who write are always more than just writers. We are parents, children, workers, volunteers, gardeners, tree huggers, high-flyers, low-flyers, all types of flyers. I am a writer who (sometimes) combines writing with social activism.

In 2013 I became a volunteer activist for Syria Solidarity UK. We work with refugee and other activist groups, and we campaign against the bombing of civilians by the Assad regime and its Russian and Iranian allies. As readers will no doubt be aware, the moderate opposition to the Assad regime has suffered in the most appalling manner, and now, in parts of Syria, the Islamic State and other militant factions have taken control further complicating an already complicated and tragic war.

I make no secret of, nor do I apologise for my partisan approach to this conflict. However, as a fiction writer it is best not to preach to readers, and is important for writers to consider the moral grey areas. As writers, we must attempt to think our way into the motives of others, even those we disagree with, or perhaps abhor. There is also the difficult question for any writer who is an outsider (I am not Syrian and I have no direct experience of the horrors of war) which concerns the moral legality of writing about the plight of others – and/or of co-opting others’ stories. This is an endlessly contestable area, as it is for journalists and war photographers. When does writing about, or photographing a dead child on the street, turn into voyeurism rather than an important piece of journalism or writing? Writers must always question their intentions but we all have a common humanity, and writers have a duty to write about the world as they see it.

When I first attended writing classes there was some emphasis on ‘writing what you know’ as if writers were not able to see inside the head of person from history or different culture. Yet in one sense, in writing these pieces, I am writing what I know. My activism has enabled me to meet and talk to Syrians, both on social media and in my day to day life. I have read extensively on the history of the country and the conditions that led up to uprising and subsequent war, and though I am lucky never to have endured war myself my mother brought me up on first-hand accounts of her life as a teenager during the Manchester blitz. She lost her older brother and father in the Second World War and that tragedy has walked through my life, and our family’s life, as a dark shadow.

I did not sit down and plan this collection. The project just grew over time. I began to jot down small pieces – my emotional responses to the war – and later, refugee friends told me their stories, while other pieces came to me after reading newspaper articles and blogs, or as I was out on the streets demonstrating. All the pieces are short and some are only a couple of lines long, but this short form seems to fit the subject matter. I have intentionally used different viewpoints and narrators – from refugees to refugee workers, from combatants to victims, as well as my experiences and thoughts, but I did make a decision not to write from the regime side, except for the one story, ‘The Reluctant Soldier.’

I did not sit down and plan this collection. The project just grew over time. I began to jot down small pieces – my emotional responses to the war – and later, refugee friends told me their stories, while other pieces came to me after reading newspaper articles and blogs, or as I was out on the streets demonstrating. All the pieces are short and some are only a couple of lines long, but this short form seems to fit the subject matter. I have intentionally used different viewpoints and narrators – from refugees to refugee workers, from combatants to victims, as well as my experiences and thoughts, but I did make a decision not to write from the regime side, except for the one story, ‘The Reluctant Soldier.’

Usually it is men who wage war and men who write on war. Women fiction writers and journalists are now tackling the subject of war and conflict in larger numbers though few women write about the experience of combat. I think it is still harder for women writers to be recognised when writing ‘big’ subjects. An expectation continues to persist in some quarters that women will tackle the domestic stuff, both in their real lives and their writing.

On a final note, I would like to stress the importance of us here in the West listening to the voices of Syrians and Syrian women. Syrian women are writing about the war – through blogs, poems, short stories, and in other ways. Some write in English, or have been translated into English. Others remain untranslated and many others will not be able to write until they have reached a place of safety and distance. I would point readers to the work of Maram al-Masri, Mohja Kahf, Najat Abdul and Dima Yousf, and Samar Yazbek who has written two factual accounts of the Revolution. I am sure there are others I have not heard of, and yet others whose voices will rise from the ashes.

—

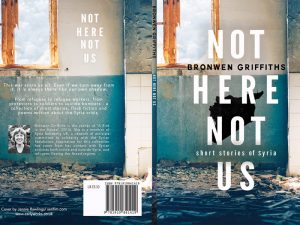

Bronwen Griffiths’ short story collection ‘Not Here, Not Us – short stories of Syria,’ was recently published by Earlyworks Press. She is also the author of ‘A Bird in the House’ (Three Hares publishing, 2014). She loves walking in deserts, and taking photographs of leaves. She has recently written a novel about refugees, and a novella narrated by a guard and his female prisoner.

Bronwen’s author website is at: http://bronwengriff.co.uk

She can be found on twitter at: https://twitter@BronwenGriff

Category: On Writing

Great post! Bringing these stories to the world is so important, and I’m glad you’ve not only published your own book but are sharing the names of Syrian authors whose works we should read. I’ll add to that list Alia Malek, an American born to Syrian parents, who recently published “The Home That Was Our Country,” a powerful account of the author’s return to her family’s home in Damascus.

Thanks Jennifer – and I will get a copy of Alia Malek’s book.