Writing Through Despair

One night, around the midpoint of writing my novel, I hit rock bottom. I’d wrestled all day with a plot problem I couldn’t solve. There had been no days off for months, my back was agony, my eyesight was blurred. Some awful compulsion was forcing me to continue doing the one thing I had proved I could not do — writing the damn novel.

One night, around the midpoint of writing my novel, I hit rock bottom. I’d wrestled all day with a plot problem I couldn’t solve. There had been no days off for months, my back was agony, my eyesight was blurred. Some awful compulsion was forcing me to continue doing the one thing I had proved I could not do — writing the damn novel.

I hadn’t just hit a wall, I was buried under one. That night, I went down for dinner and announced to my husband that I’d decided to give up on the book. I chopped tomatoes and onions, cried a little into my bowl of Cod Provençal, binge-watched ‘Love’ on Netflix, and went to bed. I was giddy with relief, and sick with fear. I was done.

Writing my novel seemed to be a matter of finding the right balance between caffeine and self-doubt, but that was the moment I plummeted between those two high wires straight into despair. I tried reminding myself of Sylvia Plath’s journal entry: “If I want to write, this is hardly the way to behave – in horror of it, frozen by it.” But even that didn’t do any good, because I had no idea how to un-freeze myself.

At the start of the project I’d ‘borrowed’ a mug that belonged one of my daughters, which happened to be the perfect size for coffee, and had these words inscribed on it: “What would you do if you knew you could not fail?” I’d taken to filling it first thing every morning before starting work. It became a kind of talisman, reminding me that my novel was my answer to that question. But what really had to learn was this: if you set out to write a novel, failure is an essential ingredient.

The morning after I ‘quit’, the protagonist of my novel woke me up, as she often did. Lines she wanted to say percolated through me while I slept, then announced themselves inconveniently at 4am. That morning was no different. As usual, I hauled myself out of bed, started up my computer before I could remind myself I’d turned my back on all that. It was as simple, and as difficult, as that. I was still frozen, still horror-struck. But I went back to work in spite of this, knowing that the greater pain lay in quitting.

Later that day, I went in search of companions in misery. I found William Goyen: “This happens to writers when there are dead spells. We die sometimes. And it’s as though we’re in a tomb; it’s a death. That’s what we all fear, and that’s why so many of us become alcoholics or suicides or insane – or just no good philanderers.” I found this, from Kafka’s journal: ‘7 February. Complete standstill. Unending torments.’ I read that line over and over again, relieved. There wasn’t something wrong with me in particular; I’d simply been cursed in the way all writers are cursed. That evening I found myself googling ‘Jane Austen first drafts’ consoled by the discovery that her first attempts also needed heavy editing. I turned to Kafka’s journals again, and noted this down: “Occasionally I feel an unhappiness that almost dismembers me, and at the same time am convinced of its necessity and of the existence of a goal to which one makes one’s way by undergoing every kind of unhappiness.”

My protagonist, Frannie Langton, is a young Jamaican woman in Georgian London accused of killing her employer and his wife, with whom she’s been having a twisted love affair. I’d never seen a black character like her in historical fiction before: educated, passionate, angry, and in love. I wanted to put her there. I had the dismembering unhappiness but, luckily, I also had the goal, the sense of urgency that kept pulling me to the work. Novels are fueled by questions, so I spent a lot of time thinking about the one that had driven me to write in the first place: Why couldn’t a black woman be the star of her own gothic romance? I sat down and wrote out a series of additional questions, taped them to the wall: Why you? Why this book? Why now?

The only cure for the despair was to write my way through it. It was a question of endurance, and of preparing to endure. It took me months to solve the plot problem, but I started by writing what I could, working my way back to it. Much of what I wrote during those months ending up being thrown away. But I don’t consider any of that effort wasted; it was the novel teaching me how to write it. I focused on the things I could control, trying to create some comfort and routine in my writing habits, devising little tricks and treats to keep me at the desk: the best coffee I could find; playlists; exercise breaks. I taught myself to tolerate the dismembering unhappiness in service of the goal. And, day by day, my draft got done.

—

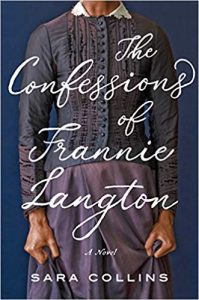

Sara Collins is of Jamaican descent and worked as a lawyer for seventeen years in Cayman, before admitting that what she really wanted to do was write novels. She studied Creative Writing at Cambridge University, winning the 2015 Michael Holroyd Prize, and began to write a book inspired by the idea of ‘writing a Gothic novel where the heroine looked like me’. This turned into her first novel, The Confessions of Frannie Langton.

THE CONFESSIONS OF FRANNIE LANGTON

“A stunning debut. . . . I love this book.” –Guardian

“A stunning debut. . . . I love this book.” –Guardian

“Reminiscent of Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace . . . [a] devious, richly detailed debut.” –O: The Oprah Magazine

A servant and former slave is accused of murdering her employer and his wife in this astonishing historical thriller that moves from a Jamaican sugar plantation to the fetid streets of Georgian London—a remarkable literary debut with echoes of Alias Grace, The Underground Railroad, and The Paying Guests.

All of London is abuzz with the scandalous case of Frannie Langton, accused of the brutal double murder of her employers, renowned scientist George Benham and his eccentric French wife, Marguerite. Crowds pack the courtroom, eagerly following every twist, while the newspapers print lurid theories about the killings and the mysterious woman being tried at the Old Bailey.

The testimonies against Frannie are damning. She is a seductress, a witch, a master manipulator, a whore.

But Frannie claims she cannot recall what happened that fateful evening, even if remembering could save her life. She doesn’t know how she came to be covered in the victims’ blood. But she does have a tale to tell: a story of her childhood on a Jamaican plantation, her apprenticeship under a debauched scientist who stretched all bounds of ethics, and the events that brought her into the Benhams’ London home—and into a passionate and forbidden relationship.

Though her testimony may seal her conviction, the truth will unmask the perpetrators of crimes far beyond murder and indict the whole of English society itself.

The Confessions of Frannie Langton is a breathtaking debut: a murder mystery that travels across the Atlantic and through the darkest channels of history. A brilliant, searing depiction of race, class, and oppression that penetrates the skin and sears the soul, it is the story of a woman of her own making in a world that would see her unmade.

Praise for The Confessions of Frannie Langton

By turns lush, gritty, wry, gothic and compulsive, The Confessions of Frannie Langton is a dazzling page turner. With as much psychological savvy as righteous wrath, Sara Collins twists together the slave narrative, bildungsroman, love story and crime novel to make something new.’ Emma Donoghue, author of Room

‘A book of heart, soul and guts…beautifully written, lushly evocative, and righteously furious. Frannie might be a 19th century character, but she is also a heroine for our times’ Elizabeth Day, author of The Party

‘A seductive and entrancing read, with captivating historical detail…The Confessions of Frannie Langton is an extremely powerful book that resonates long after the final page has been turned.’ Laura Carlin, author of The Wicked Cometh

‘I usually pick proofs up, read the blurb, maybe read a few pages… and that is usually that. This time, I started reading it – and then I couldn’t stop. Sara Collins has created a tough, fiery, vividly alive character. Beautifully written, in crisp and careful prose; but more than that, it comes across as a story that’s been waiting to be written for a very long time…[Collins] has picked up the tradition of gothic fiction and made it brand new.’ Stef Penney, author of The Tenderness of Wolves

‘I loved this novel. A literary page-turner, an engrossing murder mystery, and a deep meditation on freedom, choice, and what it means to have a voice, Sara Collins’ writing is as seductive as it is elusive – just like Frannie Langton herself. For all its horrors, I could have dallied in this opium-addled world with Frannie endlessly, another addict, hooked on Collins’ words.’ Rebecca F. John, author of The Haunting of Henry Twist

‘I loved it…Not only a good read but an important book, reminding us of both how far the world has come and how little it has changed. I was gripped, amused, and saddened. I ate Sara Collins’ words up as though they were the sugar, or laudanum, that she writes about so evocatively. It’s a glory of a book.’ Stephanie Butland, author of Letters To My Husband

‘An extremely powerful book that resonates long after the final page has been turned’ Laura Carlin, the author of The Wicked Cometh

‘A spectacular, dark novel, with elements of Jane Eyre and Paradise Lost’ Natasha Pulley, author of The Watchmaker of Filigree Street

‘What an extraordinary, exhilarating and fiercely intelligent book. I loved Frannie and she felt so very real and alive to me’ Cathy Rentzenbrink, author of The Last Act of Love

‘Frannie Langton is a unique literary creation in this pitch-perfect gothic novel: a Jamaican former slave who is both the heart and heroine of the story. I loved this moving, beguiling, gorgeously-written book.’ Kate Riordan, author of The Stranger

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Two things I’ve learned during my writing journey is that it’s unrealistic to expect a first draft to be perfect; and, second, that editing and polishing my work is immensely rewarding.