Writing Without A Plan

I did not come to creative writing with a plan.

I did not come to creative writing with a plan.

I had moved between the worlds of books and design in past lives: as a book editor at several publishing houses in New York City and — after years of study at Parson’s School of Design — designing interiors in the New York metro area. When my design business took a nosedive during the Great Recession, I began experimenting with creative writing at the nearby Sarah Lawrence campus in Bronxville, New York.

We met once a week in “the library” of a cozy house on campus. With seven other students and a teacher to guide us, our first assignment, which is still memorable to me, was to be a fly on the wall in a public space — a café, a bookstore, any place where we could listen in on conversations. We were asked to write a brief story, using dialogue exactly as we heard it, to learn just how people really speak.

It turns out, we speak in incomplete sentences. We talk over each other. Our words often don’t mean what they say. I propped myself on a red plastic barstool with a tiny notebook hidden on my lap and I studied a local diner. I took in the sounds of knives chopping on wood, noticed eye contact, or lack of, and the conversations flying. Years later, my story, “The Diner,” was published, based on this first exercise.

On the second week, the teacher asked us to write about a painful event or memory. She discussed the issue of confidentiality. Nothing read in class was to be shared outside. I felt safe. I sat down with paper and pencil on that second week, and a visual memory surfaced. I saw my mother standing by the calabash tree in the patio of my childhood home in Panama. Her eyes were blank and unseeing. Her beautiful bearing — she had gorgeous posture — had collapsed. I was 5 or 6 years old. My mother had received insulin-based shock treatment at a psychiatric hospital, though of course I didn’t know this at the time. It was hard to stop writing after that.

I had no prefabricated intention to write about myself or my family. But the gates had opened up. This memory that I called “Mami” was later accepted by the literary journal, The Westchester Review. Spare and image-driven, “Mami” became the model of what was to come.

I wrote what I could reimagine. I tried to access lived experiences. I wanted the purest truth, though memory, we know, is a chameleon. I became fascinated with the texture of memory, the voices, smells, the heavy, humid air, the sharp pang of feeling. I discovered a motherlode of powerful emotion at a time when my current life was stable and uneventful, my kids grown and flown the nest.

In those days, Skype had become popular and gave me easy access to my sister and two brothers in Panama. We compared details of stories remembered. We learned about each other and our different memories of mami.

“Había algo que no te dejaba florecer,” my sister said in her poetic way, explaining something indefinable. Loosely translated, this means, “There was something that stopped a flowering in me.”

“Matraca,” she and I said on the same beat, noting the small wooden ratchet used for percussion. It repeats it’s clackety sound as long as you continue to twirl it. Mami, eyebrows pressed together in distress, chased us with questions and disparaging invectives right up to the bathroom door where the only solution was to slam and lock the door and pray that it would stop.

My youngest brother recalled walking alone when he was 4, leaving the house and walking about 5 blocks for my grandmother’s apartment. He described laying his head on our grandmother’s lap while she stroked his back in comfort. And it was this renewed intimacy with my sister and brothers was the greatest gift of writing my memoir.

When I was in the zone writing, I discovered I was hearing a certain kind of music, the rhythms of English and Spanish intertwined, a tango of opposing forces that complemented each other. Every syllable was a beat. One word led to the next. I was not the kind of writer who starts with “a shitty first draft,” where you “vomit the words” and rewrite many times after. For me the images and their meanings were crafted in the slow layering of words and the sounds they made.

Though it took years to write what is now a complete book, I was driven to continue by a deep-seated need to make sense of my mother. Who was she underneath the anxiety that punished her as much as it punished us? And just who was I? The memories became a path to discovery, and I couldn’t let go.

—

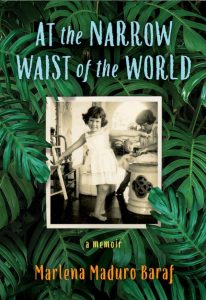

Marlena Maduro Baraf was born and raised in Panama, but chose to leave her native country for the United States in her late teens, gaining citizenship years later. She worked as a book editor at Harper & Row Publishers and McGraw-Hill Book Company, is a devoted alumna of the Sarah Lawrence Writing Institute, and has established her own design studio. Over the past 10 years, Baraf has dedicated herself to the compelling art and craft of writing. Her memoir “At the Narrow Waist of the World,” is out Aug. 6, 2019 (She Writes Press).

Find out more about her on her website https://www.breathinginspanish.com/

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/marlenabaraf

At the Narrow Waist of the World

Raised by a colorful family of Spanish Jews in tropical and Catholic Panama of the l950s and 1960s, Marlena depends on her many tíos and tías for refuge from the difficulties of life, including the frequent absences of her troubled mother. As a teenager, she pulls away from this centered world—crossing borders—and begins a life in the United States very different from the one she has known.

Raised by a colorful family of Spanish Jews in tropical and Catholic Panama of the l950s and 1960s, Marlena depends on her many tíos and tías for refuge from the difficulties of life, including the frequent absences of her troubled mother. As a teenager, she pulls away from this centered world—crossing borders—and begins a life in the United States very different from the one she has known.This lyrical coming-of-age memoir explores the intense and profound relationship between mothers and daughters and highlights the importance of community and the beauty of a large Latin American family. At the Narrow Waist of the World examines the author’s gradual integration into a new culture, even as she understands that her home is still—and always will be—rooted in another place.

Buy the book HERE

Category: On Writing

Here is a creative journey worth reading about. At the Narrow Waist of the World tells a compelling mother/daughter story in spare, lilting prose akin to poetry. I fell in love with all the characters in this colorful family, especially the narrator. Read it and weep, laugh, smile, and learn.