Yoga, Writing and The Liberation of Autism

Yoga, Writing and The Liberation of Autism

Photo by Nina Roberts

Julia Lee Barclay-Morton

In contemplating how to write about yoga and how it supports my writing process, I can’t help but see how yoga helped me function for decades as someone who did not know until age 57 that she was autistic with a side order of dyspraxia (which is basically spatial dyslexia).

Yoga includes meditation along with the more familiar asanas (postures). The more contemplative yoga lineages—such as my own: Kripalu—consider active asana practice as meditation in motion. Yoga postures were intended originally—according to ancient texts such as the Yoga Sutras—as a means to calm the body and mind for sitting meditation practice.

The first meditation I ever did was during a brief stint of taking yoga classes in the early 1980s. I remember vividly the sense of peace I had walking out of the class. This was because of having been led in savasana (lying on back, palms up, accompanied by a guided meditation) at the end of a challenging practice I was comically incapable of doing correctly.

While I did not continue going to this class when life got too busy (more fool me), I did have a sense memory of it; so, when my life became emotionally out of control in the mid 1990s, I reached back to the memory of that guided meditation. I remembered the yoga teacher saying, “if you have thoughts, you don’t have to push them away, but you don’t have to hold onto them,” and my first recovery sponsor in 1987 saying “there is no such thing as a good or bad meditation.” Those memories were enough to guide me as I sat on the sofa for 20 minutes, with a cup of coffee.

I closed my eyes and for a few moments in there, I did not push away or hold onto thoughts and felt a moment of profound peace. When I woke up the next day, I did it again. And the next day and the next. I have been meditating every day ever since, which is by far the most disciplined part of my life. This gentle practice is what guided me out of the abusive relationship I was in at the time, by giving me the space to find my own voice as a writer. (When I discovered my first play was getting published, my then husband decided to leave. I was devasted at the time, but of course this was a jail break. I had taken back my soul, which meant he had lost control.)

After he left, I discovered Kripalu yoga, and the concept of witness consciousness—that part of us that hears our thoughts and feels our feelings, but is not swamped by them. A five-part practice of breathe, relax, feel, watch, allow led to my ability to allow feelings of hurt and rage pass through me, so I could grieve and heal the time I had spent with a person who had been so damaging to my psyche.

Alongside all this was my writing coming out into the world. First, my stage texts, written as a theater director who wanted to find a way to create texts I could use without concern for another writer’s feelings to create what I envisioned more fully; these texts are more maps than the territory, so they can be inhabited and co-created with collaborating actor-artists.

As I began going to actual yoga classes, I had to face a lot of insecurity I had about my body and my inability to follow any instructions about how to move, which I now know is caused by dyspraxia, a developmental issue I have suffered from since childhood, long before it was ever even defined as an issue. Dyspraxia manifests as being clumsy and being unable to learn dance steps or follow physical directions. I panic and can’t take it in. Because I seem intelligent otherwise, people get frustrated with me, making it even worse. I have spent my whole life with mysterious bruises on my body from bumping into things, but it’s such a common experience, I have forgotten what happened by the time I see a bruise.

My yoga practice was therefore hard to embody, and I had to endure feeling ridiculous in public as a grown-ass woman seemingly unable to take basic instruction. However, eventually I did teach my body the postures over a number of years, at which point they became embedded, along with a philosophy that one should listen to one’s own body and not attempt to look like a model in Yoga Journal. At 56, I decided to become certified in Kripalu yoga teaching, because this gentle practice had been so healing, and I wanted to ensure the lineage continue. This intensive training, which included living in close proximity to a lot of people for a month, led to my autism diagnosis.

Dyspraxia is a common autistic experience, but being autistic also leads to a sense of not knowing what is going on socially amongst neurotypicals, and I began to see even as I was healing deep trauma that I still felt on the outside of any group. As I have learned in the 18 months since my diagnosis at age 57, autism is a different neurotype not a defect; it’s disabling because of how we are misunderstood by the allistic world. The experience of being an undiagnosed autistic person is one of extreme alienation and insecurity, which in my case has been alleviated by self-understanding and connection with other adult autistics, who as it turns out are great and easy to communicate with, because we understand each other. I no longer feel so alone.

Yoga helped me get to this point, which leads to feeling much more confident in my own words. The variety of voices in my work and use of multiple genres makes a lot more sense knowing I am autistic. I am now much more at ease with who I am and what my writing is doing in the world. While the autism diagnosis is a relatively new development, it is amazing how quickly it has made everything make sense.

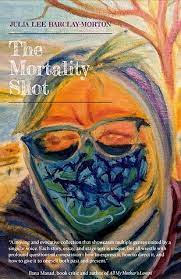

My book that has just been released, THE MORTALITY SHOT, is a hybrid collection that includes all my writing voices, creative non-fiction, stories, and a stage text. It bridges the time before both COVID and my autism diagnosis, when the grieving I was doing was for other people who were dying, and then through to my own struggles with COVID and long-haul COVID, both of which I survived because of yoga. The breathing techniques got me through acute COVID and then helped heal long-haul COVID with more subtle postures and breathing that activate the vagus nerve, which is a key regulator to the nervous system. As it turns out, this is a key issue especially affecting long-haul symptoms. My training in all of this led me to the healing modalities I needed. Without that, there would be no writing.

Our Kripalu yoga teacher trainer Rudy reminded us continually that we needed to “strengthen the container” and that is what yoga does. It makes our bodies more resilient in a deep way. That doesn’t mean I don’t also get vaccines and go to doctors, which I need to do, especially after long haul COVID landed in my hospital with a TIA and dissection in my carotid artery, but the yoga is what makes it possible to heal.

As for the writing itself, I don’t write before I’ve meditated, and either before or after my writing practice, I do an active yoga practice. This ensures my body, mind and emotions don’t become too sclerotic. I have since added cardio to the mix, which has been energizing, but this too is only possible because of the yoga healing my body and mind enough to make more activity possible.

So, in the end, the question of what does yoga do to support your writing is a little like asking what does oxygen do to support your breathing. It’s integral. Without it, there isn’t any me, never mind any writing.

—

Julia Lee Barclay-Morton, PhD is an award-winning writer/director, whose writing has been produced and published internationally; her first book, a hybrid collection, THE MORTALITY SHOT is out now with Liquid Cat Books; recent publications in Prairie Schooner, [PANK], Heavy Feather Review, and, as winner of Nomadic Press Bindle Contest, chapbook of White Shoe Lady. She founded Apocryphal Theatre when in London (2003-11); all of her experimental stage texts were recently streamed in a 22-hour radio project created with Viv Corringham, commissioned by Radio Art Zone. She lives in NYC with her husband and cat, where she coaches writers, paints, makes theater, and teaches yoga, while working on a hybrid memoir about being diagnosed on the autism spectrum at 57. More at TheUnadaptedOnes.com

Insta: @julialeebarclayauthor

Twitter: @wilhelminapitfa

Website: https://www.theunadaptedones.com

THE MORTALITY SHOT

THE MORTALITY SHOT is a hybrid collection of stories, essays, and experimental stage text that meditates directly or indirectly on mortality. Julia wrote the earlier work in the collection about grieving others’ deaths; more recent pieces include facing her own mortality thanks to long-haul COVID complications that landed her in the hospital.

THE MORTALITY SHOT is a hybrid collection of stories, essays, and experimental stage text that meditates directly or indirectly on mortality. Julia wrote the earlier work in the collection about grieving others’ deaths; more recent pieces include facing her own mortality thanks to long-haul COVID complications that landed her in the hospital.

“These stories and essays (plus a stage text) push up against heartfelt questions of life and death in ways that are complex, counter-intuitive, humorous and striking. Writing against the grain, in varying styles and intensities, The Mortality Shot goes places that so much current literature wouldn’t dare, demonstrating that real writing is always a risk and a gamble, and that only through taking such risks can we get at the things which truly matter.”

– Jacob Wren, author of Polyamorous Love Song

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips