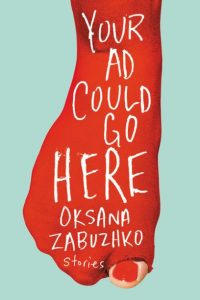

Your Ad Could Go Here

Oksana Zabuzhko has been called a Ukrainian combination of Susan Sontag, Adrienne Rich and Rachel Maddow, and her novels have received international fame. Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex caused the biggest literary scandal in Ukraine in decades. Since its publication in 1996, it spent 10 years at #1 on the Ukraine’s bestseller list; has been translated into 16 languages; and is recognized both as the calling card of the new Ukrainian literature and “Bible of Ukrainian feminism.” The Swiss newspaper, Tages-Anzeiger, called her follow up novel, The Museum of Abandoned Secrets, one of the “20 Best Novels of the 21st Century” (along with The Corrections, Harry Potter, and Atonement), and this book has been compared to the finest works of Thomas Mann, James Joyce, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Oksana Zabuzhko has been called a Ukrainian combination of Susan Sontag, Adrienne Rich and Rachel Maddow, and her novels have received international fame. Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex caused the biggest literary scandal in Ukraine in decades. Since its publication in 1996, it spent 10 years at #1 on the Ukraine’s bestseller list; has been translated into 16 languages; and is recognized both as the calling card of the new Ukrainian literature and “Bible of Ukrainian feminism.” The Swiss newspaper, Tages-Anzeiger, called her follow up novel, The Museum of Abandoned Secrets, one of the “20 Best Novels of the 21st Century” (along with The Corrections, Harry Potter, and Atonement), and this book has been compared to the finest works of Thomas Mann, James Joyce, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Now, Oksana Zabuzhko makes her triumphant return to U.S. publishing with the passionate short story collection, YOUR AD COULD GO HERE and we are delighted to feature one of the stories on our site!

Your Ad Could Go Here

Translated by Halyna Hryn

They were the most splendid leather gloves I had seen in my life: finished to the gossamer weight of a rose petal, with a dazzling, luminous bay hue that instantly brought to mind the Imperial horses and their silky croups at the Hofreitschule, delicately laced with a finely cut design at the wrist (all of it handmade, my goodness!), they immediately wrapped my hand in the firm loving grasp of a second skin, and one was compelled henceforth to stroke the hand thusly gloved with the same reverence as an Imperial steed. One wanted to stroke and admire the hand, spreading one’s fingers against the light, making a fist and letting it go—Ah!—and never take such beauty off. In a word, walking away from those gloves was beyond my power.

They existed—as befits any work of art—as a singular artifact. Everything in that glove shop was singular, not one pair resembled another, each more fantastic than the next, but these—these caught my eye the second I walked through the door, like the glance of a dear fellow creature in a crowd. And they were exactly my size: I told the gentle old man in a knitted vest who sat behind the counter I wore a size six, but he just shook his head. No, he said in his slightly raspy Viennese English, you’re not a six but a five and a half, here, try these. But I always buy sixes! You’ll be telling me, miss, he laughed, I’ve been making these gloves for fifty years. Oh, you make these? And sell them? So you are the owner? Yes, he confirmed, with the quiet pride of a master craftsman who knows his worth. The tiny store on Mariahilferstraße, which I entered on a whim with a purely touristy I wonder what’s here? transformed into a fairy-tale forest hut—the one to which the fleeing heroine stumbles at nightfall and where she meets the master of the underground kingdom who chops his own wood, carries his own water, and makes his own supper. I dearly wished I spoke better German—and the old man, better English—we could hardly talk about anything important with our tourist-minimum vocabularies. I adore such dapper gentlemen in vests—in my own country they were exterminated as a species fifty years ago, shipped out to Siberia in cattle cars, and their absence from the universe in which I grew up was still evident—as visible as silhouettes cut out of group pictures, with the names written underneath. It warms my heart every time I see what became of them in other, less chaotic lands. To spend fifty years sculpting such gloves, from tanning and cutting to the finishing stitches around the eyelet holes that would adorn imaginary hands—does this not mean becoming the Lord of Gloves, the one and only, not just in Vienna, but in the whole wide world?

I named them my sunshine gloves—they glowed. I could see their aura in the paper bag into which the Lord of Gloves packed them for me—with his name imprinted, and the address—Mariahilferstraße, 35—and the telephone numbers (landlines—everything about him was so Old Worldly, solid, with a distant nineteenth-century breeze of faith in an ordered world, a world in which things are made to last forever because the makers know that things outlast people and will one day serve for our descendants as the only tangible proof of our existence). Even through the paper bag, I could feel the silky softness of the rose-petal leather. I kept touching it and smiling. I had been entrusted with a treasure, in the fairy-tale forest hut—a talisman from a different age. Who today would labor over such gloves—every pair unique, every pair a single copy—to sell them for those same fifty euros they charge for the thick chunks of mitts in the mall across the street?

Later I got myself a special designer sweater to go with the gloves. A special jacket. A special pair of fine suede pants. I had the persistent feeling that my sunshine gloves stood out no matter what I wore, no matter how carefully I selected it, and they most certainly did: they demanded different lines—designed by someone in love with their model. With the gloves, I could tell the mood with which another item of clothing was conceived and made: they accepted some, but rejected other garments without any apparent logic, but irrevocably and at once. In the fall of 2004 they suddenly fell in love with a flamboyant fiery scarf, which I then wore throughout the entire Orange Revolution—never mind that the scarf did not come from a fashion designer and cost a third of what the gloves had. They were perfect together, and press photographers all to the man wanted my picture in that orange scarf and my sunshine gloves—No, no, don’t take them off, just leave everything as is!

Here one rather expects a certain development of the plot: Julio Cortázar, for instance, or even Peter Haigh would have definitely written a story (and Taras Prokhasko would have told one in a pub, being too lazy to write it!) in which the gloves quietly move on from approving garments to approving—or disapproving—people and begin to rule the heroine’s life, guiding her to the authentic and away from the fake, sweeping out from her life’s wardrobe false friends, unnecessary obligations, and ultimately her own masques, stripping her down like a cabbage to her bare core, and then we might discover that there is no core, that the heroine herself does not pass the test of the magical gloves, so in the end she has to perish in a dramatic fashion, to disappear, be disposed of, and the gloves, fine as a rose petal, will remain gloving in their silky-chestnut splendor on a desk, waiting for their new owner. Something along those lines.

What actually happened was different. What happens is always different from what we read about later. In May of 2005 I did what I had never, in my recollection, which begins more or less at the age of three, done: I lost a glove.

Maybe I lost it getting out of a cab. At least, it was not anywhere on the sidewalk—I retraced my steps along the entire length of my route, where I could have, theoretically, dropped it, looking hungrily into every single trash can. All in vain: the glove was gone. Evaporated. Vanished. Rose up to the sky and flew away. Took off and flew into the wide blue sky. Burned to a crisp like the Frog Princess’s skin. My sunshine glove from my left hand. The hand was left naked.

And I don’t think I wept like that since the age of three. I mean, of course, I’d cried countless times, and had abundant occasions and much weightier reasons to do so in my more or less coherently remembered forty years since I was three—but weeping like this, truly, never. I wept like the child who discovers for the first time the injustice of the world, which she had begun to believe to be orderly and safe. Adults call it a life crisis—and instead of weeping, they usually climb into a noose or call a therapist. Or look for other ways to glue together the shattered self, because the older you get, the more you see that really life can be put back together somehow, made bearable, although it will never be the way it was before, but that’s okay, it’s going to be all right, really, things have a way of fixing themselves, as long as you’re okay. That, specifically, is what everyone at home told me: Stop being a child, you have the other glove, you have the address, you have a book coming out in Austria, you’re going to Vienna anyway—stop by the store and just ask them to make you a new one! You could even send them the right one by mail, my husband said, call them, make the order, and have the left one ready for pickup when you’re there. There was no way I was doing that, though, no mailing—for me, that was somehow out of the question. To pass the surviving glove into unknown hands, to entrust its fate to a faceless tracking system felt like a betrayal to me, as if I would be confirming I deserved to have been abandoned by the lost glove, as the folk song goes, “You knew not how to honor us . . .” No, I had to do it in person, I had to face the Lord of Gloves in his forest hut at Mariahilferstraße. One step into a side street off the busy shopping thoroughfare, push the right door—and I will be again in that cozy, draping silence, green colored, as if tinged with the virgin forest outside the windows but in fact because of the green lining the display case, filled with the gorgeous, one-of-a-kind pairs of gloves in liver-bay, black, buckskin and roan. Perhaps the Lord of Gloves will offer me tea and we will have a chance to converse a bit, about important things—such as pursuing his craft for fifty years, despite the rising flood of Mariahilferstraße outside his windows. I memorized several particularly difficult phrases in German, in case he couldn’t understand my English.

The prospect truly made me nervous.

On that trip, I barely had an hour to spare in Vienna and had to fit in the trip from Hotel Mercure, near the Westbahnhof, to Mariahilferstraße and back. So I started dialing the numbers listed on my paper bag (in which I carried the right glove) as soon as I landed and kept calling until the cab came to pick me up at the hotel. There was no answer on either line. I felt a sick knot in my throat; my heart hammered. In forty minutes, I was due for an interview with a reporter from a popular weekly, back in my hotel’s lobby. At least I long memorized everything one says to a reporter about one’s book, in well-polished blocks of text, like an audio guide—please press ten now. It was fall, the air beaded with moisture, and early lights glowed along the inappropriately festive Mariahilferstraße. I wore the same tweed coat I had on the day I lost the left glove. Here? The driver asked. Here, I said: at least the door was where it should be, I was looking straight at it.

Nothing else, however, was there.

It was like coming home at night, opening the door with your key, and seeing someone else’s apartment, with entirely different furniture, long inhabited by strangers who, disturbed, turn to face you in alarm. There were scarves, and belts, and some high-tech home decor, plastic, not wood. Different lighting, vertical cubical display windows, everything a sterile white, a crowd of people, and a completely different smell. Instead of entering a magical parallel world, I was standing in the accessories section of a large department store. Grüß Gott, darf ich Ihnen helfen? asked a glamorous young woman with a smart haircut and fluorescent fingernails. Stammering in my English, I pulled out my paper bag, the talisman that would let me be recognized at the entrance to the other world (What if, I’d desperately thought, there’s still another room here, and the forest hut is now there?) Desperately looking in all directions in search of a secret door (maybe behind that curtain? No, that looks like a closet . . .), I tried to explain: I had one glove, which I bought here two years ago, and I lost the other. Please, over here, the woman pointed with her blinking nails—the gloves are here! Faceless chunks of grey hung from clothes pegs like carcasses in a butcher shop. No, you don’t understand, I want one exactly like this . . . This is Roeckl, the woman repeated, and the brand name sounded piercing, like the cawing of the carrion-feeding crow—Here are our gloves! Mine appeared to irritate her, like a piece of evidence testifying to a covert misdeed in which she, too, had a part: she kept saying Roeckl, Roeckl, as if she meant Shoo, shoo! Where is the older gentleman who used to have a store here, a glove maker? I asked and Miss Crow screeched as if stung by a wasp, in German, Er ist tot! Slamming that word like a door into my face. Then, in a nicer voice, she repeated in English: The elderly gentleman has died, Roeckl bought the place.

When did that happen? I made an effort to keep down the trembling in my knees—I already knew the answer.

In the spring, Miss Crow said, sometime in May.

In May, wasn’t it. It was pointless to ask for the exact date, everything was clear: he took his glove as he was leaving, the dead sometimes do that—when they want to leave the living something to remember them by. Something more reliable than mere words.

Doors swung open and closed, a plump lady in a down jacket was asking to see a wallet, behind me a pair of Russian women chatted loudly about scarves. Passersby looked into the windows. A cell phone rang. Nothing was left, nothing to remind me. He died—he’s been disposed of. Gone to be recycled. And what about the gloves? My sunshine gloves and other, moonlight gloves (Mars gloves, Jupiter gloves, Venus gloves, Saturn gloves?)—gloves for love, gloves for mourning, liver-bay, black, buckskin and roan, that had inhabited this space so recently, what became of them? Were they disposed of at a garage sale?

Aloud I asked, trying to sound more or less composed, Wasn’t there anyone to inherit the business? Miss Crow made a face that simultaneously expressed the appropriate respect for the deceased and a barely indulgent sympathy for the total unsustainability of his business model—meaning, well, you must understand. Yes, I understood. Understanding, in fact, is my job, that’s what writers are for—to try to understand everyone and everything and put this understanding into words, finished to the gossamer fineness of a rose petal, words made supple and obedient, words cut to hold the reader’s mind like a well-made glove that fits like second skin. One can’t do this without understanding, no matter how regularly our kind appears on official paperwork under the rubric of “Entertainer” and gets paid not so much for the hours of labor but for the brand. Roeckl. The old store’s location smack in the middle of the main shopping street must’ve cost a fortune. I can imagine the bidding war that broke out after the Lord of Gloves died, the space is practically a mansion. But can anyone tell me: Is there no one left in Vienna who makes gloves like these? Is there anyone left even still alive who knows how to make gloves like these? Can it possibly be that I became witness to the death of an entire art—like one of those Pacific Island languages that disappears from linguistic atlases every year, sealing off for us, like treasure caves, the parallel worlds they give expression to?

Why didn’t he pass his craft to anyone? Why wasn’t there the right person to pass it to, another slightly crazy, bearded nerd in love with women’s hands, or simply with a girl to whom he wanted to give the most beautiful gloves in the world? One doesn’t even have to be all that crazy for this—the Lord of Gloves probably himself started there, and the girl refused him, most likely, and for the next fifty years he touched women’s hands with all his unrequited tenderness but all of us who bought his gloves dragged off, bit off a bit of it for ourselves, like hungry geese, and before we knew it, it was all gone. How could it be that no one stopped, no one asked to be taught this language? Every great master has to have students—and he was a great master, I still have proof I could show you, look at this chestnut glove I have, look how delicate and sensitive it is, like a living thing, don’t you want to try it on?

Try it! Please, girls, don’t be afraid . . . don’t run away!

No, this last line is me making things up, that didn’t happen. I didn’t stand there brandishing the master’s last surviving piece in front of the alarmed saleswoman and did not deliver a fiery oration that would scare the customers (although we could have yet another short story here, in which the heroine is taken away by the police, a little Hollywood, a little homage to Woody Allen, but squarely in a feminine sensibility—why not, the sixties are coming back, female rebellion is trending). Instead, I politely purchased from Miss Crow a pair of her mass-produced mitts in a less-than-acidic color (and never wore them): it was my way of paying her for the information. Then I walked, without seeing where, along Mariahilferstraße, stumbling—Entschuldigen!—into other pedestrians’ bodies and thought, swallowing tears mixed with rain, I could write a story! Oh, what a story I could write—winged and sure footed, as if dictated by heaven itself, I could go lock myself in my hotel room right now, and write it—if I didn’t have the interview to go to, and then my reading in the city library, and then a dinner with the organizers, and my flight at the crack of dawn—the usual schedule of our literary marketplace. I, too, work regular retail. The Lord of Gloves was mistaken to trust in me.

And you, too, should forget everything just read here. One day, someone will erase all of our scrupulously crafted words from their electronic depositories in order to save some space, and on the white screen of the new and improved supergadget of fall 2063 we will see the flashing slogan that already so often covers up the vacant spaces of bricked-up doors:

YOUR AD COULD GO HERE

Oksana Zabuzhko, author of “the most influential Ukrainian book in the fifteen years since independence,” Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex, returns with a gripping short story collection.

Oksana Zabuzhko, Ukraine’s leading public intellectual, is called upon to make sense of the unthinkable reality of our times. In this breathtaking short story collection, she turns the concept of truth over in her hands like a beautifully crafted pair of gloves. From the triumph of the Orange Revolution, which marked the start of the twenty-first century, to domestic victories in matchmaking, sibling rivalry, and even tennis, Zabuzhko manages to shock the reader by juxtaposing things as they are—inarguable, visible to the naked eye—with how things could be, weaving myth and fairy tale into pivotal moments just as we weave a satisfying narrative arc into our own personal mythologies.

At once intimate and worldly, these stories resonate with Zabuzhko’s irreverent and prescient voice, echoing long after reading.

Buy the book here

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing