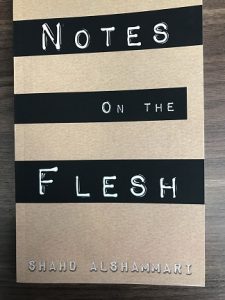

Notes on the Flesh: An Arab Disability Narrative

“The MRI itself was an uncanny and strange experience. I had never been in that machine –it was very much like a white coffin. You get wrapped up in a blanket, like a baby, or a dead baby…Whatever happens, you cannot move” (Alshammari, 39)

“The MRI itself was an uncanny and strange experience. I had never been in that machine –it was very much like a white coffin. You get wrapped up in a blanket, like a baby, or a dead baby…Whatever happens, you cannot move” (Alshammari, 39)

There is usually a strong and clear distinction between academics and creative writers. Rarely do the two merge in one. I teach literature and find myself identifying strongly with being a scholar of Disability Studies and Women’s Studies. My research has always been invested in madness and disability in women’s literature.

What do different experiences do to one’s understanding of life? How to navigate? I had read many books by British novelists (as my interest was initially Victorian literature) and branched out to read works by Indian writers, South-African, and international writers. My issue was finding portrayals of disability and disabled protagonists in non-Western narratives. Very rarely were there any women writers that chose to write center a narrative around a female protagonist with a disability (physical or mental). In most cases, disability was invisible, the silent subplot, and if you squinted really hard, you could imagine that the author was not employing negative connotations of disability.

Given that my scholarly interest was disability and women, I found myself reading Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals. Lorde’s insistence on writing about her illness and the journey through self-care and healing not only inspired me, but also, it left me feeling responsible both to myself and others who did not have a voice. Lorde’s work soon became the companion I needed into my journey through illness and life.

I was living with Multiple Sclerosis and had found myself confused not just by own body’s limitations, but also by society’s stigmatization of women with disabilities. I didn’t find any texts about an Arab woman who journeys through illness and comes out of it alive. Notes on the Flesh was written over a span of three years. As the title suggests, it is concerned with what happens to vulnerable bodies, to love when disability threatens to rupture bonds between two lovers, and to women who become victims of patriarchal definitions of “ideal femininity.”

Love, whether Western or Eastern, Arab or non-Arab, is a universal theme. How lovers interact and deal with boundaries between women and men, women and women, is what becomes specific to different cultures. Fleshing out these differences was part of the journey of my narrative. How different are experiences of love, disability, and pain across cultures? What are the power dynamics at hand, and how powerful are these female protagonists in comparison to their male counterparts?

The book alternates between female and male protagonists, not following a chronological order but rather shifting between different voices in pain, vulnerable, and in love. Who is not vulnerable in love? Who is not, at one point or another, helpless in the face of love? And yet, that desire to love and be loved fully, irrevocably, seeps through the body and Notes on the Flesh: “There is something beautiful about having someone witness your life’s journey. A witness to pain, a witness to pleasure. The silence, leaning against the wall, watching, observing, knowing when to speak, when to breathe” (Alshammari, 64).

Notes on the Flesh examines this very connection between self-love and one’s vulnerability in love. Some of the characters are star-crossed lovers, unable to consummate their love because of society, religious differences, or failing bodies. Everything is written on the body – the body speaks and cries out in agony, in a desire to diagnose society’s disorders. It is not the body that needs to adapt to society, but rather, society that needs to be acceptant and more accommodating.

Notes on the Flesh examines this very connection between self-love and one’s vulnerability in love. Some of the characters are star-crossed lovers, unable to consummate their love because of society, religious differences, or failing bodies. Everything is written on the body – the body speaks and cries out in agony, in a desire to diagnose society’s disorders. It is not the body that needs to adapt to society, but rather, society that needs to be acceptant and more accommodating.

“I wondered if there was really something wrong with my brain, if I really had a tumor, could it be something that was causing my brain to rot? It embarrassed me that I was in pain” (Alshammari, 41).

The characters in Notes on the Flesh must contend with society’s insistence on perfection, with the burdens of womanhood and motherhood, and must somehow find a balance between vulnerability and power. Familial bonds are part of the larger oppressive structures of society; family members struggle to accept the presence of illness. Illness is labeled as the antagonist by the characters, yet it is precisely society to blame. This work is a slim volume of stories, both fictional and nonfiction, that will hopefully attract those interested in love, disability, women’s studies, and identity.

—

Shahd Alshammari is a Kuwaiti author. She also holds a PhD from the University of Kent (UK) and teaches literature.

Find out more about her on her website https://drshahdalshammari.com/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing