On Being Read: Shelf Life

SHELF LIFE

Back in the days when I thought it would be a cinch

to command a print run of, say, thirty thousand,

I used to dream of being read, dozens of readers

dawdling over every inch, dallying

with each irresistible insight.

I thought of our intercourse

as a fertile two-way street,

spurring us all onto a higher

plane of understanding. You,

reader, would

root for me, and I, purring, would give you my all —

deposit it humbly at your feet, or at

your local library.

I wondered if there would be an electric spark,

a charge

for every profitable connection made

between my promiscuous brain

and yours;

a morse-code in the dark, winking on, off —

a wild firefly cotillion.

Being read would reveal

how many soul mates I had in the world.

I’d be pelted with flowers,

sent stricken fan letters,

quoted profusely,

invited to speak to your assemblies.

I’d never be alone again. Ah,

but how could I, a virgin author,

be expected to know better? Uncracked,

untouched, not even a blip

on the literary radar screen,

I had only my daydreams to go on.

As I sat there at my desk, smitten with

some piece I had just written,

it seemed impossible that

there might not be any takers for

the fresh, ingenious thoughts I had

to offer.

One fine day, having penned that final line,

I would read it over

one last time as the public

hovered with bated breath. And then,

still clammy and glistening with the

sweat of my brow,

I would emerge from my cell

and step out into the world.

I’d be delivered of my first book, and

there would be such a stir, such rapture,

such a rush to whisk me away

into the literary pantheon,

that I would never be alone again.

The dawning has been slow.

I can now see reality

snoring in the second row; I mean, my first is still

waiting in the wings

hoping for a chance to be pushed onto the stage,

but now it has siblings crowding behind,

just as eager to have a go.

I worry about this: what if

one of the others,

younger in age but

more savvy and bold, were

to elbow its way in ahead

of my first-born? Which

would then be ‘first’?

I try not to think of my plucky

bundles, sent

out into the world in all

feckless innocence, only

never to be returned or even

stamped with the courtesy of a reply.

Some, to be sure,

did find their way home eventually,

sordidly stained,

hustled by agents who

courageously stuck their

necks out for a while

but had to give up on me in the end.

Still alone,

an old maid now, my works

wallflowers wilting on the shelf,

I am drained

of the old illusions.

Posthumous perhaps,

but in this lifetime? Not a chance in hell.

Oh, but deal with it!

Reality check:

Who wants to have her words niggled at

by cocky copy-editors, her choices derided

by a sullen jury, her meaning misunderstood —

— a target of puzzlement,

heckling, contempt, offense,

boredom, indifference

or fury?

For I know now that being read is not enough.

It needs to be done

with dedication, and with pleasure. And

being read with pleasure is not enough, there

has to be a concrete response, a positive

affirmation.

And a positive response is not enough,

it has to come from someone you respect,

because what do most people know

anyway.

Even a positive response from

someone you respect is not enough,

since you can never be sure if it is quite

sincere.

Who wants to be parachuted

around the globe anyway,

cloned creepily a thousand times over

like Charlotte’s offspring,

each squiggly thing vulnerable to

harm and neglect?

A single pristine volume hung

on the wall of some hushed museum

suddenly seems a

more sensible option. Look

but don’t touch, it ought

to read in red letters:

No yawning

No snickering

Not to be left out in the rain

Not to be read in the john

And never

ever to be remaindered for a dollar

ninety-eight.

So let me state it here,

for the record:

Being published isn’t for me. You can keep

your three-martini lunches at the

Four Seasons, your

five-city book tours, your

six-figure advances. Phooey

to your oohs and your Oprahs,

your bouquets and your Charlie Roses.

Don’t even try to woo me with Pulitzer

prizes or teaching posts, a

by-line or fame beyond my crudest

dreams. Honestly, it’s not my thing.

I’m sure I’ll

get along

fine

without it

—

Hester Velmans is a novelist and translator of literary fiction. Born in Amsterdam, she had a nomadic childhood, moving from Holland to Paris, Geneva, London and New York. After a hectic career in international TV news, she moved to the hills of Western Massachusetts to devote herself to writing.

Hester Velmans is a novelist and translator of literary fiction. Born in Amsterdam, she had a nomadic childhood, moving from Holland to Paris, Geneva, London and New York. After a hectic career in international TV news, she moved to the hills of Western Massachusetts to devote herself to writing.

Hester’s first book for middle-grade readers, ‘Isabel of the Whales,’ was a national bestseller, and she wrote a follow up, ‘Jessaloup’s Song,’ at the urging of her fans. She is a recipient of the Vondel Prize for Translation and a National Endowment of the Arts Translation Fellowship. For more info, visit her website at Hestervelmans.com.

Follow her on Twitter @HesterVelmans

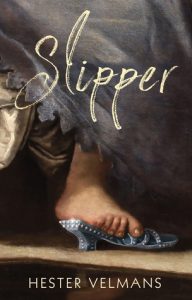

About SLIPPER

Meet the woman who inspires the author of the world’s most famous story: Lucinda, a penniless English orphan, is abused and exploited as a cinder-sweep by her aristocratic relatives. On receiving her sole inheritance—a pair of glass-beaded slippers—she runs away to France in pursuit of an officer on whom she has a big crush.

Meet the woman who inspires the author of the world’s most famous story: Lucinda, a penniless English orphan, is abused and exploited as a cinder-sweep by her aristocratic relatives. On receiving her sole inheritance—a pair of glass-beaded slippers—she runs away to France in pursuit of an officer on whom she has a big crush.

She joins the baggage train of Louis XIV’s army, survives a horrific massacre, and eventually finds her way to Paris. There she befriends the man who will some day write the world’s best loved fairy tale, Charles Perrault. There is much more: a witch hunt, the sorry truth about daydreams, plus some truly astonishing revelations, such as the historical facts behind the story of the Emperor’s new clothes, and a perfectly reasonable explanation for the compulsion some young women have to kiss frogs. This is not the fairy tale you remember.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing