A Treasure of Letters

Years ago, I discovered a trove of letters in my backyard.

I had just become the owner of an old house and when I went to clear out the weed-choked yard, I found, hidden in a broken-down shed, a steamer trunk. The trunk was sagging with rot but still tightly closed and sealed. When I opened the trunk, treasure spilled out. Hundreds and hundreds of letters.

But whose letters were they?

Along with the bundles of letters, I found glass plate photographs of a couple sitting together in front of huge waterfalls. The woman wore a bonnet and the man had a tightly curled mustache. Digging further, I found a box with the actual straw bonnet worn by the woman in the photograph. Who was this woman? I found newspapers announcements for a wedding: Addie Bernheimer married Dewitt Seligman on June 5, 1878. For their honeymoon, they went to Niagara Falls.

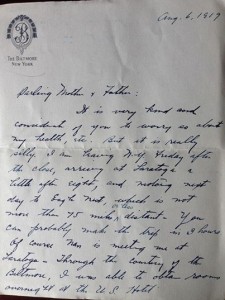

The letters in the trunk belonged to Addie. Most of the letters had been written by her son, James. He was her only son, and youngest child. When he was at Princeton, from 1908 through 1912, James wrote to his mother almost every day, and sometimes twice a day. When I first read those letters, I developed a bit of a crush on James. He was so funny and sweet, and affectionate. Every letter was signed, your loving son.

When my oldest son was leaving for college, I went back to the letters of James Seligman and found that my feelings for the young man had changed. Now I felt a maternal pride – what a good boy, to write to his mother so often – and also a tiny surge of anxiety: would my son write letters to me? We live in a digital age, and I know I could expect texts and the occasional email. But letters?

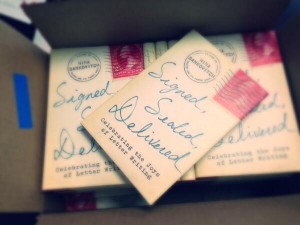

Signed Sealed Delivered by Nina Sankovitch

I set off on a quest to understand why I valued the letters of James so very much, and why I looked forward to receiving mail from my own son. I researched back through thousands of years of letter writing, going through my own saved correspondence, as well as university and town archives, and the personal letters lent to me by friends and published collections of letters. I set about defining the exact qualities of letters that make them so special and wrote about this quest and my discoveries in a book, Signed, Sealed, Delivered.

People have been writing notes to each other since we first learned to scribble out symbols. The Ancient Egyptians wrote thousands of letters to each other. This is amazing because only a tiny percentage of Egyptians could read or write. But when an Ancient Egyptian wanted to get a letter out, he went to the local scribe and paid to have a letter written. All of the letters written by Ancient Egyptians included the language, “It is good if the Lord takes note” – an acknowledgement of the importance of the written message and gratitude in having it read and then acted upon.

And messages didn’t only go to the living. The Ancient Egyptians wrote to their dead relatives, asking for help in the world of the living. Many of these letters offer thanks for help that is expected, and then a bit of guilt is thrown in: I did so much for you when you were alive, and now you cannot even send a bit of good my way? Clearly, the Ancient Egyptians expected that in gratitude for a letter well-written, the asked-for favor would be carried out, even from beyond the grave. The worth of a letter was so much, that an answer to all requests could be expected.

In all my reading of all the letters I’ve searched out, the most prevalent emotion, across all ages and places, is thanks. People write letters to express thanks because the effort taken in writing a letter demonstrates just how much gratitude the writer feels.

It is this quality of care that defines letters as unique forms of communication. But this is not the only quality: the privacy afforded by letters is also a singular characteristic of letters, and a valued one, when so many other forms of communication are under surveillance.

Letters are a bridge between one person and another, and also between one time in history and another. Some letters plunge us into a historical period, others preserve memories from our own times. Most of us won’t make it into the history books – but we can leave a part of ourselves behind in the letters we write.

Letters create a physical connection between correspondents. When I touch the letters of James Seligman, I am touching the pages he touched. When I send a letter to my son, I am extending my arm around his waist, drawing him in close. And a letter is proof. Proof in the legal sense, very often, and proof in the more personal sense. A letter proves that we’re here, loving and caring and thinking about the people to whom we write.

I know of a couple who have been writing letters to each other every single day for the past twenty years. What do they write about, given that they live together? They write about the big stuff: their feelings, money, God, what’s on their “bucket list.” The purpose of their letters is simple: “it’s a gift of love.” Yes, a letter is a unique gift.

There is much to be said for the speed and efficiency of communicating via email and text. But there are qualities of letter writing that still resonate with us. At the end of my journey into the history of letter writing I was surprised to realize that while the letters I wait for are certainly worth longing for, the letters I write are what matter most of all. Each letter starts a connection, creates a history, lays the first stones of a bridge, extends a hand.

—

Nina Sankovitch is the author of Tolstoy and the Purple Chair, and the newly-released book, Signed, Sealed, Delivered: Celebrating the Joy of Letters

Follow her on Twitter at @ReadAllDay. Subscribe to Nina Sankovitch’s blog at Read All Day.org. Like Nina’s Tolstoy and the Purple Chair Facebook Page and her new page Signed, Sealed Delivered to keep posted on new events and share your support!

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, US American Women Writers, Women Writing Non-Fiction

This is lovely.

Letters written, received and letters found are a treasure. I loved this article and agree with all of it. When I write fiction, I start out by writing letters from one of my characters to the other. My upcoming novel, Return to Sender, is based on letters, my other novel (in the works) is titled, Esmee’s Letters. I’ve long had a fascination with letters.

What a lovely and precious gift you received in that trunk. I miss the art of letter writing as well and admit I fall pray to the “quick and fast” of a jotted email all too often. Lovely post.