An Intangible Legacy By Meera Ekkanath Klein

An Intangible Legacy

By Meera Ekkanath Klein

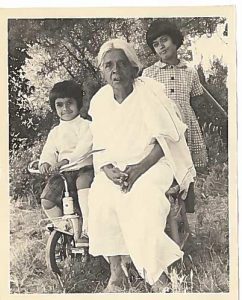

Meera’s granny with Meera’s sister (on tricycle) and Meera age 10

My family’s past is shrouded in legend, myth and history. That’s because my lineage comes from the ancient matrilineal tradition, once prevalent in the southern state of Kerala in India. Now, it is a fading memory, barely remembered.

The origin of this venerable tradition is the stuff of bed-time stories. Every evening after our nightly bath, my sister and I would settle in for a story. Our granny was a natural-born storyteller and each of her stories started with the timeless words, “Long ago when your great-great-grandmother’s grandmother was just a baby….”

This particular tale was a familiar favorite because it was all about our family, a version of a child’s “when you were born” story. Usually her stories were morality tales, centering on our misdeeds of the day so my sister and I usually ignored the parable and concentrated on the story.

“Parasurama was a legendary warrior and hero and was responsible for bringing the Ekkanaths into this world,” my granny began. “It is said that he never traveled without his heavy and sharp battle-axe and he used it to create Kerala, our homeland.

“Parasurama hurled his axe and claimed all the land in between as his own and then he summoned gods, heavenly minstrels and demon women to populate this new land. Soon our first ancestors were born. We are descended from the celestial nymphs and local Brahmin overlords.”

At this point, she would turn a stern eye on us, “That’s why you two can’t go around climbing fruit trees like wild monkeys.”

My granny grew up in our ancestral mansion or “tarawad.” She lived here with her mother, sister and numerous uncles, aunts and cousins. The oldest male relative, usually an uncle, was the head of the household and was called “karnavan.”

Granny left the safety of the “tarawad” to live with her son, my uncle, and her niece, my mother. But she always stayed connected with her family and one day she hoped to become the female head of the household or “tharavattillamma.” She eventually inherited the title as the oldest living female of our house but it was long after she had left for America.

All my life, granny wore the white robes of a widow and we all assumed she had lost her husband early in her married life. It wasn’t until much later; we would learn that her marriage may have been just a simple ceremony called “sambandham” or relationship, not an actual binding marriage contract. In this ceremony, the groom hands over a piece of cloth to the bride before a lit oil lamp and the couple were declared “married.”

This custom was a result of an age-old tradition when the males of the family went off to attend military academies and then served as warriors. The warriors had no time to marry and settle down and their only recreation was these short visits with women living in a “tarawad.” The women were left to raise the offspring. The uncomplicated “sambandham” ceremony allowed the women to live in their own “tarawad” and even find other men as partners. This way of life, including the matriarchy, came to an end when men left the “tarawad” for education and jobs. If you want to read more about this topic, pick up a copy of The Ivory Throne by Manu Pillai.

Extended family photo taken during Meera’s aunt Devi’s coming-out party (her first period which was celebrated by the entire village)

My family, the Ekkanaths, are scattered far and wide and the family home in Kerala is a now plot of overgrown weeds, populated with wildlife and an occasional cobra. Since lineage is traced through the female line, my sons cannot carry on this tradition.

Matriarchy is my family’s intangible legacy, but its traditions run deep in our blood. We may not be part of an active matriarchy but such a long-lasting tradition has left an imprint on all our psyches. It is still evident in subtle ways if you know where to look for it. I see it in my niece’s independence, in my sister’s determination and in the hard work ethic of another niece.

Each day, consciously or unconsciously, we follow in the footsteps of our female ancestors. As long as there are strong Ekkanath (and other) women, working, persisting and pursuing personal empowerment, the matriarchy is still alive and is more than just a bed-time story.

—

Meera Ekkanath Klein is the author of two novels and lives in California. Check out her website: http://meeraklein.com

SEEING CEREMONY

This feel-good sequel to the award-winning My Mother’s Kitchen is all about family, good food, love and finding the way back home. Since the death of her husband three years ago, Meena’s mother has wanted to see her oldest daughter married and so she organizes Meena’s “seeing ceremony,” a ritual associated with arranged marriages. However, eighteen-year-old Meena is not ready to be married and wants to leave her hilltop home in Mahagiri, south India, and attend college in California.

This feel-good sequel to the award-winning My Mother’s Kitchen is all about family, good food, love and finding the way back home. Since the death of her husband three years ago, Meena’s mother has wanted to see her oldest daughter married and so she organizes Meena’s “seeing ceremony,” a ritual associated with arranged marriages. However, eighteen-year-old Meena is not ready to be married and wants to leave her hilltop home in Mahagiri, south India, and attend college in California.

The ceremony is a disaster. Her four years in America soon comes to an end and Meena is eager to return home and share her newly-acquired knowledge of agriculture and tea production with her family. On her journey back to India, Meena meets handsome businessman Raj Kumar with whom she has an instant connection. They end up talking for hours in the airport lounge. When they part at the departure gate, Meena doesn’t think she’ll ever see Raj again. Back in Mahagiri, her mother faces a threat to her home and livelihood. Meena could avert this disaster by agreeing to an arranged marriage. Will Meena have to go through yet another “seeing ceremony?”

Category: On Writing