And Then, Two More: Donna Levin

I wrote a book called Get That Novel Started, some years ago, for Writer’s Digest Books. I had only been a writing instructor for a few years, and sensed that it was soon for me to write a book about craft, but they offered me a book contract, and how often do you turn that down? Answer: Not blooming often.

I wrote a book called Get That Novel Started, some years ago, for Writer’s Digest Books. I had only been a writing instructor for a few years, and sensed that it was soon for me to write a book about craft, but they offered me a book contract, and how often do you turn that down? Answer: Not blooming often.

So I wrote it, and I stand by most of it, but if I had a chance to do another draft, I’d make some changes. Which, as we’ll see, only confirms what I have to say here.

In that book I formulated Levin’s Rule of Rewriting: “Do as many drafts as you can without setting yourself on fire. Then one more.”

Four years later, I wrote another book for Writer’s Digest, Get That Novel Written. In that second book on craft, having had a little more experience, I acknowledged my first adage and said, “I was wrong. It’s two more.”

Students (or audience members, if I’m giving a talk) don’t like to hear this. And it’s not always true, any more than anything else about writing fiction is always true. This leads me to the necessary disclaimer: everything in this piece is, of necessity, an oversimplification.

However many drafts you do, though, it is in the willingness to return to a manuscript, to reassess, often to gut, sometimes to overhaul, then to dig deeper, and finally, to polish, that the women get separated from the girls.

#

Has this ever happened to you?

You finished your novel! You did several drafts, probably at least four. But you know that you need to ask someone to read this, cough-cough, final draft before you start shopping it.

So you show it to a qualified person. What makes a qualified person is an essay unto itself, but with rare exceptions, it is not your partner, your sister, or your best friend. It may be someone who has become a friend, because you met in a writing group, but it should be someone who has experience not only with writing fiction, but with critiquing. You may have to pay this person, and good developmental editors can be expensive. But that’s yet another essay, so for now, let’s stipulate that you have found someone whose judgment you trust.

A few weeks pass. The editor has read your manuscript. Now comes the dreaded moment when you two will meet, and you will hear their feedback. You’re nervous, but part of you fully expects to hear, “This is amazing! I know an agent who’s looking for something just like this!”

Instead they say: “I loved Katelyn. But she needs a bigger problem to overcome. And the murder in chapter ten should be in chapter one.” The next few comments resemble a distant car alarm, as you admit to yourself, “Actually, all I wanted to know was whether to cut the flashback in chapter two.”

It’s a mental process not unlike the one I go through when I see a puddle on the floor, and try to convince myself that I spilled my vitamin water, rather confront the truth: that it is yet another “accident” by my cat, Chardonnay.

You don’t want to overhaul the darn book! Think of the hours, days, weeks, quite likely months involved! Because if you shuffle events around, then you face the Rubik’s cube problem: You line up all the orange squares on one side, but in order get the white squares in their place, you have to shift the orange squares around.

In other words, you can’t cut and paste the murder scene into the earlier chapter. You haven’t given us the necessary background. The characters are in different places in their lives. Orange. White. Orange. White.

A former student once asked me to read her manuscript. It was a competent, that is to say, coherent novel: adequate prose, a comprehensible plot, and characters distinguishable from one another. But, as she categorized it as a suspense novel, it particularly needed improvement in the plot and pace department, which I described to her in my feedback. I was surprised when she returned with a so-called rewrite a week later. She used the track changes feature. Track changes? Track changes is for copyediting. Maybe line editing. Hats off to this valuable feature, impossible to imagine a few decades ago, but by definition, when using it, one can’t see beyond what’s already on the page. What this author needed to do was not just to revise, but to re-envision parts, possibly large parts, of the manuscript.

Push your shoulders back, wiggle your fingers, place them on the keys. Go.

#

That was a tough one. But it’s really finished now, right?

You want confirmation of that, so you go back to the same editor, or you move onto another. That decision relies on too many variables for me to say more than “it depends.”

Either way, though, the editor, the same or the new one, has more input. Not another overhaul; you’re beyond that now, but there’s still more to do.

And you do it. You save the document as a new draft, or under a new title—whatever floats your boat. But you go back and you rewrite, and you change, and you dig deeper. You find new insights, write sharper prose, develop even more complexity in the characters.

You don’t try to please everyone, because that can’t be done. You don’t incorporate every suggestion you ever heard, just the ones that resonate with you.

This is how writers get better: they listen open-mindedly to feedback; they go back and rewrite. Writing may be solitary, but almost no one grows as a writer without input from others.

And one day, you are finished. You know that you’ve taken this book as far as it can go.

It was as many drafts as you could stand, and at least two more. In the end, though, you created something that you can be proud of for the rest of your life.

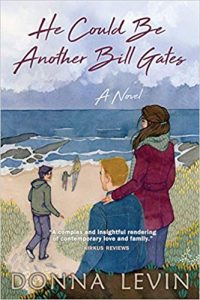

Donna Levin’s most recent novel is He Could Be Another Bill Gates.

—

Donna Levin’s latest novel is He Could Be Another Bill Gates. She’s the author of three previously published novels (Extraordinary Means, California Street, There’s More Than One Way Home), as well as two books on the craft of writing, Get That Novel Started and Get That Novel Written, both published by Writer’s Digest Books. Her papers are part of the California State Library Archives. She lives in San Francisco with her family.

Follow her on Twitter @DonnaLevinWrite

About He Could Be Another Bill Gates:

Anna Kagen had her heart broken five years ago–so badly that she can’t imagine ever having another man in her life. Her ex-husband, Alex, would like her to stay single: that would ensure that he has control of their children, Jack, a 16-year-old on the autism spectrum, and five-year- old Marissa, whose “giftedness” might be wishful thinking on his part, since he needs someone to achieve his own unfulfilled ambitions.

Anna Kagen had her heart broken five years ago–so badly that she can’t imagine ever having another man in her life. Her ex-husband, Alex, would like her to stay single: that would ensure that he has control of their children, Jack, a 16-year-old on the autism spectrum, and five-year- old Marissa, whose “giftedness” might be wishful thinking on his part, since he needs someone to achieve his own unfulfilled ambitions.

As for Jack, he’s ready to open his heart: to the lissome redhead and high school queen bee, Ashleigh. And she’s taking an interest in him! When Anna reconnects with Jason, a man from her past who was once kind to her and who has a special needs son of his own, they seem destined to become a new family. But not if their ex- spouses have anything to say about it….

“Levin’s latest novel will appeal to any parent who has felt stuck between a rock and a hard place. Refreshingly, she doesn’t shy away from the alternately frustrating and triumphant realities of parenting an autistic child. Fans of Rebecca L. Brown and Mark Haddon will appreciate Levin’s tender and realistic portrait of a nontraditional yet immediately recognizable family.” –Booklist

“[A] complex and insightful rendering of contemporary love and family…Jack’s teenage point of view is striking for the glimpse it provides into Asperger’s.” –KirkusReviews

“Being a good parent is always a challenge. Add a particularly challenging child, acknowledge the daily-ness of the work, add wit, compassion, and imagination, and you have He Could Be Another Bill Gates. Levin’s story is compelling and her voice authentic. The result is simultaneously hopeful and sobering.”–Karen Joy Fowler, winner of the PEN/Faulkner award and bestselling author of The Jane Austen Book Club

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips