Being Silenced and Breaking Free

As a memoir coach, I have come to realize that my therapy background, as a family and child therapist for nearly forty years, is something I draw on over and over again when I work with memoirists. Over the years I’ve learned a great deal about human passions, suffering, and courage from people I see in my practice who are carrying traumas from their childhoods and young lives.

As a memoir coach, I have come to realize that my therapy background, as a family and child therapist for nearly forty years, is something I draw on over and over again when I work with memoirists. Over the years I’ve learned a great deal about human passions, suffering, and courage from people I see in my practice who are carrying traumas from their childhoods and young lives.

I’ve learned from victims of abuse, from families struggling to become whole again, and from people who want to create a better life. I’ve learned about the many ways that people are resilient, and about the desire to heal and find a better balance that allows the wounds of the past to fade in intensity.

All of these experiences have helped me to hold the stories of the writers I support. To help them find the words to get the story out into the open so they can create a new relationship with it.

When I first started to write my own memoir, twenty years ago, I started it as fiction. My mother was still alive then, still erasing me by denying I was her daughter (the story told in my memoir, Don’t Call Me Mother, titled for my struggle with her). Having used writing as a survival tool for many years, I could give myself permission to write in my journal, but writing essays or personal narratives that others would know to be true brought so much shame I would feel sick. It was so bad that I would imagine that people reading my work would get sick too! That also made me feel broken and disgusting—and it was a vicious circle.

But I kept writing. I found that each time I wrote and shared my writing, no matter how anxious and shaking and tortured it felt, the feedback I got—from colleagues and fellow students in my MFA program—was measured. They simply read it, or even liked it, and no one got sick or pointed fingers or jeered. It took many of these experiences of sharing and not being rejected for my writing to help me heal my shame. And of course putting into words my story was part of the healing too.

The people who do research on writing as healing, like Dr. James Pennebaker, one of my heroes, say that writing creates a new perspective. We are writing from now, as a witness to the child or young person we once were. We therefore offer that child our adult self now who has a perspective on the story. We offer compassion.

Most writers I work with struggle with breaking silences and healing abuse, and they too find it hard to put words to their experiences. It’s scary, not only to write these stories, but to share them, even with people they trust. The writers I work with have experienced the darker side of human nature and feel marked and different from “regular” people. It’s tough to strive to live a “normal” life when you have been frightened, hurt, or humiliated—wounds that cut deep.

As an adult, you can think and hope that the past is the past and try to simply live in the present, but sometimes the past shows up in the present, clearly and in color. As William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is not dead, it’s not even past.” There’s a widespread epidemic we face as a society around depression and other mental illness, and while this suggests its prevalence, society still harshly judges those who need help, and those who are trying to heal the past.

For those of us struggling to heal from the past, silence was how we protected ourselves; sometimes it protected others as well. We need to seek self-forgiveness, and to understand that our behavior was based on the need to survive. Abused people carry guilt and shame—for what was done to them. This is strange but true. As writers, we can learn about our own power, the power to shape our narrative, to create our story. Writing helps to sort through the confusing layers from the past and weave our stories in a way that makes sense and presents our truths. We do not fictionalize the story, we shape it. We choose the words, style, themes, and arc.

It’s understood now more than ever that trauma affects the brain, how we think and process emotion. At the same time we know, from decades of study about the brain, that we can change our brains—and we can do this by using the simple tool that is writing. We can heal the deep reaches of trauma in our minds by putting together stories. By becoming the narrators of our lives.

I tell the writers I work with:

- You have the power to name what needs to be named. To write your truth. To shape your story as you experienced it. You are the author of your story, truly. You are the expert on your story—what happened, who was there, and who did what to whom. Your story is your testimony. You are the authority of your own story. Get started now and write. Start with a significant moment that has defined your life.

- Write a story you have never written before. Let out the secrets and hidden truths.

- Write about how you were silenced and what you have done to break that silence.

- List five reasons you feel your story is unique and how it can help others.

Each story is a stepping stone to freedom from the past. When you put into words what you have not said before, the truths that you have hidden even from yourself, freedom opens up to you. For me, this happened recently when I brought my latest memoir to my hometown and gave a reading. There I stood, once a prisoner of shame, with my story in my hand. The old fears and worries about sharing what happened in my childhood with a mentally ill mother and grandmother, with being the ugly duckling as a child and rejected, fell away. In sharing what had happened and voicing it aloud, I was free!

—

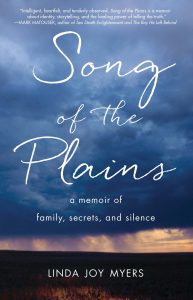

Linda Joy Myers, author of the award winning Song of the Plains where she seeks to explore the themes of healing, secrets, and silence. Her first memoir Don’t Call Me Mother is about healing three generations of mother-daughter abandonment. Linda Joy is the president and founder of the National Association of Memoir writers, and has been a therapist for the last forty years. She enjoys coaching writers who are capturing the stories that have stayed too long in silence. Linda is the author of The Power of Memoir and Journey of Memoir, and co-author of Breaking Ground on your Memoir and The Magic of Memoir.

Please visit www.memoriesandmemoirs.com; www.namw.org. www.lindajoymyersauthor.com

About SONGS OF THE PLAINS

Ever since she was a child, Linda Joy Myers felt the power of the past. As the third daughter in her family to be abandoned or estranged by a mother, she observed the consequences of that heritage on the women she loved as well as herself. But thanks to the stories told to her by her great-grandmother, Myers received a gift that proved crucial in her life: the idea that everyone is a walking storybook, and that we all have within us the key to a deeper understanding of life—the secret stories that make themselves known even without words.

Ever since she was a child, Linda Joy Myers felt the power of the past. As the third daughter in her family to be abandoned or estranged by a mother, she observed the consequences of that heritage on the women she loved as well as herself. But thanks to the stories told to her by her great-grandmother, Myers received a gift that proved crucial in her life: the idea that everyone is a walking storybook, and that we all have within us the key to a deeper understanding of life—the secret stories that make themselves known even without words.

Song of the Plains is a weaving of family history that starts in the Oklahoma plains and spans over forty years as Myers combs through dusty archives, family stories, and genealogy online. She discovers the secrets that help to explain the fractures in her family, and the ways in which her mother and grandmother found a way not only to survive the great challenges of their eras, but to thrive despite mental illness and abuse. She discovers how decisions made long ago broke her family apart—and she makes it her life’s work to change her family story from one of abuse and loss to one of finding and creating a new story of hope, forgiveness, healing, and love.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Wonderful post, Linda. I’m sure your mental health training and experience is invaluable to your memoirist clients. I often want to hand my therapist my manuscript and say, “Here- help figure me out.” And writing does change your perspective. Two years ago, when I picked up with the memoir I started 20 years before and then dropped a few years later, my perspective was that I was a bad mom. I was not the mom my young son needed through his rumble with a brain tumor. He needed someone better. Now that I’ve returned to the writing, I realize I was an awesome mom. Flawed, yes, but fiercely and persistently loving, no matter how hard it got.