First Person Novels – Love or Hate?

Alice Jolly looks at the risks and rewards of novels written in extraordinary first person voices.

I know people who never read a novel written in the first person. I do see their point. First person novels can be like finding yourself wedged on a train next to someone who is chatty, over sharing, mendacious and has bad breath. And there’s no getting rid of them even though you’ve positioned your mobile phone two inches from your face.

I know people who never read a novel written in the first person. I do see their point. First person novels can be like finding yourself wedged on a train next to someone who is chatty, over sharing, mendacious and has bad breath. And there’s no getting rid of them even though you’ve positioned your mobile phone two inches from your face.

Too often you suspect that the ‘I’ of the book is actually the author themselves and you want to say, ‘Look, as a novelist, you do need to make stuff up – or stick to memoir.’ Because memoir, oddly, does not raise quite the same issues. The writer of a memoir is a real person so we cut them some slack.

The first person characters in novels are fair game. The ticker-tape of someone else’s head can be unpleasant. All that self absorbed whingeing and me-me-me. We long for the case for the prosecution to be heard, for another viewpoint which will give some wider perspective on events. We thirst for a window to be opened in the text. The first person is almost by definition an anti-epic approach.

Claustrophobia is far from the only problem. There are also significant textual challenges. The word ‘I’ stretches across the text, like a line of telegraph poles looping across both the aural and visual landscape, creating an insistent rhythm which drags on the ear and the eye.

But the reality is that all of this can be argued the other way. It all depends on the particular voice and the skill of the writer. Voice is the muscle of the soul and, when it works, the power of a specific voice speaking direct to camera is unparalleled. And it isn’t just character which suddenly arises fully formed from speech. Place, class, era, age can often seamlessly be explained just by the sound of a voice. The essence of the novel can be created in specific turns of phrase, considered choice of vocabulary, rhythms of speech. Direct address for a novelist is an amazing short cut, potentially saving on many pages of description and explanation.

First person can also bring a wonderful urgency to the telling. Like the Ancient Mariner, the first person narrator waylays us on our way to the wedding ceremony and will not let go until we’ve heard the whole damned story. We may not want to listen but their need draws us in.

But still, first person remains a boom-bust strategy. The more eccentric the first person voice, the bigger the risk. Some people will find that they hate the voice, or that it is simply too difficult to read, and put the book down after the first two pages.

I did that with Train Spotting. I nearly did that with Last Exit to Brooklyn and was glad that I didn’t. By the time I’d finished although I’d been bored, shocked, frustrated and depressed – the book immediately took its place on my top ten all-time favourite books.

The first person novel also opens up the possibility to create an unreliable narrator. Whether deliberate liar or self deceiver – these narrators always make uncomfortable book-fellows. We love these books because they flatter us. We know that while the ‘I’ of the character is saying one thing, the ‘I’ of the writer says the opposite and that makes us feel clever. Also (as in Lolita) we want to get out but we want to stay in – and it is precisely that painful push and pull which can make such novels horribly disturbing.

First person also creates the possibility to ‘cast the reader.’ The writer can turn the reader into a chosen confidant, a judge, or a person we hope to draw in, confuse or trick. In doing so the writer makes the reader complicit in the book and in what our character says. Again the effect can be pleasurable or disturbing – depending on whether the reader agrees to take on that given role or fight against it.

There are always delicate judgements to be made about how far to push the reader. When does strange become too strange? Finding that balance may be partially dependent on plot and length. We might listen to a difficult voice for 200 pages but not for another hundred (Eimear McBride – A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing is brilliant but does not need to one page longer). We may be prepared to listen for longer if the plot is strong (Peter Carey – The Secret History of the Kelly Gang).

Every time I set out to write a novel I tell myself that I’m not allowed to write it in the first person. But sometimes you have to bow to the logic of the characters and the overall needs of the book. Finally the playwright in me is always fascinated by voice. So I’ll probably keep on spinning the roulette wheel as long as I’m writing. For all the bad-breath people who corner you on the train, you might also meet a life-long love.

—

Alice Jolly is a novelist and playwright. She has won the Pen Ackerley Prize for memoir and also the V.S.Pritchett Prize awarded by the Royal Society of Literature.

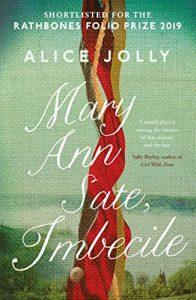

She teaches creative writing on the Masters Degree at Oxford University. Her fourth novel ‘Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile’ was a Walter Scott Prize recommended novel for 2109, was on the longlist for the Ondaatje Prize 2019 and was runner up for the Rathbones Folio Prize 2019.

Follow her on Twitter @JollyAlice

MARY ANN SATE, IMBECILE

SHORTLISTED FOR THE RATHBONES FOLIO PRIZE 2019

SHORTLISTED FOR THE RATHBONES FOLIO PRIZE 2019

‘A lyrical tour de force’ Guardian

Longlisted for the RSL Ondaatje Prize 2019

2019 Walter Scott Prize Academy recommendation

If you tell a story oft enough

So it become true

As the nineteenth century draws towards a close, Mary Ann Sate, an elderly maidservant, sets out to write her truth.

She writes of the Valleys that she loves, of the poisonous rivalry between her employer’s two sons and of a terrible choice which tore her world apart.

Her haunting and poignant story brings to life a period of strife and rapid social change, and evokes the struggles of those who lived in poverty and have been forgotten by history.

In this fictional found memoir, novelist Alice Jolly uses the astonishing voice of Mary Ann to recreate history as seen from a woman’s perspective and to give joyful, poetic voice to the silenced women of the past.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

I can cope with first person – as long as it’s done well. It’s present tense first person, when the ‘I’ persona becomes even more insistent, that I find irritating.