From a Haunted Graveyard to a Historical Novel

Nancy Hayes Kilgore

Nancy Hayes Kilgore

My daughter looks puzzled. “I thought we came to see a prison,” she says. The soft yellow stone and harmonious planes of the Greyfriars Kirk, surrounded by a shady park and weathered gravestones, with no prison in sight, feels like a serene oasis in the middle of Edinburgh. But we have come to see the Covenanters’ Prison where some of our ancestors are buried.

I remember as a teenager sitting in the living room of my grandparents’ Victorian house in Pittsburgh. Perched on the horsehair sofa beside the coal stove, as my grandfather recited names, dates, and facts from his family history book, I was utterly bored. Especially with that long line of Presbyterian ministers. Oh, please. I’d grown up with Presbyterian ministers, men in long black robes droning on and on from the pulpit.

But something happened when I became an adult that, back then, gazing out the tall Victorian windows, I never could have imagined. I became a Presbyterian minister myself.

Now I was interested in these ancestors. I dug out grandfather’s book. Flipping through the pages to those who came from Scotland, I saw a new word: Covenanters. A few hundred years ago, some of these Presbyterian ministers were “Covenanters.” What did that mean?

The only visible remnant I could find of these people was the Covenanters Prison, at Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh. During the Scottish Reformation, these people had signed a covenant pledging to resist English Episcopacy and its notion of divine right of kings. With this, the Covenanters thrust themselves into years of bloodshed and battle against both the English and the Catholic royalists. Eventually, they were defeated at the battle of Bothwell Bridge in 1679, captured, and taken to a field near Greyfriars Kirk. Over that one winter, they were kept in this outside prison, tortured, starved, and died. The prison became a graveyard, and the Covenanters were buried here.

We look around the shady churchyard. The graceful church is inviting, and other tourists are going into it; but we have come to see the prison graveyard where some of our ancestors are buried.

Finally, at the far end of the yard beneath the trees, we spy a group of people standing in front of an iron-barred gate.

The gate guards an opening in a high stone wall secured by an enormous black padlock. The people are peering through the bars.

“That must be it,” I say. But why would it be locked?

A small sign on the gate reads “Covenanters Prison.”

We squeeze in and look through the bars into an alley lined by crumbling stone-walled cells and corroded gravestones. It must be locked, I think, because the stone is falling down.

At the end of the alley, like a menacing throne, looms a mausoleum. I can’t read any names on the gravestones, but here is where my ancestors were tortured, starved, left to die, and then buried.

Suddenly a wave shoots through my body, like a chill, but much stronger and deeper. I step back. Cold and black, like a plunge into hell, there is no name for this kind of dread. Like a visitation, something I’ve never experienced.

Is there something in my genes that remembers this place?

My daughter beside me is calmly reading the plaque.

I turn to the man standing next to me. “Pretty creepy,” I say, an understatement. The man spins around. “Don’t you know about the ghost?”

“Ghost?”

“This place is haunted. People have been hit, scratched, and knocked down in there. That’s why the city has locked the gate.”

The mausoleum at the head of the alley, he explains, is the tomb of George Mackenzie, the judge and warden who presided over the prison. This man’s cruelty and lack of mercy earned him the moniker “Bloody Mackenzie.’” Ironically, he, too, was buried here, his tomb overlooking the graves of the people he had tortured and killed.

In the 1990s, a homeless man went into the mausoleum and tried to break into the casket. This supposedly unleashed Mackenzie’s evil spirit, and since then visitors have experienced all sorts of invisible attacks.

I am skeptical about ghosts, but I can’t deny the feeling I just had. And apparently the city of Edinburgh, in spite of its history of enlightened thought and advances in science and philosophy, has officially validated, by locking the gat, an evil supernatural presence here.

“They do let people in on the tours,” the man says. “Haunted Edinburgh tours.” “No thanks, I’ll pass on that one,” I said.

Later, I discover that the family of Hay (my birth name, Hayes, is an Americanization of Hay) lived in the region of Moray, a Covenanter area where many of the witch trials in Scotland occurred.

Now I am confronted with the fact that my ancestors, the Covenanters, who were tortured and killed at Greyfriars Kirk, had themselves tortured and killed women they accused as witches. And on the estate of a laird named John Hay occurred one of the most famous witch trials in Scottish history – that of Isobel Gowdie.

Before I became a minister and developed some empathy for my Presbyterian ancestors, I had delved into other kinds of spirituality, including the Wiccan philosophy of Starhawk. I loved the earth-based spirituality and healing that she described, and it was still a part of my worldview.

Here were two opposing theologies, two sides of my own history, that collided in the 17th century. Here was a story. It was about Isobel Gowdie, a cunning woman from the traditional world of visionaries, shamans, and psychics, and the Christian Reformation Scotland that condemned her.

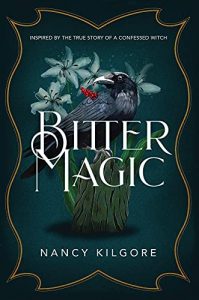

Fifteen years after that visit to the Covenanters Prison, the novel, Bitter Magic, was born.

—

Nancy Hayes Kilgore is the author of three novels, BITTER MAGIC (Sunbury Press, 2021,) Wild Mountain (Green Writers Press, 2017,) and Sea Level (RCWMS, 2011). She is recipient of the Vermont Writers Prize, a ForeWord Reviews Book of the Year, and a Pushcart Prize nomination.

Find out more about Nancy on her website: https://www.nancykilgore.com/

BITTER MAGIC, Nancy Killgore

Bitter Magic, inspired by the true story of Isobel Gowdie and her witchcraft confession, reveals a little-known corner of history—the lives of both pagan and Protestant women in the Scottish Reformation of the 1600s as witch trials and executions threatened their lives, values, and beliefs.

The story is told by Isobel herself and also by Margaret Hay, a fictionalized seventeen-year-old noble woman. When Margaret stumbles across Isobel one day, it seems as though Isobel is commanding the dolphins in the ocean to dance. Margaret is enchanted. She becomes interested in Isobel’s magic, in fairies, and in herbal remedies; Isobel freely shares her knowledge. While Margaret worries that being around Isobel could be dangerous, she also respects Isobel’s medical successes and comes to believe that acknowledging the efficacy of herbal remedies or believing in fairies does not challenge her Christianity.

But Isobel believes in more than cheery fairies and herbal medicine. She has dark wishes as well, unknown to most people. Isobel seeks vengeance against the local lord who executed her mother for witchcraft. More important, Isobel’s trance experiences (or are they dreams?) lead her to confess to a wide range of sins, including consorting with the devil. Then, during her trial, Isobel names thirteen others, calling them all witches. To her great shock, Margaret hears her own name. Can her tutor, a Christian mystic named Katharine, save them?

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Wow! What a story. I am deep into researching my family’s genealogy just for posterity for my family’s edification. All of my parents’ generation have passed on and all but one of my siblings who is much younger and half of my cousins have passed on as well.I don’t expect to discover witchcraft or the kind of persecution your ancestors experienced. I have Irish relatives who bitterly remember the British history of outlawing the Catholic religion and an great-uncle who fled Ireland because the authorities suspected he was in the IRA, which he was.

I love how you’ve woven sad, bitter family history into what appears to be a compelling work of fiction. I will check it out.