From Novel to Memoir

I have always wanted to write novels. My very first novel was published by a company who specialised in short novels written for the older end of the reading market ie love but no sex, and were available only through libraries. I was delighted. My career had taken off.

I have always wanted to write novels. My very first novel was published by a company who specialised in short novels written for the older end of the reading market ie love but no sex, and were available only through libraries. I was delighted. My career had taken off.

Not so, as we writers know. I produced several more novels which no one wanted, although I did get encouraging letter from publishers.

I was keen to write about an incident which happened to me in the mid-1960s, when I was a teenager. Today the subject would be classed as life writing. It was the story of the breakdown of the relationship between me and my mother, over about two and half years. The incident hung on the fact that I was a pregnant school girl. So yes, a big deal.

I’d started to write this history as a novel while my mother was still alive. She’d never read it. She wasn’t the book buying kind. I produced several versions, all rejected, put it away to work on short stories and a new novel. My mother died, releasing me from that guilt which told me I shouldn’t be writing about this painful incident at all.

I submitted the final version of the novel to 48 agents. One agent was kind enough to reply, ‘This struggles not to be a memoir.’ I had both a reprieve from my conscience and permission to write my story while solving that eternal problem ‘1st or 3rd person narrator?’ I changed the voice to mine.

The obvious difference between a novel and a memoir is that novels are ‘made up’; the clue about the latter is that the words come from memory – with more personal emotion, plus research to reinforce the situation.

I am blessed with a strong memory for detail. I can restore smells, sounds, the atmosphere of a room, clear moments of laughter and of tears. I took one of my drafts, the most straight forward version, written in first person. I laid out all the chapters on the floor, assessed them, tore some up, realised they fell into two clear parts of the story, and began to re-write and re-construct.

The writing was sheer joy. I could include all the memories, the incidents, the quarrels, the times when things were at their worst, the stories of others involved as the story progressed and the emotional and, almost shocking, climax. I bought non-fiction books on the subject of unmarried mothers and found interesting and useful information and statistics. How many girls at that time became unmarried mothers? What was the reaction of society to their dilemma? What happened to the babies? One aspect was clear in my mind. I wanted to create a completely different picture from the terrible one coming out of Ireland about the treatment of those abused and un-cared-for young women.

But I also wanted my narrative to carry the readers forward, to include plot points to make them want to read on, and, finally, not only to show the stress between myself and my mother but to include the forgiveness offered and taken on both sides and the redemption. I had to give my mother a fair ‘listening to’. In other words, my memoir had to be a construct.

I wrote a new beginning, one to stimulate my readers’ curiosity. Later in the memoir, I had to persuade readers I’d done the right thing in my change of heart about marrying the father of my child. I moved the vital chapter which conveyed this from early in the narrative to form the turning point in the memoir, at the half-way point, from the negative to the positive. I wanted to convey the happiness I experienced in the mother-and-baby home while consistently introducing new questions to be answered, new problems to be solved.

I wrote a chapter documenting my mother’s story, giving reasons why her upbringing formed her nature and thus why her treatment of me appeared so hard-hearted but also making it clear that we made our peace. This was essential to completing the memoir.

And then I had a glorious piece of luck. I was listening to one of those phone-in programmes about adoption. A man rang in to say he hated his mother for giving him away and he would never forgive her. Here was my audience. I had to tell this man and others like him, what it was like, how impossible it was for youngsters like me, in a situation where we were totally helpless. I had my incentive to get this book right and get it out there. The book has now been published. I can move onto other writing.

There is nothing wrong with wanting to write down your memories. We remember our childhood days and the stories we listened to beginning, ‘Once Upon a Time…’ And we long to do the same for our children and grandchildren. We want to tell them the story of our lives. Or do we? Isn’t it really that we want to tell them stories from our lives?

Because that is what memoir is. A story, one incident, from our life. The time scale can be long or short; the geography of the story local or worldwide; the characters few or many. It should be one tale told, with a beginning, middle and end but not necessarily in that order.

I have received many heartening messages from readers, and have had good reviews. The book is selling slowly but it is selling. I am receiving those writerly things ‘royalties.’ I am enjoying talking to book groups. What the book is not doing, sadly, is reaching those people at the end of the story, those given up in adoption. People can’t be forced to buy and read what they don’t want to. But I have no regrets.

If you want to write your story, forget pretending, abandon gilding the truth, put all the words on paper, truthfully, no embellishment necessary, and you will achieve gold.

—

Jane writes long and short fiction, with a novel published by Robert Hale, stories short-listed by Comma Press and The Liar’s League and published by indie publishers. Her dark tale The Way to a Man’s Heart won an international writing prize and is published in an anthology by Alma Press. An excerpt from an early draft of this memoir was short-listed for the Fish Short Memoir Prize and a short story borne out of the memoir is published at http://mironline.org/jane-hayward.

Jane has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. She lives in London.

You can find her on twitter @jane_hayward, on Facebook and on Radio Gorgeous at https://player.fm/…/radio-gorgeous/sent-in-shame-to-a-mother-and-baby-home.

Or at https://audioboom.com/…/7205616

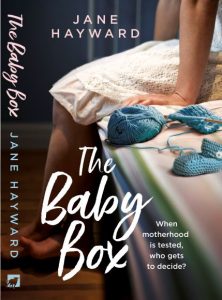

Jane Hayward’s memoir, The Baby Box, is available to order through bookshops and from Amazon.

She is working on a collection of stories, The Way to Dusty Death and a novel set in the 1950s. Jane is seeking representation in the USA.

THE BABY BOX

It is December 1964. Jane’s mother is preparing for Christmas while Jane is refusing to take a do-it-yourself abortion pill from her school chum Rita. Persuading the father of the child, Nick, to be with her on Christmas Eve, Jane announces to her parents she is pregnant. Her mother wishes she’d dug the baby out with knitting needles. Jane’s father threatens Nick, throwing him out of the house. Nick leaves without saying `Good-bye’.

It is December 1964. Jane’s mother is preparing for Christmas while Jane is refusing to take a do-it-yourself abortion pill from her school chum Rita. Persuading the father of the child, Nick, to be with her on Christmas Eve, Jane announces to her parents she is pregnant. Her mother wishes she’d dug the baby out with knitting needles. Jane’s father threatens Nick, throwing him out of the house. Nick leaves without saying `Good-bye’.

Jane’s summer of love has presented her with an appalling dilemma: to marry a man she now knows is a coward or to face the future as an outcast with a child to care for. It is vital for her respectable mother to keep her daughter’s shame secret.

Any love is smothered as she berates Jane for bringing disgrace into the family. Imprisoned in the house, Jane waits in vain for Nick to give her some kind of support, but he cannot even keep a job. While her mother turns to an old friend from the war, Fiona, for comfort, Jane is consigned to the care of a moral welfare officer. Fiona has the answer to Jane’s mother’s predicament. The following spring, Jane is banished to a mother-and-baby home.

Perhaps the first of its kind, The Baby Box is a frank memoir, set in the 1960s, of a pregnant schoolgirl, written in a compelling first person account. The book highlights the prejudices of the day with some distressing, sometimes disturbing, truths. But this is not a misery memoir. Moving into the mother-and-baby home brings tales of the other girls, maintaining an upbeat story. Those who enjoy memoirs, especially those reminiscent of an era, as well as readers who are looking for a true story with depth, will be engrossed in this tale of lies, deceptions and hidden shame, but ending in redemption.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing