In Defense of Head-Hopping

In writing, head hopping is defined as using an omniscient third-person narrator to hop from the head of one character right into another. This is thought to cause confusion for the reader and leave them wondering whose thoughts they’re supposed to follow now.

I understand that the idea of keeping a sharp line between the mind of one character and another is tempting. Many say this is essential, and to blur that line suggests that you don’t know what you’re doing as a writer. Your skill comes into question. It’s best, though, to remember that in good writing, there really aren’t any rules, as long as you’re keeping the reader firmly located in what’s going on.

Anne Leigh Parrish

I do a lot of head-hopping. My reason is simple. I want to promote the idea that all characters have a seat at the table – that they’re all equally valuable, none more than another. I could just use the third person voice to demonstrate this without head-hopping, but I want to further suggest the possibility that people can occupy a shared psychic space, even if they’re not fully aware of it.

I don’t mean that two characters necessarily think the same thoughts at the same time, but if the boundary between them has lessened, and the reader flows from one soul to another, this is ineffably understood. The shared space holds those big life-changing experiences like loss, regret, guilt, and grief. These are what humans being have in common. Also joy, hope, love, and desire.

In my short story, “Where Love Lies,” (Issue 03 of Literary Orphans) an unlikely alliance forms between a woman and a man thirty years her senior. The woman, Dana, has fled an abusive marriage. Her friend, Bruce, is a widower. His late wife committed suicide when a man she’d fallen in love with refused her advances. Bruce understood the falling in love. He suffers from erectile dysfunction (and hasn’t caught up with the wonder drugs around to solve the problem). Bruce realizes he’s fallen in love with Dana. They’re drinking in a bar, and both are wondering if they’ll end up in bed together.

They each think back to their past relationships. Then they enter a shared space. “Dana thought that nothing was her fault. Bruce thought that everything was his fault.” While Dana experiences redemption, and Bruce guilt, they are reflecting on the same thing at the same time, though the specifics aren’t shared, only the inquiry. Dana and Bruce have joined a larger mass of humanity in that moment, and to an extent they have also joined each other, though the joining is short-lived.

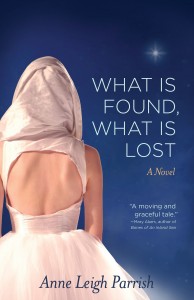

My new novel, What Is Found, What Is Lost, combines head-hopping with a fluid structure, moving through time from present to past and back again. Why the shifting eras? Again, to underscore the concept of commonality, or in this particular case, that there are eternal truths. One that’s key is the tough time mothers and daughters have understanding one another. Whether it’s 1929, 1960, or 2012, this is the case for my female protagonists. And these four generations of women share other traits, too. They’re all stubborn, yet given to wild flights of fancy. Their relationship with men is fraught with tension and disappointment. They’re all lonely. They all struggle with money.

My new novel, What Is Found, What Is Lost, combines head-hopping with a fluid structure, moving through time from present to past and back again. Why the shifting eras? Again, to underscore the concept of commonality, or in this particular case, that there are eternal truths. One that’s key is the tough time mothers and daughters have understanding one another. Whether it’s 1929, 1960, or 2012, this is the case for my female protagonists. And these four generations of women share other traits, too. They’re all stubborn, yet given to wild flights of fancy. Their relationship with men is fraught with tension and disappointment. They’re all lonely. They all struggle with money.

Another theme in the novel which suggests fluidity is religion. Not one, but many, observed, experienced, assessed in a non-judgmental manner that makes it clear where I stand – none is better than another, none has unique access to divine truth. I tend to view religion almost from an anthropological standpoint. There exists a universal human to need to believe in something larger than ourselves, and I invite the reader to glide seamlessly among them, without getting distracted by tenets.

In sum, heading-hopping, layers of history, and an objective, fair approach to religion are my way of saying that what we have in common is far greater than what divides us.

I hope you’ll agree.

—

Anne Leigh Parrish’s debut novel, What Is Found, What Is Lost, came out in October 2014 from She Writes Press. Her second story collection, Our Love Could Light The World (She Writes Press, 2013) was a finalist in both the International Book Awards and the Best Book Awards. Her first collection, All The Roads That Lead From Home (Press 53, 2011) won a silver medal in the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards. She is the fiction editor for the online literary magazine, Eclectica. She lives in Seattle.

What Is Found, What Is Lost: A Novel (She Writes Press, October 2014)

Our Love Could Light The World: Stories (She Writes Press, 2013), Finalist the short story category of the 2014 Next Generation Indie Book Awards; Finalist in both the 2013 International Book Awards and the 2013 Best Books Awards

All The Roads That Lead From Home: Stories (Press 53, 2011), 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards Silver Medal Winner

Website: www.anneleighparrish.com

Twitter: www.twitter.com/AnneLParrish

Facebook: www.facebook.com/AnneLeighParrish

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Um, no, that’s not what omniscient is. I hate to say it, but if you think of it as head hopping, then you probably are head hopping. Head hopping happens when a writer can’t really make up his mind what viewpoint to use, so he wants to tell everyone’s story. The result is UNCONTROLLED POV shifts.

Omniscient viewpoint is actually ONE viewpoint. It’s an all seeing narrator who is visiting all these characters and telling there story – sort of like the storyteller who sits down to tell you a story. Writers have a really hard time understanding what Omni is because they’re trying to frame it from regular third person, so it can look like multiple viewpoints.

In terms of moving from character to character, there’s a shift in the wording. The narrator will go down into the character’s head, then pull out with a few sentences, then shift over to another character. It’s actually hard to do in the learning stage because you really have to make that shift that gets in there. Because Omni is so misunderstood and so much reported is incorrect, you have to go to the source. Find Omni writers. Study them.

Thanks for your post, Anne (and glad to see another She Writes author in this space.)

I’d not heard that term (head-hopping)- and so far haven’t written anything that warrants its use (since my work has been essay and memoir.) But reading your post will make me think as I read others’ works and see how they do it!

Music to my ears. I have struggled to conform to third person POV and now shaken off the shackles. The plots of my thrillers move too far and too fast with too many characters for anything other than omniscient. Let the comeback begin.

Thank you for this! Head hopping has grown from legitimate criticism to an attack on the third person omniscient voice. I can see some uses, like switching from one POV to another for only a few sentences, being called out for good reason, but an entire, recognised, traditionally used narrative voice? No.

I’ve seen a lot of criticism that almost sounds like bird-watching: “Head hopping! I found head hopping! You’re not supposed to do that!” Just a recognition of the structure, with no analysis of the actual text.

Linda,

Thanks so much! I hope you’ll give the novel a look and see if I pulled everything off.

Anne, yours sounds like a fascinating novel. Omniscient is not as common as it once was, and it’s not easy to pull it off. I recently read “Panic in a Suitcase,” which has an omniscient third person narrator. It was so wonderfully done. It sounds to me like you know what you’re doing.