Interview with Maggie Humm

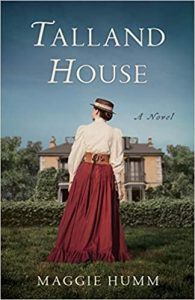

Interview with Maggie Humm, author of Talland House

Interview with Maggie Humm, author of Talland House

Talland House takes Lily Briscoe the artist character from the confines of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Set between 1900 and 1919 in picturesque Cornwall and war-blasted London, the novel tells Lily’s emotional journey in becoming a professional artist: her love-life, mourning her dead mother, as a suffragette, and solving the mystery of Mrs Ramsay’s sudden death. Talland House combines a detective story with romance and history with echoes of the present moment and solves a literary mystery which has puzzled twentieth-century readers. I’m delighted that Talland House was shortlisted for four novel prizes (Impress, Retreat West, Eyelands, Fresher Fiction) and longlisted for two (Lucy Cavendish and Historical Writers Association) https://amzn.to/2UJZ7zF

What was the initial inspiration for your novel?

Virginia Woolf’s wonderful, quasi-autobiographical To the Lighthouse. Woolf recreates her father and mother as Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay. I first read To the Lighthouse as an adolescent after the death of my mother and fell in love with the mother-figure Mrs Ramsay. Later I discovered that Woolf’s mother Julia Stephen was 49 when she died and Virginia 13 – the exact ages of my mother and me when my mother died. There’s something so extraordinarily moving about mothering in To the Lighthouse, but Mrs. Ramsay dies suddenly and in parentheses (apologies to those who haven’t yet read the book!) and I knew I had to write a novel discovering how Mrs. Ramsay dies.

How long have you been working on the book? Did it involve any special research?

Years! After writing and re-writing I took a University of East Anglia/Guardian Diploma in Creative Writing followed by mentoring with The Literary Consultancy.

The research was huge but so enjoyable. As a Woolf scholar (my last three books focus on Woolf and the arts) I’d read all Woolf’s writings and writings by her family and friends. For Talland House I read Cornish newspapers for the times Lily is in St. Ives for weather, incidents, and atmosphere. I loved being in the airy map room at the top of the British Library looking at old photos of St. Ives for housing types and street scenes. I read artists’ memoirs, turn of the twentieth century art journals for a sense of artists’ lives and studios. I read everything on-line about World War I in London and how it felt to be there, for example, when the Germans suddenly switched from Zeppelins to Gotha bombers in 1917. Virginia Woolf herself experienced Gothas in Richmond December 1917. She wrote in her diary: “discussed the raid, which, according to the Star I bought, was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons & 2 were brought down”. I googled about music halls, other leisure pursuits, clothes, transport, and the accurate names of buildings. St. Ives and London became characters in my novel!

How difficult was it to change from academic to fiction writing?

Very difficult! After decades of academic writing, fiction writing seems another country, another world, with its different hierarchies of agents and editors, rules of engagement, and profile “creation” not least on Twitter—all completely new and intimidating to me at seventy-three. Twitter has a campaign to persuade arts and literary prize givers to change their entrance rules from “young” (or using named age ranges), to “emerging” artists and writers. The UK Tate Turner Prize removed their age restriction in 2017.

Very difficult! After decades of academic writing, fiction writing seems another country, another world, with its different hierarchies of agents and editors, rules of engagement, and profile “creation” not least on Twitter—all completely new and intimidating to me at seventy-three. Twitter has a campaign to persuade arts and literary prize givers to change their entrance rules from “young” (or using named age ranges), to “emerging” artists and writers. The UK Tate Turner Prize removed their age restriction in 2017.

In some ways, I often incorporated fictionalised sections into my critical writing. For example, juxtaposing the story of Washoe the female chimpanzee, who learned American sign language, and continually crossed between her natural repertoire and ASL, and feminists in the academy who survive by learning to speak two or more, “languages”.

Yet while similar techniques can feature in both academic and creative writing, most notably the use of transitions, the differences are crucial. Academic writing is, or should be, clear and explicit, clarifying and defending an argument (although mine is, sadly, often associative). Creative writing, on the other hand, is suggestive, with ideas and similarities between events implicit rather than explicit—the old “show” not “tell.” A single image can carry an overriding theme.

What was the most difficult thing about writing your novel?

The most difficult task was keeping the research to a discreet underpinning not, as academics often do, glorifying it in long footnotes. What the research also did, was to bring me much closer than ever before, to a fuller sensation of Woolf’s worlds—the smell and feel of Talland House’s escallonia hedge, an almost bodily sense of the impact of bombs on London’s buildings, streets and inhabitants.

This feeling for history and sensory experiences continues in my creative writing: short stories and a second novel, Rodin’s Mistress, about the tumultuous love affair of the sculptor Auguste Rodin and the painter Gwen John.

Also difficult was that Lily gradually took over my life, my feelings, even my physical characteristics. She’s always early for appointments, she’s an only child herself with a dead mother, and her fingers are the shape of mine. Sometimes I wondered if I existed outside the novel!

Do you have any hints or tips for people who want to start writing?

Research the world you want the reader to share so that you come to know that world as well as your own. Then just start writing. Once you get to 30,000 words, you’ll know you can write a novel.

Find more at http://www.maggiehumm.net/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, Interviews, On Writing