Life By The Books

Photo by Ann Bickel

I’ve been wondering lately if one day I’ll look back on my creative work in terms of the life chapters during which the work was done.

I wrote my first book, a memoir, in my twenties. Part of it I wrote as my master’s thesis, part of it I wrote while teaching. Although I was busy (or thought I was), I could still carve out large chunks of time to work, uninterrupted. On the days when I wasn’t teaching, I could write for hours on end, the word count climbing.

How different the process was with my second book. Although I’d written a book before, this undertaking required a complete revamping of my process and approach. For starters, I was writing a novel: I had to learn how to write fiction, which wasn’t the easy transition I’d naively thought it would be. But equally significant was the fact that I began this book shortly after becoming a mother. Gone were the days of uninterrupted hours and mounting word counts. Gone, too, was the silence that allowed me to think.

My writing, just like my life at the time, became an unending scuttle of trial and error, a sentence-by-sentence, spare minute-by-spare minute piece of work, thrown off by countless interludes of flus and phases. Perhaps not surprisingly, the book has little to do with children.

And yet I’ll remember writing it in a chapter that felt entirely about children. It’s a book written during baby-wearing and night-waking and nursing and weaning, a book of first foods and first steps. And—perhaps this is the one thing I’ll remember most about the actual writing of the book—it was written with endless interruptions.

As disheartening as it was, in the thick of those 1800 days or so of writing, to open a document, write a sentence, and have one of the boys start hollering for me, I wouldn’t change it, not now. Though I can barely believe it, this chapter of my life has ended, and while the sentences of the book remain, the days are gone. The small people who were, in their myriad ways inspiring those sentences, have evolved already. No more Baby Bjorn carrier, no more spit-up.

If I allow myself to be optimistic I’ll dream there will be more books. The one I’m writing now will be the book of Legos and Tonka trucks, fireflies in Mason jars, bike-wrecked knees, loose teeth. The one after this may carry me into my boys’ adolescence, and even with my good ability to imagine, it is indeed hard to imagine that chapter of muscle and grit; of my babies outgrowing me; of skinny, silly girls usurping my place as favorite female. Even harder to imagine are the books beyond the era when my children are no longer at home.

I see now that with my second book, I was not only learning how to be a mother and write fiction—I was learning how to be a mother and write at all. Doing both required a sudden shift in gears, a pushing through a deep level of exhaustion that ultimately provided stimulation and meaning for me in those early years of parenting. As soon as the kids were settled, I wrote. The windows were often short and punctuated by interruptions. They still are, though less so. I’m writing the new book almost strictly during the early hours of the day—thirty to sixty-minute intervals, mostly—before the boys are supposed to be awake. Inevitably, they come down early: asking for food, climbing onto my lap, squinting at the screen.

Sometimes I consider the fact that one morning, I’ll sit down with my laptop, the whole day stretching ahead of me. There will be no footsteps thundering overhead, no howling for breakfast. No one disrupting, no one needing. How delicious it seems, how out of reach. And yet I have to wonder: will I have to relearn how to write yet again? Without the pressure of such tight time constraints, without the urgency, will I be able to concentrate, produce, create? It’s hard to say, but I feel almost certain that all that silence, all that time, will not be as beautiful as the idea of it is, right now. That strange, nostalgic part of me will long for an interruption, long to hear my name.

—

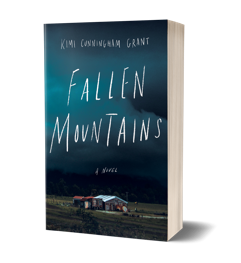

Kimi Cunningham Grant is the author of two books. Silver Like Dust is a memoir chronicling her Japanese-American grandparents and their internment during World War II. Her second book, Fallen Mountains, is a literary mystery set in a small town in Pennsylvania, where fracking has just begun. It will be released in March, 2019. Kimi is a two-time winner of a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Memorial Prize in Poetry and a recipient of a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts fellowship in creative nonfiction. Her poems and essays have appeared in Literary Mama, RATTLE, Poet Lore, and Whitefish Review. She studied English at Bucknell University, Messiah College, and Oxford University. She lives, writes, and teaches in Pennsylvania.

Follow her on Twitter @kimicgrant

Find out more about her on her website https://www.kimicunninghamgrant.com/

About FALLEN MOUNTAINS

When Transom Shultz goes missing shortly after returning to his tightly knit hometown of Fallen Mountains, Pennsylvania, his secrets are not the only ones that threaten to emerge.

When Transom Shultz goes missing shortly after returning to his tightly knit hometown of Fallen Mountains, Pennsylvania, his secrets are not the only ones that threaten to emerge.

Something terrible happened seventeen years ago. Red, the sheriff, is haunted by it. Possum, the victim of that crime, wants revenge. Chase, a former friend of Transoms, is devastated by his treacherous land dealings. And Laney worries her one thoughtless mistake with Transom could shatter everything shes built.

As the search for Transom heats up and the inhabitants dark and tangled histories unfold, each must decide whether to live under the brutal weight of the past or try to move beyond it. In Fallen Mountains, even loyalty, love, trust, and family can trap you on a path of tragedy.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing