Living With Your Characters

I was lucky enough to meet the legendary Iris Murdoch, years ago. I was one away from her at a dinner table and when the man between us left for a moment, and being in the early stages of a first novel, I leaned over to ask if she could possibly give me any tiny grain of advice.

I was lucky enough to meet the legendary Iris Murdoch, years ago. I was one away from her at a dinner table and when the man between us left for a moment, and being in the early stages of a first novel, I leaned over to ask if she could possibly give me any tiny grain of advice.

‘Know your characters,’ she said, ‘live with them, it’s all about character, nothing else.’ I stumbled out my thanks, thrilled to be given the time of day, and couldn’t wait to be back at my desk. I was soon far more acutely and absorbingly involved than I could have imagined. Having thought I’d done quite well in those few amateur chapters, the more I lived with my fledgling characters, consciously probing and discovering greater depths, their lapses of judgement, foibles; the back history that affected any inexplicable actions of theirs, the more clearly I realised how little I’d really known.

Living with them, dissecting their pasts, sharing their problems and agonies, I could describe them infinitely more fully than before. And trite and fey as it may sound, they became part of the family, discussed at meals as intimates, whether lovers, criminals or troubled souls. The more time I gave to them and lived in their skins, the more I knew how they’d think and speak, what they’d do in certain situations and which way they’d turn.

I’d come to fiction late in life and had to learn the hard way, on a very steep curve. I’d written and rewritten those few early chapters more times than I dare to admit and excitedly sent them off to a couple of publishers. It was the rejection slips – as well as Iris Murdoch – that made me revisit my work and see it with fresh eyes. Writing a first novel as an amateur oldster was, I slowly discovered, all about persevering and never losing faith. If I can write a novel, six of them to date, which still seems a miracle, then anyone can.

I never changed the storyline or characters, ploughing on with that first novel; they’d become too much a part of me, I discussed their strengths, indecisions and conundrums with my husband almost daily. I was helped by the fact that, never previously known for his patience, he was prepared to read the book, chapter by chapter. It took several goes – and publishers – but I got there. And all I’d changed was the style. The added polish came with time and the greater ‘layering’ of the many facets of the characters, their homes, jobs, failures and passions. My husband still reads my books and gets to know the new characters as well as the old; I’ve carried on some of them, it was just too hard to let go.

What about plot, you might ask, suspense, crime, thrillers, surely isn’t always all about character? Surely a story needs more? But it’s the emotions and instincts, the very makeup of the people who inhabit the story that create the plot. They dictate what happens, how it develops; a novel unfolds through the actions the characters take, slip-ups they make. You’ve put them in a particular situation, true, but you must then let them take you by the hand and lead you down unexpected paths.

You need an outline, the bones of a story, to show an agent or publisher, but from my experience, once you’ve been given the go-ahead, an editor will understand, even expect your story to deviate from the outline a little and go off-piste.

Some of the best novels are simply about getting through life, love and loneliness – the sort that can envelope and overcome you even when busy, working, surrounded by friends – and those brilliant pieces of writing have to depend on knowing with complete conviction what is going on inside the character’s head. Stories can be thrillers, a test of how good the writer is at jigsaws since the plot does need to fit together by the end, and they must have plenty of tension and suspense too, of course, but a thriller is all the richer for the roundedness of the characters who carry the plot.

Albert Camus said, ‘You can’t create experience, you undergo it,’ and it’s the same with writing; living and undergoing your characters’ lives is the key.

—

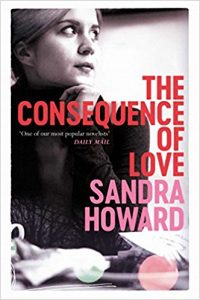

Sandra Howard was one of the leading photographic fashion models of the 1960s and 70s. She began doing freelance journalism while still modelling and continues to write for the press alongside writing novels. Her six published titles are Glass Houses, Ursula’s Story, A Matter of Loyalty and Ex-Wives. Sandra’s fifth novel, ‘Tell the Girl’ while not an autobiography, draws heavily on personal experiences of the 60s. Her sixth, The Consequence of Love, is a ‘stand alone’ sequel to A Matter of Loyalty.

Twitter: @howardsandrac

https://www.facebook.com/sandra.howard.7165

The Consequence of Love… is about the dilemmas of the human heart and the sacrifices made. Nattie is happily married to Hugo, they have two beautiful young children, but she has never known what happened to the man she truly loved. She still can’t let go; there has been no closure and even seven years on she still aches and pines, wondering and fearing the worst.Not knowing means not being able to grieve, that was the cruelty of it, hanging onto fading hope. Then one day, out of the blue, a messages appears in her emails… “Hello Nattie, I’m in London, very much hoping we can meet…”

The Consequence of Love… is about the dilemmas of the human heart and the sacrifices made. Nattie is happily married to Hugo, they have two beautiful young children, but she has never known what happened to the man she truly loved. She still can’t let go; there has been no closure and even seven years on she still aches and pines, wondering and fearing the worst.Not knowing means not being able to grieve, that was the cruelty of it, hanging onto fading hope. Then one day, out of the blue, a messages appears in her emails… “Hello Nattie, I’m in London, very much hoping we can meet…”

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Thanks Carol, lovely of you to have read it! x

Sandra and I follow each other on Twitter…we pass the odd remark about writing, age and life. SO good to read this post!