Method Writing: When Imagining Just Isn’t Enough

I sat at my computer, poking myself in the throat. Not the throat exactly, but the soft pucker just above the sternum, a place called the jugular notch. As I tapped, the muscle below my ribcage tingled queasily and bile fizzled up my throat. I wrote:

He doubled over, feeling as if he’d swallowed a block, then forced himself back up, pulling long funnels of steadying air through his nose, eyes watering, legs slightly rickety, a sharp acidity billowing in his chest.

Then I had to lie down until the feeling passed. For the rest of the day, it felt as if I had a small rubber ball trapped in my windpipe. I’d had no idea that the oddly strangled feeling would linger for so long. That too went into the book.

Then I had to lie down until the feeling passed. For the rest of the day, it felt as if I had a small rubber ball trapped in my windpipe. I’d had no idea that the oddly strangled feeling would linger for so long. That too went into the book.

Welcome to method writing.

Maybe it was my 15 years of being a journalist that made me determined to try to get everything accurate in my novel. But not just what color the tulips in Stuyvesant Square were in 2014 or how a neurologist would treat a rapidly growing aneurysm, but what a character’s body might feel like under certain circumstances.

Before I had a character down a shot of hard liquor, I went to my friend’s house, where he poured me a shot of tequila – something I hadn’t touched since college – so I could accurately describe the sensations it triggered in my nose, throat, and gut. Ah ha, the fumes exploded behind the eyes! Into the manuscript it went.

I also wanted to know if certain things my characters did were really possible.

When my female MC drugs my male MC and drags him across the floor to handcuff him to a stairway banister post, I wasn’t going to just write it. Oh sure, I could say she dragged him. This was fiction, after all. But could she really drag him?

My female MC was written as small. My male MC was written as tall, muscular, “built like a boxer.” Could a small female successfully drag a heavy man?

Next thing I knew, I was in my military vet neighbor’s apartment. He is also a writer, so he tolerated my madness. “Get on the floor!” I directed. “Go completely limp. You are drugged.”

“Pull me by the -”

“Don’t tell me! She wouldn’t know how to do it!”

Not surprisingly, I couldn’t drag him two inches. I cast around for a solution, yanked the comforter off his bed, then spread it next to him and managed to roll him most of the way on top of it. I was then able to pull the blanket, him along with it, across the floor. What I hadn’t expected is how my spine burned and my skin flushed hot and moist. Into the novel all it went.

But I probably hit my nadir as I sat there poking myself in the throat.

My male character is attacking a woman, trying to kill her. But she knows self-defense and isn’t going to be taken down that easily. After my military vet neighbor told me the best way to get a man off you would be to poke him in the jugular, I needed to know exactly how that felt, as part of the scene is told from the attacker’s POV.

Of course, I could imagine it. I could write that his throat burned, or it throbbed, or it closed up. But I wouldn’t really know. I should know. To me, it made all the difference in the world.

Method writing has probably colored my reading. I recently read a novel where two characters carry a wheelbarrow over mounds of fresh snow whilst simultaneously covering up their footprints with branches. All I could think was, how could they actually do this? How?

Unfortunately, there were many things in the book I couldn’t experience first hand. I couldn’t risk taking an overdose of sleeping pills, as one character does. Nor could I bring myself to call 911 in a suicide attempt so I could be checked into a psych ward. For that, I relied on interviews. And of course committing murder would be going a tad too far for my art. Instead, I listened to videos of murder confessions – YouTube is a research goldmine.

As for dialogue, I was determined to get that right too. When I had my MC tell her mother she was going to be getting married to her boss, whom she’d known for only a few months, I wasn’t sure what a mother would say under those circumstances – would she be thrilled, confused, disappointed? All three? I put out a call on Facebook for an older mother who had a close relationship with a 20-something daughter.

When I found a mom willing to play along, I told her the scenario. I’m your daughter, I’m going to phone you and give you some news. Call me by your daughter’s name, pretend I’m her, and react naturally.

Her rising hysteria and barbed inquisition at “my” sudden marriage plans caught me by surprise. Into the book her dialogue went, almost word for word. She later said it shocked her how genuine her reaction was despite knowing we were playing a game – and that it helped that my voice sounded like her daughter’s.

While I felt method writing added credibility to the novel, reading fiction is such a subjective experience. One of the first people who read the full manuscript noted that the mother’s dialogue sounded “rather unbelievable.”

That wasn’t entirely unusual. Life is often a series of stranger than fictions. Can’t you hear an editor chiding you that your Donald Trump character is flagrantly over-the-top and, frankly, “rather unbelievable”?

I think of the scene I wrote where my female MC learns some fantastically disturbing news. Having once lived through a similar emotional bomb, my real life reaction – a quick burst of inane laughter – was too surreal even for fiction and thus couldn’t be hijacked. (I have no doubt that if I’m brought in for questioning about a murder, I will smirk and giggle, ensuring my spot as number one suspect.)

At its core, method writing is a quest for the truth. But sometimes truth is too far fetched and imagination is the finer tool through which truth can be teased out in more digestible form.

—

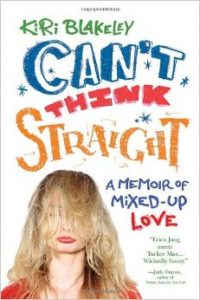

Kiri Blakeley is a longtime journalist who writes for The Daily Mail, and was a former Forbes reporter. She has written for The Stir, The Huffington Post, The New York Post, Marie Claire, She Knows, and many other outlets.

Kiri Blakeley is a longtime journalist who writes for The Daily Mail, and was a former Forbes reporter. She has written for The Stir, The Huffington Post, The New York Post, Marie Claire, She Knows, and many other outlets.

Her memoir, Can’t Think Straight: A Memoir of Mixed-Up Love about finding out her fiancé was secretly gay was called “A touching, delicious, compulsively readable account of life after love” by Kirkus Reviews. The book was featured on The Today Show, 20/20, Inside Edition and many other outlets.

She is a graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism. She just finished her first novel, about a reporter who discovers the philanthropist she loves might have a very dark past. She is a fan of gothic fiction and classic noir films. She lives in Brooklyn, where none of her writer friends used to live, but now they all do, so it’s kinda cliché to live here.

Twitter: @KiriBlakeley

Facebook: Writings of Kiri Blakeley

Buy Can’t Think Straight Here

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

I enjoyed this. Takes me back to my first novel and how I laid on the stairs upside down to try to figure out how my heroine might land. And, hey, you never know when you might need to punch some guy in the jugular!